Antiquities trafficking continues to make headlines in multiple countries in 2015. In this last of a three part series, ARCA explores one final art trafficking network that underscores that the ownership and commodification of the past continues long after the traffickers have been identified.

August 31, 1995

|

| Europa Paestan red-figure Asteas signed calyx-krater |

In a fluke summer accident, Pasquale Camera, a former captain of the Guardia di Finanza turned middle-man art dealer, lost control of his car on Italy’s Autostrada del Sole, Italy's north-south motorway, as he approached the exit for Cassino, a small town an hour and a half south of Rome. Smashing into a guardrail and flipping his Renault on its roof, Camera’s automobile accident not only ended his life but set into motion a chain reaction that resulted in a major law enforcement breakthrough that disrupted one of Italy’s largest antiquities trafficking networks.

While the fatal traffic accident fell under the jurisdiction of Italy’s Polizia Stradale, the Commander of the Carabinieri in Cassino was also called to the scene. The investigating officers had found numerous photographs in Camera's vehicle which substantiated what investigators had already suspected, that the objects depicted in the photos had been illegally-excavated and that Camera had been actively dealing in looted antiquities.

|

| Tombarolo holding Asteas signed calyx-krater |

The images in the car were of a hodgepodge of ancient art. Two that stood out in particular were of a statue in the image of Artemis against the backdrop of home furnishings and a Paestan red-figure calyx-krater, signed by Asteas in what looked to be someone's garage.

Having been previously assigned to the Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, the Commander from Cassino called the TPC’s Division General, Roberto Conforti, who requested a warrant be issued to search the premises of Camera’s apartment in Rome, near Piazza Bologna.

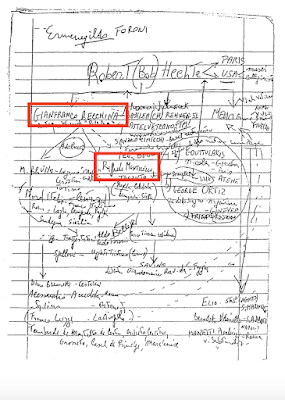

Investigators who carried out the search of

Pasquale Camera's personal possessions discovered hundreds of photographs, fake and genuine antiquities, reams of documentation and the now famous Medici organagram. This org chart revealed Giacomo Medici’s central position in the organization of the antiquities trade out of Italy. Interestingly, the wallpaper in Cameria's apartment also matched the background of the photo of the

Artemide Marciante found in Camera's vehicle.

Subsistance Looter to Middle Man

Another photo, of Antimo Cacciapuoti, showed the tombarolo holding the freshly-looted Asteas-signed Europa krater. A copy of this photo was provided by

journalist Fabio Isman for the purpose of this article. Isman confirmed that this image was one of the Polaroids found in Camera's Renault and went on to add that during later negotiations Cacciapuoti would confess to having been paid 1 million lire plus "a suckling pig" for his work in supplying the krater.

One of the links in Italy's largest known trafficking chain had begun to crack.

|

| Medici Organagram |

As the investigation progressed authorities went on to raid Giacomo Medici’s warehouse at the Geneva Freeport in September 1995 and recovered 3,800 objects and another 4,000 photographs of ancient art that had, at one time or another, passed through Medici’s network.

1998 Identifications

Matching seized photos to looted works of art is a laborious process. Three years after the start of the investigation Daniela Rizzo and Maurizio Pellegrini from the

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell'Etruria meridionale at the

Villa Giulia, working with the

Procura della Repubblica (the state prosecutor's office) and the Court of Rome on this case, identified the Artemide Marciante from the photo found at the scene of Camera's fatal auto accident. The photo of the statue matched another found in a June 1998 issue of House and Garden Magazine and another photo seized from Giacomo Medici which showed the object unrestored and with dirt still on it. This statue was ultimately recovered from Frieda Tchacos.

Rizzo and Pellegrini also identified the location of the Paestan red-figure calyx krater, painted and signed by Asteas. It had been sold by the dealer Gianfranco Becchina to the John Paul Getty Museum in 1981.

2001-2005 More Seizures

2001-2005 More Seizures

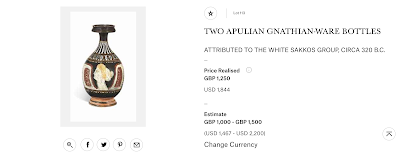

In the early years of the new century law enforcement authorities investigating this trafficking cell widened their attention on Gianfranco Becchina, whose name was listed on the organagram, placing him as head of a cordata and as a primary supplier to Robert Hecht. This important lead convinced investigators to explore Becchina's suspected involvement in this trafficking cell.

As the investigation continued authorities seized 140 binders containing 13,000 more documents, 8,000 additional photographs of suspect objects and 6,315 artworks from Becchina's storage facilities and gallery.

Instead, this article focuses on what is happening in the present and serves to demonstrate that despite the nearly two decades that have past since Pasquale Camera's car veered off Italy's

A-1 autostrada, suspect illicit antiquities, traceable to this network, continue to be sold, often openly, on the lucrative licit art market.

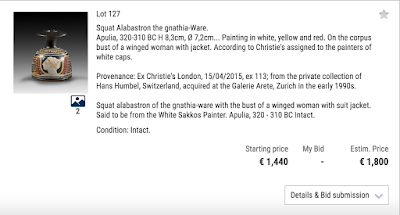

To underscore the conundrum of

looted to legitimate Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis a Research Assistant with the Trafficking Culture Project, housed in the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at the University of Glasgow has highlighted four objects for sale at Christie’s upcoming antiquities auction in London, on Wednesday, 15 April 2015. For the last eight years (2007-present), Tsirogiannis has been

identifying looted and ‘toxic’ antiquities as they come up for sale from photographic

evidence he was given by authorities from the three primary dossiers of photographs derived from the property seizures in these cases.

Each of these four objects listed below have been identified by Tsirogiannis as having corresponding photos in these archives, something potential purchasers may want to consider when bidding on antiquities that, at face value, are reported to have legitimate collection histories.

SALE 10372 Lot 83 Property of a Gentlemen

SALE 10372 Lot 83 Property of a Gentlemen

Provenance: Private collection, Japan, acquired prior to 1980s.

Anonymous sale; Christies, New York, 12 December 2002, lot 16.

Private collection, New York, acquired at the above sale with

Charles Ede Ltd, London, from whom acquired by the present owner in 2006.

Beazley archive no. 26090.

At first blush, review of Christie's sales notes on these objects seems to demonstrate a modicum of collecting history pedigree which normally would serve to comfort potential buyers. None of the auction lot however go on to reveal where these objects were found, or whether their excavation and exportation from their country of origin were legal.

This should be the first alarm bell to any informed collector considering a purchase on the licit antiquities market. ARCA reminds its readers and buyers of art works that lack of this information in an object's collection history should be a strong signal that the object may be suspect and that it is better to walk away from a beautiful antiquity than purchase an object that quite possibly may have been looted or illegally exported.

Extracts from Notes by Dr. Tsirogiannis on the Christie's Auction Lots

Regarding Lot 83

Christie's catalogue does not include any collecting history of this

Greek amphora before its appearance in Japan in the 1980's.

Documentation in the Becchina archive links Becchina to three German

professors regarding the examination of the amphora in the 1970's.

Regarding Lot 102

From Watson's and Todeschini's book, we know that in the 1980's Medici used to consign antiquities to Sotheby's in London, through various companies and individuals. Why does the Christies auction not include any collecting history before the 1985 Sotheby's auction.

Regarding Lot 108

Again, Christie's advertise their due diligence, but the catalogue does not include any collecting history of this antiquity before the 1986 Sotheby's auction.

Regarding Lot 113

Again, Christie's advertise their due diligence, but the catalogue is not precise about the collecting history of this antiquity prior to 1998.

Are these Notifications Helpful?

In the past, when Dr. Tsirogiannis or

Dr. David Gill have pointed out objects with tainted collection histories, dealer association members and private collectors have countered by screaming foul. They have asked,

Others have criticized this practice saying that by outing sellers and auction houses on their tainted inventory, the objects simply get pulled from auction and proceed underground. Detractors believe that this leaves dealers to trade illicit objects in more discreet circles, where screenshots and image capture are less accessible to investigators and researchers and where the change of hands from one collector to another adds a future layer of authenticity, especially where private collections in remote location buyers are less likely to be questioned.

I would counter these concerns by saying that researchers working on this case diligently work to not impede ongoing investigations by the Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale and Italy's Procura della Repubblica and to notify the appropriate legal authorities in the countries where these auctions take place. In the case of these four antiquities INTERPOL, the Metropolitan Police and the Italian Carabinieri have been notified.

But police officers and dedicated researchers only have so many sets of eyes and the prosecution of art crime requires dedicated investigators and court hours not often available to the degree to which this complex problem warrants. To mitigate that, it is time that we dedicate more time educating the opposite end of the looting food chain; the buyer.

The academic community needs to learn to apply persuasive, not adversarial, pressure on the end customer; the buyers and custodians of objects from our collective past. By helping buyers become better-informed and conscientious collectors we can encourage them to demand that the pieces they collect have thorough collection histories or will not be purchased. As discerning buyers become more selective, dealers will need to change their intentionally blind-eye practice of passing off suspect antiquities with one or two lines of legitimate buyers attached to them.

Buyers would also be wise to apply the same pressure to auction houses that they apply to dealers, persuading them to adopt more stringent policies on accepting consignments. Auction houses in turn should inform consignors that before accepting items for consignment that have limited collection histories they will be voluntarily checking with authorities to see if these objects appear in these suspect photo dossiers. In this way the legitimate art market would avoid the circular drama of having their auctions blemished with reports of trafficked items going up for sale to unsuspecting buyers or to having gaps in their auction schedule when auction houses are forced to withdraw items on the eve of an upcoming sale.

In April 2014

James Ede, owner of a leading London-based gallery in the field of Ancient Art and board member of the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art wrote an article in defense of the antiquities trade in Apollo Magazine where he stated:

The

IADAA's Code of Ethics states: "The members of IADAA undertake not to purchase or sell objects until they have established to the best of their ability that such objects were not stolen from excavations, architectural monuments, public institutions or private property."

In the past Mr. Ede has stated

that small dealers couldn't afford to use private stolen art databases such as those at the

Art Loss Register. I would ask Mr. Ede in the alternative how many London dealers registered with the IADAA have ever picked up

the phone and asked Scotland Yard's art squad to check with INTERPOL or

their Italian law enforcement colleagues when accepting a consignment where the collecting histories of an object deserved a little more scrutiny?

Or better still, should the more than 14,000 photos of objects from these dossiers ever be released, to private stolen art databases or to a wider public audience, how would the IADAA ensure that its membership actually cross-examine the entire archival record before signing off that the object is not tainted? Mr. Ede has also indicated previously that the IADAA only requires its

members to do checks on objects worth more than £2000. Items of lessor

value would take too much time or prove too costly to the dealers.

In 2015 is it correct for dealers to remain this passive and wait for law enforcement to tell them something is afoot? Would the general public accept such an attitude from used car sellers regarding stolen cars?

Given that Mr. Ede is the former chairman and board member since the founding of the IADAA, an adviser of the British Government, a valuer for the Portable Antiquities Scheme, and a member of the council of the British Art Market Federation his thoughts on this matter carry considerable weight in the UK. As such he is scheduled to speak

on April 14, 2015 at the Victoria and Albert Museum on "The Plunder: Getting a global audience involved in the story of stolen antiquities from Iraq and Syria."

I am curious how Professor Maamoun Abdulkarim, Director General Art and Museums, Syria who is also speaking at this event would feel about low valued items being excluded from the IADAA's "clean or tainted" cross checks or if Mr. Ede has any workable suggestions that would actually begin to address this problem in an active, rather than passive way among the art dealing community.

Will blood antiquities be held to a higher standard of evaluation given the public's interest while it remains business as usual for objects looted from source countries not involved in civil war or conflict?

By Lynda Albertson

References Used in This Article

Antoniutti, A., and C. Spada. "Fabio Isman, I predatori dell'arte perduta. Il saccheggio dell'archeologia in Italia." Economia della Cultura 19.2 (2009): 301-301.

Felch, Jason, and Ralph Frammolino. "Chasing Aphrodite. The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum." (2001).

Marconi, Clemente, ed. Greek

Vases: Images, Contexts and Controversies; Proceedings of the

Conference Sponsored by The Center for the Ancient Mediterranean at

Columbia University, 23-24 March 2002. Vol. 25. Brill, 2004.

Watson, Peter, and Cecilia Todeschini. "The Medici Conspiracy: Organized Crime, Looted Antiquities, Rogue Museums." (2006).

Auction Alert,Becchina,Becchina archive,Bonhams,Christie's,Christos Tsirogiannis,giacomo medici

Auction Alert,Becchina,Becchina archive,Bonhams,Christie's,Christos Tsirogiannis,giacomo medici

No comments

No comments