|

| Image Credit - HSI - ICE |

On 21 February 2006 the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Italian government signed an agreement under which the Met agreed to return 21artefacts looted from archaeological sites within Italy's borders. With that accord, the New York museum yielded its prized sixth-century BC "hot pot," a Greek vase known as the Euphronios krater. As part of that historic accord, the museum also relinquished a red-figured Attic amphora by the Berlin Painter; a red-figured Apulian Dinos attributed to the so-called Darius Painter; a psykter with horsemen; a Laconian kylix, and 16 rare Hellenistic silver pieces experts determined were illegally excavated from Morgantina in Sicilia. It also included a carefully-worded clause which stated:

I) The Museum in rejecting any accusation that it had knowledge of the alleged illegal provenance in Italian territory of the assets claimed by Italy, has resolved to transfer the Requested Items in the context of this Agreement. This decision does not constitute any acknowledgement on the part of the Museum of any type of civil, administrative or criminal liability for the original acquisition or holding of the Requested Items. The Ministry and the Commission for Cultural Assets of the Region of Sicily, in consequence of this Agreement, waives any legal action on the grounds of said categories of liability in relation to the Requested Items.

Admitting no wrongdoing, where there surely was some, this unprecedented and then-considered watershed resolution, put an end to a decades-old cultural property dispute, with both sides choosing the soft power weapon of collaboration and diplomacy, complete with agreed upon press releases that enabled Italy to get its stolen property back without the need for costly and sometimes fruitless litigation.

The signing of this 2006 agreement was thought to usher in a new spirit of cooperation between universal museums and source nations that those working in the field of cultural restitution hoped would permanently alter the balance of power in the international cultural property debate. At the time of its signing at the Italian cultural ministry, the Met's then-director, Philippe de Montebello, said the agreement "corrects the improprieties and errors committed in the past."

Heritage advocates applauded the agreement, hopeful that museums around the globe would begin to more proactively explore their own problematic accessions and apply stricter museum acquisition policies to prevent looted material from entering into museum collections. Coupled with collaborative loan agreements, museums and source country accords like this one, combined with strongly worded ethics advisories, like the one set forth that same year by the International Council of Museums in their ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums should have served to eliminate the bulk of problematic museum purchases and donations without the need for piece by piece requests for restitution and protracted and costly litigation.

But has it?

The aforementioned ICOM document clearly states:

4.5 Display of Unprovenanced Material

Museums should avoid displaying or otherwise using material of questionable origin or lacking provenance. They should be aware that such displays or usage can be seen to condone and contribute to the illicit trade in cultural property.

8.5 The Illicit Market

Members of the museum profession should not support the illicit traffic or market in natural or cultural property, directly or indirectly.

Yet, here we are, 16 years after that signing of the Met-Italy accord, with the same universal museum [still] hanging on to and displaying material of questionable origin, long after their questionable handlers have been proven suspect. Likewise, 16 years later, and with the persistence of the Antiquities Trafficking Unit at New York District Attorney's Office in Manhattan, we see another 21 objects being seized last month from the largest art museum in the Western Hemisphere.

In total, some 27 artefacts have been confiscated in the last year from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, In 2022 alone, five search warrants have resulted in seizures of pieces from within the museum's collection, demonstrating that the Met, and other universal museums like it, (i.e., the Musée du Louvre and the Louvre Abu Dhabi) have yet to satisfactorily master the concepts of “provenance” research and “due diligence”.

Founded in 1870, the MMA's mission statement states that it "collects, studies, conserves, and presents significant works of art across time and cultures in order to connect all people to creativity, knowledge, ideas, and one another." Yet, despite holding many problematic artefacts purchased, not only the distant past, but also in the recent, the Met still struggles with the practical steps it should be taking regarding object provenance and exercising due diligence, both before and after accessioning purchases and donated material into their collection.

As everyone [should] know by now, the concept of provenance refers to the history of a cultural object, from its creation to its final destination. Due diligence, on the other hand, refers to a behavioural obligation of vigilance on the part of the purchaser, or any person involved in the transfer of ownership of a cultural object, (i.e., museum curators, directors, legal advisors etc.,). This need for due diligence stretches beyond the search for the historical provenance of the object, but needs to also strive to establish whether or not an object has been stolen or illegally exported.

So while we applaud the Metropolitan Museum of Art for having been fully supportive of the Manhattan district attorney’s office investigations, as has been mentioned in relation to the August 2022 seizure, we would be remiss to not question why, in the last 16 years, and despite the fact that the “Met’s policies and procedures in this regard have been under constant review over the past 20 years,” the museum has still not addressed these problematic pieces head on.

This museum is home to more than two million objects. Despite the responsibility and gravitas required for building and caring for such a large collection of the world's cultural and artistic heritage, the Met has yet to establish a single dedicated position, with the requisite and necessary expertise, to proactively address the problematic pieces it has acquired in the past, and to serve as a set of much needed set of breaks, when evaluating future acquisitions, so that the next generation of identified traffickers, don't also profit from the museum's coffers as they did with the $3.95 million dollar golden coffin inscribed for Nedjemankh and five other Egyptian antiques worth over $3 million confiscated from the museum under a May 19 court order.

For the most part, provenance has been carried out haphazardly, and by only one or two people, working in specific departments, primarily in curatorial research rolls that only covering specific historical time frames or one or two material cultures. The lack of that comprehensive expertise brings us to apologetic press statements and a plethora of seizures like ones we have seen over the last year.

But moving on to what was seized at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on 13 July 2022. The $11 million worth of objects include:

a. A bronze plate dated ca. 550 BCE ,measuring 11.25 inches tall, and valued at $300,000.

This artefact was donated by Norbert Schimmel, a trustee at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who, during his tenure, was member of the Met's acquisitions committee. By 1982 he was known to be purchasing antiquities from Robin Symes via Xoilan Trading Inc., Geneva. This firm shared a Geneva warehouse address (No. 7 Avenue Krieg in Geneva) with two of Giacomo Medici’s companies, Gallerie Hydra and Edition Services.

Symes is noted as being one of the leading international merchants of clandestinely excavated archeology. His name appears in connection with four different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

b. A marble head of Athena, dated ca. 200 BCE, measuring 19 inches tall and valued at $3,000,000.

This Marble Head of Athena was with Robin Symes until 1991, then passing to Brian Aitken of Acanthus Gallery in 1992. It was then sold to collectors Morris J. and Camila Abensur Pinto, who in turn, loaned the artefact to the Met in 1995. It was then purchased by the Metropolitan in 1996.

Symes's name appears in connection with four different objects in this Met seizure, while Aitken's name comes up frequently as having bought from red flag dealers. His name appears in connection with two different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

c. A fragmentary terracotta neck-amphora, dated ca. 540 BCE, measuring 14.75 inches tall and valued at $350,000.

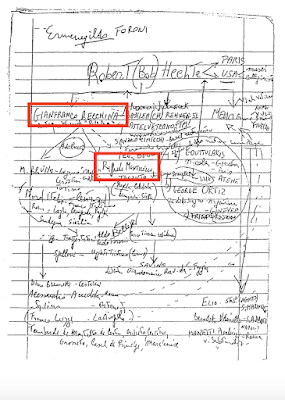

This fragmented neck-amphora was purchased by the Met from Robert Hecht (Atlantis Antiquities) in 1991. Four years later, Hecht's name would appear in seized evidence outlining his key position at the top of two trafficking cordata on a pyramid org chart which spelled out seventeen individuals involved in one interconnected illicit trafficking network.

Archaeological artefacts sold by Hecht have been traced to the collections of the Met, the British Museum, the Musee du Louvre, and numerous other U.S. and European institutions, many of which have been determined to have come from clandestine excavations.

Polaroids photographs of this artefact, shot after the advent of Polaroids in 1972, are among the seized materials found within the Giacomo Medici archive. These photos depict the neck-amphora balanced precariously on a rose-colored upholstered chair.

As mentioned above, Hecht's name appears in connection with three different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

d. A terracotta red-figure kylix, dated ca. 490 BCE, measuring 13 inches in diameter, and valued at $1,200,000.

This fragmented kylix was purchased from Frederique Marie Nussberger-Tchacos in 1988 and consolidated with other terracotta fragments purchased earlier from Robert Hecht in 1979.

In 2002 Tchacos was the subject of an Italian arrest warrant in connection with antiquities laundering. And again, as mentioned above, Hecht's name appears in connection with three different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

e. A marble head of a horned youth wearing a diadem, dated 300-100 BCE measuring 14 inches tall, and valued at $1,500,000.

This marble head of a horned youth wearing a diadem passed through the ancient art collection of Nobel Prize winner Kojiro Ishiguro, another client of Robin Symes. It was then purchased by Robert A. and Renee E. Belfer when sold by the Ishiguro family via Ariadne Galleries. Afterwards it was gifted by the Belfers to the Met in 2012.

__________

f. A gilded silver phiale, dated ca. 600-500 BCE, measuring 8 inches in diameter, and valued at $300,000.

This long-contested gilded silver phiale was purchased via Robert E. Hecht in 1994. As mentioned previously Hecht's name appears in connection with three different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

g. A glass situla (bucket) with silver handles, dated ca. 350-300 BCE, measuring 10.5 inches tall, and valued at $400,000.

This unique glass situla was purchased by the Met through Merrin Gallery in 2000. Photos and proof of sale of this artefact are documented in the archive of suspect dealer Gianfranco Becchina. Correspondence within in the Becchina Archive cache of business records shows communication between the Sicilian dealer and Ed Merrin and/or his gallery dating back to the 1980s. In the book, The Medici Conspiracy, by Peter Watson and Cecelia Todeschini, the writers cite one letter written by Merrin Gallery to Becchina, where Becchina was asked not to write his name on the back of photos of antiquities he sent for consideration.

Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure. Merrin Gallery appears in connection with multiple objects within this seizure.

_________

h. A terracotta lekythos, dated ca. 560-550 BCE, measuring 5.3 inches tall and valued at $20,000.

This terracotta lekythos was purchased from Galerie Antike Kunst Palladion in 1985 the same year Becchina sold a suspect krater by the Ixion painter to the Musée du Louvre.

As mentioned above, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

i. A terracotta mastos, dated ca. 520 BCE, measuring 5.5 inches in diameter and valued at $40,000.

Before he even moved to Switzerland, Gianfranco Becchina was already selling to the J. Paul Getty Museum in 1975. According to the Met's records, which we believe contain a date error, this terracotta nipple-shaped cup was purchased from Antike Kunst Palladion in 1975. However, records show that Becchina emigrated from Castelvetrano in Sicily to Basel, Switzerland after having undergone a bankruptcy procedure in 1976 and formed the Swiss business that same year.

As mentioned previously, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

j. A fragment of a black-figure terracotta plate, dated ca. 550 BCE, measuring 3 by 2.5 inches and valued at $4,000.

This fragment, attributed to Lydos, was purchased by the Metropolitan from Galerie Antike Kunst Palladion in 1985.

As mentioned above, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

k. A fragment of a black-figure terracotta amphora, dated ca. 530 BCE, measuring 2 by 2.6 inches and valued at $1,500.

This fragment, attributed to the Amasis Painter, was purchased from Galerie Antike Kunst Palladion in 1985.

As mentioned previously, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

1. A pair of Apulian gold cylinders, dated ca. 600-400 BCE, measuring 2.25 inches in diameter and valued at $10,000.

This pair of gold Apulian cylinders was gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1981 by Mr. and Mrs. Gianfranco Becchina.

As mentioned above, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

m. A bronze helmet of Corinthian type, dated 600-550 BCE, measuring 8.5 by 7.75 and valued at $225,000.

This helmet is one of five Met-donated helmets identified as being part of the Bill Blass collection between 1992 and 2002. It joined the Met in 2003. Within the Gianfranco Becchina archive is a page of five Polaroid photographs,which depict multiple bronze helmets, including those from the Bill Blass collection which are part of this seizure.

Also, among the Becchina archive documentary material are two business documents believed to be related to these transactions.

The first is a 1989 multi-page export document for a grouping of objects being exported to Merrin Gallery indicating the sale of three helmets, one of which is described as "one South Italian Greek Bronze Helmet of the so-called Corinthian type, with bronze pins remaining for the attachment of the lining. "

The second is a fax correspondence from Becchina to Samuel Merrin discussing some sort of transfer regarding a single helmet and Acanthus Gallery.

As mentioned previously, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure. Merrin Gallery appears in connection with multiple objects within this seizure.

__________

n. A bronze helmet of South Italian-Corinthian type, dated mid-4th-mid-3rd century BCE, measuring 7.75 inches tall and valued at $125,000.

Like the previous one, this helmet is one of five Met-donated helmets identified as being part of the Bill Blass collection between 1992 and 2002. It joined the Met in 2003. Within the Gianfranco Becchina archive is a page of five Polaroid photographs, which depict multiple bronze helmets, including those from the Bill Blass collection which are part of this seizure.

Also, among the Becchina archive documentary material are two business documents believed to be related to these transactions.

The first is a 1989 multi-page export document for a grouping of objects being exported to Merrin Gallery indicating the sale of three helmets, Two of which are described as "two South Italian Greek Bronze Helmets, both decorated with incised animals, one with restings [sic] of a plume holder on top."

The second is a fax correspondence from Becchina to Samuel Merrin discussing some sort of transfer regarding a single helmet and Acanthus Gallery.

As mentioned previously, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure. Merrin Gallery appears in connection with multiple objects within this seizure.

__________o. A bronze helmet of Apulian-Corinthian type dated 350-250 BCE, measuring 12 inches tall and valued at $175,000Like the previous one, this is one of five Met-donated helmets identified as being part of the Bill Blass collection between 1992 and 2002. It joined the Met in 2003. Within the Gianfranco Becchina archive is a page of five Polaroid photographs, which depict multiple bronze helmets, including those from the Bill Blass collection which are part of this seizure.

Also, among the Becchina archive documentary material are three paper business documents.

The first is a 1989 multi-page export document for a grouping of objects being exported to Merrin Gallery indicating the sale of three helmets, two of which are described as "two South Italian Greek Bronze Helmets, both decorated with incised animals, one with restings [sic] of a plume holder on top."

The second is a fax correspondence from Becchina to Samuel Merrin discussing some sort of transfer regarding a single helmet and Acanthus Gallery.

The third is a photocopy of this object with a red line through the image and v/ Me written below. While not conclusive, V/Me most likely refers to venduto (sold) Merrin.

As mentioned previously, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure. Merrin Gallery appears in connection with multiple objects within this seizure.

__________

p. A white-ground terracotta kylix attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter, dated ca. 470 BCE. measuring 6.5 inches in diameter and valued at $1,500,000.

This rare Terracotta kylix is the second highest value item of all 21 artefacts seized. It joined the Met in 1979. Unfortunately it too was purchased via the Galerie Antike Kunst Palladion.

As mentioned above, Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

q. A marble head of a bearded man, dated 200-300 CE, measuring 12.2 inches tall and valued at $350,000.

This marble head of a bearded man joined the Met in 1993, purchased from Acanthus Gallery operated by Brian Tammas Aitken. Gianfranco Becchina archive documents an October 1988 sales receipt to Aitken for "3 Roman Marble heads" for 85,000 Fr.

As mentioned above, Aitken's name comes up frequently as having bought from red flag dealers and appears on two different objects in this Met seizure. Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

r. A terracotta statuette of a draped goddess, dated 450-300 BCE, measuring 14.75 inches tall and valued at $400,000.

This terracotta statuette of a draped goddess was donated to the Met by Robin Symes in 2000, in memory of his deceased partner Christos Michaelides. His name appears in connection with four different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

s. A bronze statuette of Jupiter, dated 250-300 CE, measuring 11.5 inches tall and valued at $350,000.

This bronze statuette of Jupiter was acquired by the Met via Bruce McAlpine in 1997. Prior to his death, UK dealer McAlpin had dealings with Robin Symes, Giacomo Medici, and Gianfranco Becchina.

__________

t. Marble statuettes of Castor and Pollux (on loan), dated 400-500 CE, measuring 24 inches tall and valued at $800,000.

The Dioskouroi had been on anonymous loan to the Metropolitan Museum since 2008 as L.2008.18.1, .2. While the Museum's loan accession record has been removed, a Met catalogue informs us that the statues were "probably from the Mithraeum in Sidon, excavated in the 19th century".

With a bit more digging Dr. David Gill was able to get further details from the Met itself. They indicated the pair had come from an "ex private collection, Lebanon; Asfar & Sarkis, Lebanon, 1950s; George Ortiz Collection, Geneva, Switzerland; collection of an American private foundation, Memphis, acquired in the early 1980s".

At some point along their journey, the pair passed through the Merrin Gallery where they were published by Cornelius C. Vermeule, in Re:Collections (Merrin Gallery, 1995).

While a seemingly professional photo of these objects exists in the confiscated Robin Symes Archive, that photo depicts the object prior to restoration. In that photo, Castor's leg, and the leg of his horse behind him, are missing. By the time they arrive to the Met on loan, the two limbs have been reattached.

As mentioned above, Merrin Gallery appears in connection with multiple objects within this seizure.

__________

and lastly,

u. A fragment of a terracotta amphora attributed to the Amasis Painter, dated ca. 550 BCE, measuring 3.25 by 4.5 inches and valued at $2,000.

This terracotta amphora fragment is attributed to the Amasis Painter. It is one of many examples of fragments bought via Gianfranco Becchina's gallery, Galerie Antike Kunst. It was acquired+gifted by Dietrich von Bothmer to the Met in 1985.

Gianfranco Becchina's name or company name appears in connection with twelve different objects in this Met seizure.

__________

But these seized pieces are more than the sum of these numbers. They tell us a lot about this one museum's particular lethargy in dealing with or voluntarily relinquishing problematic pieces before being handed a court order.

One thing is certain though, museums reputations certainly do not benefit when dragged into adversarial, long-winded, and sometimes costly claims for restitution. Nor do they benefit from having their name up in lights when objects are seized on the basis of investigations the museum would have been wise to have done themselves.

Waiting until either of the above happens also runs counter to, and impedes, the essential purposes of museums, which should be about presenting their collections in innovative ways, and fostering understanding between communities and cultures. The Met would have been better off providing open and equitable discourse about their collection's problems before their hand was forced, as waiting until after says a lot about their true collecting values.

When museums hedge their bets, hoping that the public's memory is short, or crossing their fingers that source countries are too disorganised, too undermanned or to poor to spend hours looking for problematic works they will pay the price later. Far better to avoid the painfully slow, one seizure after another reality, and the negative spotlight and mistrust that comes with it, by doing what all museums should be doing, i.e., conscientiously conducting the necessary provenance research and due diligence on their past and potential acquisitions.

|

| Image Credit - HSI - ICE |

To close this article, we would like to announce that today, New York DA Bragg returned 58 stolen antiquities valued at over $18 million, to the people of Italy, including a goodly number of the 21 pieces mentioned above.

|

| Image Credit - HSI - ICE |

In closing, ARCA would like to thank DA Bragg, Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos, Chief of the Antiquities Trafficking Unit; Assistant District Attorneys Yuval Simchi-Levi, Taylor Holland, and Bradley Barbour, Supervising Investigative Analyst Apsara Iyer, Investigative Analysts Giuditta Giardini, Alyssa Thiel, Daniel Healey, and Hilary Chassé; who alongside Special Agents John Paul Labbat and Robert Mancene of Homeland Security Investigations as well as Warrant Officer Angelo Ragusa of the Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, Dr. Daniella Rizzo, Dr. Stefano Alessandrini, and Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis gave crucial contributions to the knowledge we have about when, and where, and with whom, these recovered artefacts circulated.

ARCA would also like to personally thank Assistant District Attorney Bogdanos for the trust he puts in the contribution of forensic analysts inside ARCA and working with other organisation. He and his team's approach and openness has proven time and time again, that such collaboration is worthwhile and fruitful.

By: Lynda Albertson

antiquities looting,Antiquities Trafficking Unit - ATU,India,Matthew Bogdanos,Michael Steinhardt,New York District Attorney,restitution

antiquities looting,Antiquities Trafficking Unit - ATU,India,Matthew Bogdanos,Michael Steinhardt,New York District Attorney,restitution

No comments

No comments

%20(1).png)

.png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

%20with%20silver%20handles%20late%204th%E2%80%93early%203rd%20century%20B.C..png)

%20ca.%20530%20B.C.%20Attributed%20to%20the%20Amasis%20Painter.png)

%20ca.%20470%20B.C.%20Attributed%20to%20the%20Villa%20Giulia%20Painter.png)