|

| A man of many "pezzini" |

As mentioned in an earlier ARCA blog post this week, Matteo Messina Denaro, the former fugutive Cosa Nostra boss, was interrogated on February 13, 2023 for almost two hours at a maximum security prison in Italy. There, the crime boss fielded many questions, and sometimes duelled with Palermo prosecutor Maurizio De Lucia and deputy prosecutor Paolo Guido when their questions struck too close to home.

According to the official transcript of their exchange, which covers 69 printed pages and is marked in several places with the handwritten word “omissis”, (used to mark redactions in the interrogation), the Cosa Nostra boss, curated his words carefully. In many cases he only only incriminated himself verbally in specific areas where there was already overwhelming evidence of specific and proven actions. In other instances, he obliquely ignored questions he didn't want to answer, while seemingly going off on tangents, as if he wanted his say on key subjects to be memorialised so that others might read and interpret his statements later.

Speaking to the two magistrates, Messino Denaro again distanced himself from the murder of Giuseppe Di Matteo. Repeating what he had previously told investigating Judge Alfredo Montaldo, who had questioned him in relation to another trial in which he is accused of attempted extortion. The boss admitted to prosecutors De Lucia and Guido that he played a role in the 12 year old's kidnapping on November 23, 1993 and made it clear that seizing the child was a volley designed to coerce the father, Cosa Nostra informant Santino Di Matteo, into retracting statements given to the Anti-Mafia District Directorate (DDA) of Palermo.

Giuseppe was escorted out of horse stables in Villabate by four mafiosi dressed as policemen. His kidnappers had promised him that they were bringing him to see his father. Once under their control, the child was held hostage for a total of 779 days in various locations between the provinces of Palermo, Trapani, and Agrigento.

Ironically, at one point the boy was taken, hooded and locked in the trunk of a car, to a farmhouse in Campobello di Mazara, the same village where Messina Denaro was found to be hiding at the time of his January 16, 2023 capture. After years as a hostage, and increasingly becoming a liability to his captors, Giuseppe was strangled to death on January 11, 1996 in the Giambascio countryside outside Palermo. His body was then dissolved in acid.

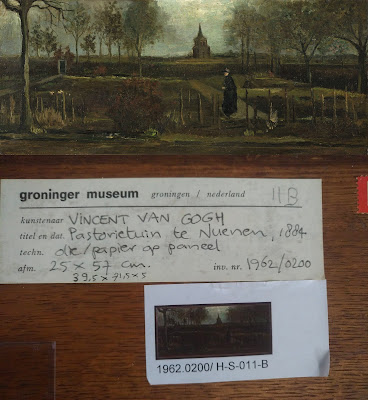

|

Matteo Messina Denaro was involved in the massacres of 1993,

including this one in Florence in via Georgofili |

In July of this year, the Caltanissetta court of appeal confirmed Matteo Messina Denaro's life sentence for his role in dozens of murders including Giuseppe's. The others include:

- The May 23, 1992 bombing which killed anti-Mafia magistrate Giovanni Falcone, his wife, and three officers of their police escort as their cars passed near the small town of Capaci;

- The July 19, 1992 bombing in Via Mariano D'Amelio (Palermo) which killed Judge Paolo Borsellino and five members of his security detail;

- The 1993 bombings carried out at art and religious sites in Milan, Florence and Rome that killed 10 people and injured 40 others:

During his interrogation Matteo Messina Denaro denied being involved in the trafficking in drugs, but openly admitted to prosecutors other things they already knew and had confirmed, such as having regularly passed pizzinu (small piece of paper, containing sometimes coded messages) with convicted Cosa Nostra “boss of bosses” Bernardo Provenzano, who once headed the Mafia's powerful Clan dei Corleonesi.

In these messages, sent while both men were already fugitives from justice, Messina Denaro admitted that the pair asked one another for favours, but his admission of his relation with Provenzano during this interrogation wasn't revelatory. Investigators already had undeniable proof of the pair's communication in the form of ten pizzini, sent between 2003 and 2006, which agents had recovered in Provenzano's hideout when he was captured in Montagna dei Cavalli near Corleone on April 11, 2006.

|

| The Farm Hideout of Bernardo Provenzano |

One of those messages is practically a testament of fealty by Messina Denaro to Provenzano and spoke with deference to the crime boss saying:

"Lei è sempre nel mio cuore e nei miei pensieri, se ha bisogno di qualcosa da me è superfluo dire che sono a sua completa disposizione e sempre lo sarò. La prego di stare sempre molto attento, le voglio troppo bene".

In another, writing as his nephew "Alessio," Messina Denaro wrote to his Uncle Bernardo saying:

"I know the rules and I respect them, the proof that I know the rules and that I'm respecting lies precisely in the fact that I'm turning to you to fix this unpleasant affair, this for me is respecting the rules. You tells me that money in life isn't everything and that there are good things that money doesn't can buy. I totally agree with you, because I have always thought that one can be a man without a lira and one can be full of money and be mud."

Offering both a mundane and fascinating image of himself on the lam, a substantial part of the Corleonese godfather's interrogation statements focus on the time period in his life immediately leading up to his capture. Perhaps because by this period he understood that the clock was ticking and understanding that a) he couldn't hide forever and b) he needed help from others given his declining health.

Some of his statements appear to be attempts to exonerate some of those individuals, who have been arrested on suspicion of having helped the Cosa Nostra boss during his illness, including statements in defence of Doctor Alfonso Tumbarello, whom Messina Denaro told the magistrates:

"knows nothing."

Other individuals close to the boos faired less well during the Messina Denaro's ramblings.

When speaking about undergoing medical care in Palermo under the false name of Andrea Bonafede, as an outpatient at the multi-specilaity hospital La Maddalena, Messina Denaro described several of the steps he needed in order to obtain false identity documents, knowing that he could not undergo chemotherapy and medical treatment in the state's medical institution directly under his own name.

In this part of the interview Messina Denaro stated:

"I had a friendship with Andrea Bonafede, but a remote friendship because his father worked for us, for my father and then my father was a friend of his uncle, he had a another uncle suspected mafia convicted of mafia".

Investigators contend that in addition to lending his name, Bonafede received 20,000 euros from the Matteo Messina Denaro to buy a house in western Sicily that would serve as one of the fugitive's hideouts.

Messina Denaro also told the magistrates about a second assumed identity, used in the city of Campobello di Mazara, the Sicilian town that sheltered him. Here he was known under the pseudonym “Francesco”, a Palermitan man who purportedly relocated from the city to the smaller town while caring for his ailing mother and two elderly aunts.

Living dual identities while hiding in plain site within the Campobello community, Messina Denaro also admitted that in addition to travelling back and forth to the Palermo hospital for treatment, either alone or with an escort, he had openly visited Campobello's bakeries, greengrocers, and supermarkets. He also played poker and eat in local restaurants. Again, nothing extremely revelatory, as receipts and objects found in his hiding places confirm some of the his admitted activities.

What is more of interest to readers of ARCA's Art Crime blog were the from-the-horse's-mouth affirmations made during this hour and forty minute interrogation that confirm directly from the source that Matteo Messina Denaro's family, and that of his father, Francesco Messina Denaro, capo mandamento in Castelvetrano and head of the mafia commission of the Trapani region, sustained their livelihoods, to some extent, by the proceeds of antiquities crimes.

Messina Denaro's verbal admissions concretise a written statement previously attributed to him, which was already mentioned in an article published in 2009 by Rino Giacalone for Antimafia Duemila. In that article, the journalist refers to an intercepted "pizzini" written by Messina Denaro where the crime boss wrote almost word for word, what he admitted to during this interrogation.

"With the trafficking of works of art we support our family."

Francesco Messina Denaro as readers of ARCA's blog may recall was already believed to have been behind the theft of the famous Efebo of Selinunte, a 5th century BCE statue of Dionysius Iachos, stolen on October 30, 1962 and recovered in 1968 through the help of Rodolfo Siviero.

Matteo Messina Denaro was verbose when speaking to his dead father's and the family's involvement in the illicit antiquities trade. He also mentions that his family bought from everyone and laundered antiquities illegally removed from Sicily via Switzerland, in an enterprise which supporting some 30 members of his family, including some who were incarcerated and others like himself who were on the run. But the boss was far more laconic when asked directly if he knew Castelvetrano ancient art dealer Gianfranco Becchina. In response to the PM's query in this regard, he answered:

"lo conosco perché è un paesano mio, a prescindere, anche senza i beni... i pezzi archeologici, lo conosco lo stesso, perché siamo paesani."

In October 2018, following a formal request by the Deputy Prosecutor for the District Anti-Mafia Directorate Carlo Marzella, preliminary reexamination judge of of the Court of Palermo, Antonella Consiglio, dismissed the charge of mafia association against Becchina citing in her decision that the accusations used for the basis of the charge, made originally via testimonies given by verbose mafia defector Vincenzo Calcara, had been deemed "unreliable".

Back in 1992, Calcara, and now deceased former drug dealer Rosario Spatola, incriminated Gianfranco Becchina for alleged association with the Campobello di Mazara and Castelvetrano clans, implying that there was a gang affiliate active in Switzerland whose role it was to sell ancient artefacts originating from the mab's black market. At the time of his testimony, much of Calcara's information was discounted as many were skeptical that he had actual knowledge of the facts he represented or whether he invented things for his own benefit.

Matteo Messina Denaro's statements during his February interrogation however confirm that a network of criminals funnelled numerous illicit antiquities from Sicily through the art market in Switzerland, which flowed onward, into world museums. But the mafia boss stopped short however, on confirming, by name, whose hands, these works of ancient art passed through.

Like Provenzano before him, Matteo Messina Denaro, at least for now, seems to be determined to be his own custodian of many secrets, especially those which might openly implicate living individuals, who have direct or indirect relationships with the Cosa boss and result in their arrest and/or convictions. Facing a terminal illness, Messina Denaro's statements are well-guarded, and for the most part his scant confessions during the interrogation seem wholly performative.

Like so many mobsters before him, it seems that he plans to carry most of the Cosa Nostra's bloody business dealings with him to his grave.

By: Lynda Albertson

antiquities looting,Facebook,Thailand

antiquities looting,Facebook,Thailand

No comments

No comments

.png)