Thursday, February 25, 2021 -  art theft,Caravaggio,Charley Hill,Edvard Munch,Francesco Lazzaro Guardi,Russborough House,The Scream

art theft,Caravaggio,Charley Hill,Edvard Munch,Francesco Lazzaro Guardi,Russborough House,The Scream

1 comment

1 comment

art theft,Caravaggio,Charley Hill,Edvard Munch,Francesco Lazzaro Guardi,Russborough House,The Scream

art theft,Caravaggio,Charley Hill,Edvard Munch,Francesco Lazzaro Guardi,Russborough House,The Scream

1 comment

1 comment

The art of loss: Mourning "Charley Hill" the intrepid undercover agent who recovered Edvard Munch's "The Scream"

In the first days after Charles Hill's death, on Saturday, February 20th, words completely eluded me. Trying to think of what I could write or should write, and knowing a man's successes are not a sum of his career, I also thought to his family trying to cope with his unexpected loss. These are the people who knew Charley, not as a respected Detective Chief Inspector or private investigator, but by the more important titles he held: Father and Husband.

In writing this goodbye, I mulled over some of the conversations Charley and I had over the years, most of which occurred in letters that often made me laugh out loud for their wit and sarcasm, doled out in equal measure. More rarely, when our paths would cross in Rome or in England, I was fortunate enough to listen to his soft-spoken quips about art as currency in the underworld, about clan funerals in Tullamore, County Offaly, or his work with the Historic Houses Association.

I remember one conversation seven years ago almost to the day when Charley was doing what Charley loved, chasing a pair of picturesque Venetian scenes by the 18th-century Italian painter Francesco Lazzaro Guardi. These two landscape paintings depicting Venice, really bothered him, as they are the last of eighteen artworks stolen by Dublin gangster Martin Cahill's gang during a 1986 burglary at Russborough House, that remain missing.

Back in 1993 Hill had already worked on the multicountry investigation that recovered Goya’s Doña Antonia Zárate, Gabriel Metsu’s Man Writing a Letter, Antione Vestier’s Portrait of the Princesse de Lamballe and Johannes Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid, taken from the same stately Irish home. Although the Vermeer pleased Charley the most, perhaps because it was one of just two Vermeers in private collections, (the second is owned by Queen Elizabeth II), it was the two Guardi paintings that remained outstanding that prevented him from closing the Russborough House case with satisfaction. For the paintings already recovered, Hill had posed as a dapper, if not dubious, art dealer claiming to have Arab buyers lined up to purchase the stolen paintings. To bring them home, he met with the underworld accomplices alone in a multi-storey car park at the Antwerp airport.

But back to our conversation in 2014. For more than a year Charley had been following up on every vexing lead, no matter how improbably proposed, trying to get the two stolen Guardi paintings back. He wanted to keep a promise he had made to Lady Beit eighteen years earlier when they had met and discussed his work on the recovery of Russborough's artworks. In our conversation he described his hunt for the paintings and his relationship with one of his more frustrating Irish informants unabashedly, saying "we're a bit like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, and I'm the short, fat fox trotter on the donkey, but with all of the best lines."

Hill understood that many of the leads he was given, and the promises being made, were akin to tilting at fabled windmills. Despite this, he felt driven to see each through, tackling each misadventure and subsequent disappointment with sardonic humour, saying it only takes one solid piece of evidence. In many ways it was this perseverance, coupled with earthy wit and optimism that all puzzles could eventually be solved, that kept him tenaciously plodding forward, where others might have given up.

Retiring from the Metropolitan Police in London in 1997 Hill could have sat back and enjoyed the fact that his name will forever be remembered for the recovery of Pieter Brueghel's Elder's Christus en de overspelige vrouw stolen from the Courtauld Gallery in 1982 and the recovery of Edvard Munch's Der Schrei der Natur, more commonly known as The Scream, stolen from the Nasjonal Museet in Oslo during the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer.

He could have relaxed in a pub, over a blended scotch telling the story of how he was laid out on the ground and handcuffed alongside the criminals when he was unable to get a signal to his German counterparts, during the recovery of a hoard of paintings and statues stolen in Moravia and Bohemia that included Lucas Cranach's The Old Fool from the National Gallery in Prague. But instead, after the Marquess of Bath received a ransom demand, Charley continued post-retirement chasing up leads on the missing Riposo durante la fuga in Egitto by Tiziano Vecellio, better known as Titian. That work had been stolen in January 1995 from the grand rooms of the Elizabethan manor Longleat.

After seven years and a succession of false leads, one lead on the 16th century Renaissance painting Rest on the Flight into Egypt paid off. To bring the painting home required coordinating a lot of moving parts, the last of which involved Charley going to a simple bus stop in Richmond, south-west London where he was to find the Titian undamaged, stashed without its frame and wrapped in brown parcel paper, plinked inside a nondescript, red, white, and blue plastic shopping bag.

But aside from these victories, are the many works that remained outside Hill's reach. Art objects in which he never lost hope of being recovered. The most famous of these being the 13 works of art stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston on March 18, 1990.

A Fulbright Scholar in his early years before joining Scotland Yard, Hill had studied history at Trinity College, Dublin, most likely where is knowledge of Ireland and the Irish began. He then went on to attend King’s College in London, where he read Theology and at one point considered becoming a member of the Anglican clergy.

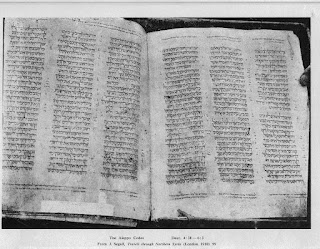

Perhaps this is why Charley was good at talking with the local clergy and members of their flock, both righteous and sinner. For Hill, the lost and stolen icons and religiously significant objects of worship deserved to come home as much as the better-known paintings. Doggedly, he never gave up on searching for a cross stolen from the Church of San Giuseppe in Piazza Armerina in Sicily, the missing pages from the Aleppo Codex, the oldest Hebrew Bible, or Italy's most famous painting, Caravaggio’s Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence.

|

| The Oratory of San Lorenzo, in Palermo, missing its “Nativity” by Caravaggio |

In talking about art and why it's worth saving, in one of his particularly poignant moments, Charley told a colleague, Tracy Citron "Art is part, in substance and theory, of the values we have as human beings. There are 7 or 8 billion of us, and we need art, especially great art and architecture, literature and ideas and traditions to help us be and become more fully human. I think that is our common, even though warring or conflicting, humanity. In my opinion, art is God given. Admittedly, a lot of art is bullshit and many artists and art world types are assholes, but still, art is a God given grace."

As I reminisce on this, I try and remind myself that with every passing, a person leaves behind something to be remembered by and to draw comfort from. Sometimes it is a pair of tortoiseshell spectacles, a Donegal tweed jacket made of Irish lowland wool, or saved letters read and reread. I will think of Charley every time I see the fruit of his labours hanging back where they rightfully belong. Where these works of art can be enjoyed by this generation and many generations after.

Charley leaves behind his wife Caroline, his three children Elizabeth, Christ and Susannah, and histwo grandchildren, Georgia and Olivia.

NB: His friends called him Charley, never Charles and certainly not Charlie.

By: Lynda Albertson

|

| The two missing Russborough House paintings of 18th Century Venice by Francesco Lazzaro Guardi, that Charley Hill was chasing. |