|

| Rear entrance to musée d'art modern de la ville de Paris |

By Catherine Sezgin ARCA MA '09

Correction: The original version assumed that the window's metal accordion shutters were exterior; a visit to the museum in July 2010 showed that the metal shutters were on the inside of the windows.

For six weeks, the Musée d’Art Modern de la Ville de Paris has waited for parts to fix their security system. Last night, five paintings valued at 100 million euros were stolen between Wednesday evening and Thursday morning from the building in one of the most fashionable districts in Paris, just blocks from the Pont de l’Alma where Princess Diana died in 1997 and north of the Eiffel Tour.

Time Magazine reported in "

The French Art Heist: Who Would Steal Unsaleable Picassos?":

According to officials, the thief cut through a gate padlock and broke a window to gain access to the museum, all without alerting the security guards or triggering the museum's alarm system. A security camera filmed the intruder making off with five paintings, but the works were only discovered missing during morning rounds just before 7 a.m. on May 20.

The thief accessed the collection though a rear window of the east wing of the Palais de Tokyo.

No further details have been submitted by museum or law enforcement officials. One likely scenario is that the thief may have driven a scooter along the Avenue du New York that runs parallel to the Seine where the street has signs posted forbidding parking and heavy black gates that separate the road from the wide sidewalk as is common in central Paris.

Underneath the balcony terrace of the rear portion of the ground floor of the museum, a recessed doorway marked #14 may have provided excellent cover for a parked scooter. The doorway is located about eight to ten feet from the road. Although a barrier exists between the street and the sidewalk, the openings are wide enough for a scooter to exit onto the sidewalk and then re-enter the traffic later.

After hopping up to the balcony, the thief may have taken out – probably from a bag slung over his shoulder – a tool that would have broken the window and then sawed-off the padlock (Time Magazine) that secured the window’s metal accordion shutters inside the full-story windows. Opening these metal shutters would have created a loud and persistent screeching sound as the metal rubbed against the sliders in the window casements.

Once the glass window was exposed, the intruder may have used the handle of the cutter to smash open the middle panel of the window and to climb into the building. The thief may have known that the security alarm would not alert the security guards, the police, or even notify anyone that the building had been broken into. He would also have known that no security guard would have been patrolling nearby the area of the stolen paintings.

A security video camera caught a masked man entering through the window. The thief may have decided it was too difficult to turn off the security camera and just wore a covering to obscure his identity.

Inside, the intruder selected five paintings from the same period that were most likely located in either the same room or close to one another, removed the works from their frames, and left without disturbing the three night security guards.

The thief broke open a gate, smashed the glass in a window, and had time to remove five paintings from their frames? Why did not one of the guards hear or see any of this activity, especially since the security patrol was aware that the alarm was disabled?

The thief may have removed the paintings from their frames so that they would be easier to carry while he drove away on his scooter. All the paintings, without frames, were of small to mid-size and could easily be carried.

A thief with an automobile and a second driver – who would be waiting in the car since there was no place to park legally – would have saved time by taking the paintings with their frames down from the walls and just thrown the paintings into the back seat of the car.

The empty frames were finally discovered Thursday morning by 6 or 6.30 a.m. by the one of the three security museum guards.

The Brigade de Répression du Banditsme, the elite police unit that fights organized crime and art theft, was in charge of the investigation.

The day of the theft, the police had littered the terrace with yellow evidence markers around the frames leaning against the balcony. The police officers were measuring the frames and various locations on the patio.

Chritophe Girard, deputy culture secretary in Paris, estimated the value of the stolen paintings at 100 Euros ($123 million). The five missing paintings are reported as:

“Le pigeon aux petits-pois” (The Pidgeon with the Peas), an ochre and brown Cubist oil painting by Pablo Picasso worth an estimated 23 million euros;

“La Pastorale”, an oil painting of nudes on a hillside by Henri Matisse about 15 million euros. Matisse, the leader, of Fauvism, was a rival and friend of Pablo Picasso. Matisse painted this oil on a 46 x 55 centimeter canvas in 1905.

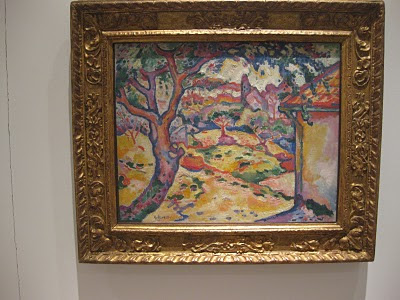

“L’olivier prés de l’Estaque” by Georges Braque;

“La femme a l’eventail” (Woman with a Fan) by Amedeo Modigliani;

and “Nature-more aux chandeliers” (Still Life with Chandeliers) by Fernand Leger.

According to Paris’ mayor Betrand Delanoe, the museum’s security system, including some of the surveillance cameras, has not worked since March 30 and has not been fixed since the security company is waiting for parts from a supplier (Bloomberg.com, “Picasso, Matisse Paintings Stolen From Paris Museum”, May 20, 2010).

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris is located at 11, avenue du Président Wilson in the 16th arrondisement in Paris, just three blocks west of the Alma Metro station and one block east of the Place d’Iéna and another metro station. The museum, closed on Mondays, is free to visitors for the permanent collection. All five paintings belonged to the permanent collection gathered from private collectors’ generous gifts to Paris’ city museum of modern art.

The 1911 Picasso still life was a gift from Dr. Girardin in 1953. It was featured in the International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life in 1937.

The building for the museum was constructed in 1937 and officially opened in 1961 with a collection built from donations from private collectors, especially that from Dr. Girardin. The stolen works were from the oldest part of the collection.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris,unsolved art theft

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris,unsolved art theft

No comments

No comments

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris,unsolved art theft

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris,unsolved art theft

No comments

No comments