antiquities traffficking,Arthur Brand,Costa Rica,FBI,Germany,Guatamala,huaqueros,Leonardo Patterson,Mayan,mesoamerican,Mexico,Michel van Rijn,Peru,pre-columbian,Spain

antiquities traffficking,Arthur Brand,Costa Rica,FBI,Germany,Guatamala,huaqueros,Leonardo Patterson,Mayan,mesoamerican,Mexico,Michel van Rijn,Peru,pre-columbian,Spain

No comments

No comments

The Life and Death of Antiquities Trafficker Leonardo Patterson: A Dealer in Stolen History

|

| 1992 photo of Leonardo Patterson with Pope John Paul II |

This morning Arthur Brand posted that Leonardo Augustus Patterson, euphemistically known as a dealer and collector of ancient art, but long accused of trafficking looted pre-Columbian artefacts, has died. His passing, on 11 February in Bautzen, Germany, at the age of 82, marks the end of a decades-long saga of intrigue, deception, and international investigations conducted by the F.B.I., and the National police in Mexico, Spain, Peru, Guatamala and Germany, all of which centred around his circulation and sale of illicit ancient artefacts as well as forgeries.

Born in Costa Rica to Jamaican parents in 1942, Patterson rose to prominence in the booming, Janus-faced antiquities market of the 1960s and 1970s. Over the years, he developed a reputation as both a knowledgable connoisseur as well as a trafficker, and occasional dealer in forgeries, who amassed an inventory of ancient artefacts worth millions and maintained homes in New York, Mexico city, and Munch. Many of the pieces he handled are believed to have been plundered from sites in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, Guatemala, and Peru, all countries rich in archaeological histories.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Mesoamerican archaeological sites were subjected to rampant looting, driven in part by an increasingly insatiable global demand for Pre-Columbian material. In Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize, ancient Maya, Olmec, and Aztec sites were raided by looters, often referred to as huaqueros who left behind a path of damage or devastation in their wake.

These individuals, working in well-funded and well-connected trafficking networks, unearthed jade masks, ceramic figurines, jewellery, carved stelae, and codices, stripping important archaeological sites of invaluable movable cultural heritage. With the rise of private collectors and museum acquisitions in Europe and the United States during this period, many of these black market artefacts ended up in prestigious collections as well as in institutions, purchased through dealers such as Patterson, or those who bought directly from him.

Governments in Mesoamerica responded to their losses with stricter cultural patrimony laws. Yet ,despite increased legislation, enforcement remained inconsistent. This in turn allowed the looting to persist, and further resulted in damaging the historical record of what we know and can document about the sites and customs of these ancient civilisations.

Patterson’s dealings in cultural property, on and over the edge of legality, placed him at the centre of legal controversies.

In his first overt brush with the law, on 21 May 1984, the FBI charged Patterson federally with wire fraud for trying to sell a fake Mayan fresco to an art dealer in Boston. In that instance he pleaded no contest, contending that he was set up by FBI officers, who he claimed held had a vendetta against him. Despite the felony conviction, he was sentenced lightly, to probation.

A year later, and while still on probation for his earlier conviction, Patterson was arrested upon arrival at the Dallas-Fort Worth airport for illegally importing a 650 and 850 CE, pre-Columbian ceramic figure and 36 sea turtle eggs, a violation of the Endangered Species Convention. In that case, the flamboyant merchant claimed that the pre-Columbian artwork was a newly made souvenir, but openly admitted he planned to consume the eggs as part of his health regimen, even describing how he would eat them. In his own defense, he stating that he thought he only had to declare the endangered turtle eggs when he arrived at his final destination.

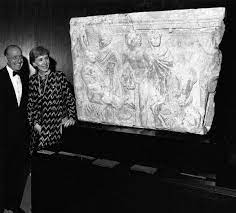

|

| Leonardo Patterson in his apartment in Munich. |

By the 1990s, Patterson had moved away from his repeated US headaches to Europe, relocating to Munich, where he began holding large exhibitions and making sales in France, Germany, and Spain. There, he befriended and sold ancient art works to a large circle of wealthy collectors and by 1995, was named Costa Rica's cultural attache to the U.N. Interviewed by the newspaper, Der Spiegel, journalists recorded that at the highest point in his selling career, the extravagant dealer had been chauffeured around the city in a blue Rolls Royce and sponsored his own polo team, which included four players and 12 horses.

In 1995, this also became complicated in Europe, when Patterson's activities were linked publicly in the New York Times to Val Edwards, a successful, if not controversial smuggler. Edwards told journalists that over the course of a decade he had covertly brought 1000 museum-quality artefacts into the United States which had been plundered from various sites in Guatemala and Mexico.

With pre-Columbian artworks fetching record prices and while the United States Customs Service officials concentrated on the drug trade, Edwards claimed that he got away with smuggling by posing as a businessman, entering the United States with restaurant equipment and a ready-made alibi that the objects he possessed were cheap tourist reproductions, to be used to decorate a Mexican restaurant he planned to open. In his ten years of smuggling, Edwards was never arrested, and his bags were only searched once, for drugs.

Not long after he this link to Edwards was made public, Patterson's honorary role with the UN was revoked.

One of the most important pieces tied to Patterson's illicit activities is this three-foot-wide Mochica headdress of a tentacled zoomorphic sea god. In was looted from a Moche funerary site in the Jequetepeque valley in northern Peru during a wave of clandestine excavations following the discovery of the famous lord of Sipán tomb. The artefact had been stolen by a man named Ernil Bernal, who led a band of huaqueros who tunnelled into one of the pyramids located at Huaca Rajada. Bernal in turn sold the piece to a Peruvian collector named Raul Apesteguia, who later sold the extremely rare artefact to Patterson.

On 26 January 1996 Apesteguía was robbed, and found beaten to death in his home. Authorities in Peru believe that the collector died at the hands of an antiquities trafficking mob with whom he had been associated. Though never charged, Patterson's name surfaced as a person of interest in connection to this murder investigation, as objects associated with Apesteguía, including this magnificent gold piece, were identified in circulation with Patterson.

While it is not possible to list all of Patterson's antics in one blog post, here are a few.

In 1997 Patterson staged an exhibition at the Museo do Pobo Galego in Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain, sponsored by the Galicia regional government. During this event, several experts voiced concerns that some of the artefacts might be forgeries, including an Olmec throne described as made of fired clay, something the Olmecs weren't known for. Patterson filed a $63 million defamation lawsuit against the dissenting experts, only to later withdrew his charges.

Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva, who reviewed a copy of Patterson's museum exhibition catalog, identified more than 250 ancient Peruvian pieces, mostly from tombs raided in the late 1980s, one of which was the gold Peruvian Mochica headdress mentioned earlier.

In 2004, after receiving a tip, customs officials in Germany targeted an air freight delivery at Frankfort Airport containing archeological artefacts from Mexico and simply waited until Patterson's daughter showed up. That same year, and based on the contents of Patterson's 1997 exhibit catalogue for the Santiago de Compostela exhibition, and identifications from archaeological experts, Peru issued an arrest warrant for the dealer.

In 2006, and acting on information from Michel van Rijn and Arthur Brand, London's Metropolitan Police successfully recovered the Mochica headdress of a tentacled zoomorphic sea god when Van Rijn posed as a buyer during a visit to the London office of Leonardo Patterson's lawyer. That piece was returned to Peru later that summer.

Later that same year, on 30 October 2006, Peruvian commander George Gamarra Romero received a confidential email inbox in which Spanish colleagues had notified him that Spanish authorities had a tip that more than a thousand of pieces tied to Patterson were being stored in a moving warehouse in Galicia. Executing a search warrant in early 2007, police documented rare Mayan and Aztec pieces, Incan gold, and a variety of other pre-Columbian relics were suspected to have been illegally obtained. As part of this police investigation, and based on a request from Peru, Spain seized 45 Peruvian cultural objects, many of which were determined to have been looted from Sipán and La Mina.

But before Spanish police could investigate the remaining pieces further, Patterson had the rest of the items moved to Munich in March 2007. Sparking further questions, Patterson disputed the sequester in Spain and claimed that all of the artefacts were part of a loan from German millionaire Anton Roeckl.

As the international cases progressed, German authorities seized more than 1,000 Aztec, Maya, Olmec and Inca antiquities from Patterson in April 2008. The pieces were packed into more than a hundred crates held in a Munich warehouse.

In September 2011 Patterson was arrested at the Mexico City international airport while traveling to his native Costa Rica based on an Interpol red notice issued by Guatemala and a location order issued in Mexico by the Specialized Unit for Investigation of Crimes against the Environment and Provided for in Special Laws of the PGR, for the alleged crime of theft of archaeological goods and pieces. In December 2012, a criminal court in Santiago de Compostela put the dealer on trial for violating export regulations relating to cultural artefacts when he moved his collection to Munich. Unfortunately, Patterson wasn't present at the trial, as a German doctor had issued him a certificate of poor health saying that he was unable to travel.

|

| Leonard Patterson during the trial in Spain. |

On 28th March 2013, at yet another airport, Patterson is again arrested, this time at the Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport in Madrid on the bases of Interpol notices from Guatemala and Peru. While awaiting a decision on extradition to Latin America, he was housed at the Madrid V Penitentiary Center, Soto del Real.

Wanted since 2008, Guatemala's Office of the Public Prosecutor for Crimes against Cultural Heritage requested Patterson's extradition for the crimes of illicit export of cultural property and the illegal possession of 269 looted objects purportedly part of the larger "Patterson Collection" a batch of 1,800 archaeological objects from countries such as Mexico, Guatemala and Peru, which he's exhibited in Santiago de Compostela. But as the requests progressed, Patterson was released from custody for health reasons 10 months after his arrest in January 2014. Although he had been ordered to remain in Spain, he immediately left for Munich.

Back in Germany, he racked up another charge, for selling a 10 percent share of an allegedly fake Olmec head (the Olmec were an ancient civilization in Mexico) to a businessman from nearby Starnberg for €85,000. In that case the Court in Munich found him guilty of "deceptively selling a piece of recent manufacture as an archaeological artefact of Mexican origin to a German citizen" and "possessing looted artefacts."

Given his advancing age, as is too often the case with elderly lifetime traffickers, Patterson was sentenced in Germany to probation, plus home confinement for three years, ordered to return two wooden Olmec head carvings to Mexico and fined approximately $40,000. Arthur Brand, a witness in that trial, testified that Patterson had told him that the returned pieces had been taken by a tomb raider from an archaeological dig in El Manatí, Mexico, a sacred site of the Olmec people.

In his 2016 interview with Der Speigel, Patterson openly elaborated on his business model, and admitted to working with Mexican intermediaries who travelled to Munich on a regular basis. "They worked together with the illegal excavators," he stated. "Their focus was on fresh goods, primarily because of the prices. They had to know where digging was currently going on. They always got it at the place where it was found. They knew the people in the villages."

Patterson’s death leaves many questions unanswered about the final fate of the thousands of artefacts he once controlled. While some have been returned to their countries of origin, many others remain in legal limbo, or in the hands of private collectors, some of whom are unaware of—or indifferent to—their questionable provenance.

|

| A Paris warehouse of Patterson's merchandise. |

Noting his death today, some say, why not let the dead rest? I myself disagree, as this man certainly didn't.

By Lynda Albertson