|

| Greek god Hades, Morgantina Italy about 400 - 300 B.C. Terracotta and polychromy 10 ¾ x 8 1/16 x 7 5/16 in |

After nearly three years of back and forth, sometimes heated, oftentimes complicated due to regional Italian politics, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu is finally set to return a terracotta head depicting the Greek god Hades. The object had been irrefutably determined to have been clandestinely excavated, most likely from the Morgantina sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone in the Province of Enna, Sicily in 1978.

According to the Getty's website, the statue head was acquired between 1982 - 1985. By chance or luck, the Hades head matched a small fragment left behind in the Sicilian dirt: a little curly spiral painted with strokes of the same bright Egyptian blue as appears on the head's beard. Most likely the curl detached from the head's beard while being looted from the sanctuary, were it was found by the archaeological team just after discovering the illicit digging.

The bust was purchased by the museum for $530,000 from New York collector Maurice Tempelsman who had, in turn, purchased the object from British art dealer Robin Symes. For three decades prior to his death, Symes was once one of London’s most successful antiques dealers. Both Tempelsman and Symes are both known to have been conduits for tainted objects, laundered via local fences and high level antiquities dealers through to wealthy collectors or museums who then seemingly willingly purchased the illicit antiquities with limited or no collection history when building antiquities collections.

In a ceremony held in California at the John Paul Getty Museum, in the presence of Antonio Verde, the Consul General of Italy in Los Angeles, Francesco Rio, the Chief Prosecutor for the Italian state and Major Luigi Mancuso of the Italian Carabinieri's Art Crimes Squad, the USA museum formally relinquished the ancient object which dates back to 400-300 BCE.

|

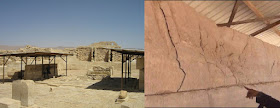

| The sanctuary of Persephone and Demeter at the ruins of Morgantina, just outside Aidone. |

The province of Enna contains more than two hundred registered and surveyed archaeological sites in addition to a high number of places known only to the area's tombaroli (illegal diggers). Spoken about in the writings of Cicero, Claudianus, Diodorus Siculo, and Livy, the ancient remains of the place give strong testimony to the vibrant life of the ancient populations of the island of Sicily, from the beginnings of the island's habitation through the great migrations of the Paleolithic epoch, up through the Middle Ages.

Of the ancient artworks recovered by the Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, nearly two out of three are reported to have come from this one Sicilian province. Few leave behind curly clues with which to identify objects as being looted.

References

Gill, D. W. J., and C. Chippindale. 2007. "From Malibu to Rome: further developments on the return of antiquities." International Journal of Cultural Property 14: 205-40.

Raffiotta, S. "Una divinità maschile per Morgantina." CSIG News. Newsletter of the Coroplastic Studies Interest Group, no. 11, Winter 2014, pp. 23-26.

Raffiotta, S. "Una divinità maschile per Morgantina." CSIG News. Newsletter of the Coroplastic Studies Interest Group, no. 11, Winter 2014, pp. 23-26.