Yesterday ARTnews broke a restitution story that a looted sculpture was in the process of being sent back home to Nepal, thanks to the help of the Art Institute of Chicago. The artefact, en route to Kathmandu, was referred to as a caturmukha linga, also sometimes called a Shivalinga or a Mukhalingam. Yet despite its differing names, these votary linga represent the Hindu god Shiva. In this instance, the object in question has four faces, each pointing toward a cardinal direction, evoking different aspects of the sacred deity.

According to the article's author, Alex Greenberger, Senior Editor at ARTnews, the museum declined to name the collector identified as the holder of the artwork. One of the oldest and largest art museums in the United States, the Art Institute of Chicago said only that the antiquity in question "had never been accessioned" into their collection.

The Illinois museum also did not provide clarification on the artefact's collection history or elaborate further on how they knew the idol was stolen, or when, or from where, the Shivalinga had been removed. All this empty space surrounding a restitution is indicative of formal or informal confidentiality agreements and sometimes these are the only means of ensuring a collector, or his or her heir(s), agree to relinquish an artefact voluntarily.

Underscoring this, an email, from the embassy of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal had only limited details and cited that an “agreement” had been reached between the object's holder and the embassy for the caturmukha linga's voluntarily surrender.

But to answer the question on every provenance researcher's mind, I've outlined what we have been able to determine, prefacing it that all this information is available in open-source records available to the public if you are willing to dig a bit deeper.

|

| Image Credit: POLYMath Design |

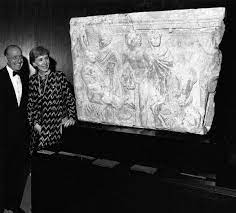

Over the years the Alsdorf donations significantly enriched the collections of North American Museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago. Their collection, before it was broken up, donated, or sold, was an example of cross-category collecting and encompassed antiquities, works on paper, European and Latin American art, and Indian and Southeast Asian and Asian art as well as paintings by Frida Kahlo, René Magritte, Joan Miró among others. Yet some of the objects the ancient art they collected have raised some questions as to whether or not the Alsdorfs conducted sufficient due diligence before purchasing pieces for their collection.

As a testament to their relationship with The Art Institute of Chicago, the Alsdorf's generosity made possible a Renzo Piano-designed renovation to the institution's Alsdorf Galleries for Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art. It is here where a considerable portion (approximately 400 objects) of the Alsdorf Collection is now viewable.

Outside Illinois, the couple's sway in the art and political world was no less influential. Mr. Aldsorf was appointed to the U.S. Information Agency's Cultural Affairs Committee, first by President Ronald Reagan and later by President George H. W. Bush. But back to our stolen artefact.

|

| The Pashupatinath Temple Complex |

No comments:

Post a Comment