Art Institute of Chicago,Egon Schiele,Grünbaum,Manhattan District Attorney

Art Institute of Chicago,Egon Schiele,Grünbaum,Manhattan District Attorney

No comments

No comments

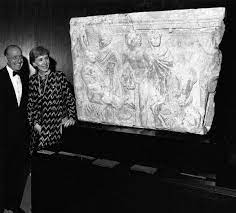

A landmark win in the fight for restitution: Egon Schiele’s Russian War Prisoner ordered returned to Grünbaum heirs

This week's ruling follows on a broader pattern of Holocaust-era restitution in recent years. Over the past two years, the New York District Attorney's Office in Manhattan has been successful at convincing museums and private collectors to voluntarily relinquish Schiele art works once held in Grünbaum’s collection after walking them through the sometimes complex but ultimately compelling evidence. Those earlier institutions recognised the evidence presented, as well as the historical injustice and took action to right long-standing wrongs.

The Art Institute of Chicago took a different stance however. Rather than accept the findings of provenance research and the investigative conclusions regarding the Nazi-era seizure, the museum opted to challenge the jurisdiction of the Manhattan District Attorney to to initiate a criminal proceeding, treating the museum’s Schiele as stolen property, in what the museum argued was a civil dispute with a good faith purchaser. The DA’s office, however, viewed the work as stolen property under New York law—a stance the court ultimately upheld in Judge Drysdale’s critical court ruling.

The decision, reported this week in The New York Times, marks a pivotal moment not only for the Grünbaum family but for the broader field of Holocaust-era restitution. The ruling sends a clear message: museums and collectors cannot hide behind good faith acquisition when the underlying reality is the object is stolen property.

This victory is the culmination of years of tireless advocacy and legal action initiated as far back as 2005. It reaffirms the legal and moral imperative to return artworks looted under persecution, particularly when the theft is linked to genocide. As the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office continues its work investigating and supporting the recovery of looted art, this case may set a powerful precedent for future restitution claims still pending in courts and museum storerooms around the world.

With this win, hope remains alive that other works from Grünbaum’s collection—still held by private collectors and public institutions—may eventually be returned to their rightful heirs. Justice, in this case, may have taken nearly a century, but it is a testament to the enduring power of memory, persistence, and the rule of law.

By: Alice Bientinesi