ARCA,art law,conference,Edgar Tijhuis,Saskia Hufnagel,UNESCO,UNIDROIT

ARCA,art law,conference,Edgar Tijhuis,Saskia Hufnagel,UNESCO,UNIDROIT

No comments

No comments

Interview with Professor Saskia Hufnagel: Cultural Heritage Law, Art Crime, and the ARCA Experience

This series aims to offer future participants a personal glimpse into the people who teach with ARCA, the community around it, and what to expect in the coming year.

|

| Saskia Hufnagel |

I started off as a German Criminal Lawyer in a little town close to the Dutch border and had nothing to do with art at all. In my practice I got very interested in cross-border crime and law enforcement dealing with it and was very lucky to receive a scholarship funded jointly by the European Commission and the Australian National University to pursue a PhD in the area of international law enforcement cooperation.

You have been part of ARCA’s community for some time. Have attended the annual Amelia Art Crime Conference?

In the past 14 years, I have only missed two ARCA conferences and the time in Amelia each year is extremely important for my research as it is inspiring and envigorating, creating new contacts with wonderful people in the field and bringing me up to date with the newest research. There are so many memorable moments from these conferences, but the first conference I attended was really the one that changed my career, inspired me to keep working in the field and initiated friendships that have lasted now for many years (though new ones can be added to the list each year!).

From your perspective, what makes ARCA’s Postgraduate Certificate Program truly unique and valuable?

There is no other program like ARCA. University programs will situate a course mainly within one discipline, so you rarely get the same variety of interdisciplinary knowledge taught within this program elsewhere. Also, ARCA has contacts to some of the most knowledgeable academics and practitioners in the field and brings them together from all around the world to teach the programme.

How does the location in Italy — surrounded by centuries of cultural heritage — enhance the learning experience for participants?

The vibe of the location is very conducive to learning about art and antiquity crime. You see the tomb raiders hang out around the Etruscan tombs that you will be visiting and the taught becomes real. The threat to culture and the importance of preserving it are felt as particularly pressing in this environment. The beauty of the nature and the quality of food and wine obviously also help to bring the student community together and make it an unforgettable experience.

Are there particular site visits or practical elements during your course that you find especially valuable?

My course is pretty dull as law is often not that exciting and I am teaching the law around cultural heritage and the basics of criminal law, property law and international law. I try to make up for the technicalities by using a fair amount of pictures in my slides and doing very interactive classes where students learn by asking questions and engaging with me rather than by having to listen to me droning on about the law. There will still be a bit of that, but I try to keep it as ‘fun’ as possible.

As we look toward the 2026 program, which developments or emerging issues in the field of art crime do you consider particularly important, and how will these be reflected in your course?

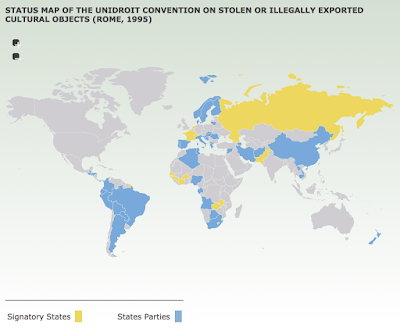

2025 was obviously dominated by the Louvre heist and there is a lot one can learn from this case in terms of criminal law, but also international law and policing. This is obviously just one case and many other events have marjorly impacted cultural property protection in recent years, such as the wars in Ukraine and other parts of the world, making us think about import and export bans and how to enforce them. We will use current examples to explain the law and think about the complexity of the law. How many criminal offence were, for example, committed during the Louvre heist?

What key skills, perspectives, or tools do you hope participants will gain from your course? In what ways can they apply these insights in their professional or academic paths?

The law around cultural heritage/property is important for all areas of art crime research. I hope that students get an understanding of the basics of the law surrounding it to be able to understand, for example, why some moral obligations might not be legal obligations and to see the legal restraints around restitution as well as civil and criminal trials more generally. An understanding of the law is important whether you are a police officer or a gallerist. It sets the parameters within which eiter can move and do business and should be of interest to everyone.

If someone is considering applying to ARCA’s 2026 program, what advice would you give them? And why do you think now is a meaningful moment to engage with this field?

Amelia is a once in a lifetime opportunity to study with a very diverse group of students, people you would otherwise never – or not very likely – meet in your life. Make friends, support each other studying, have fun, enjoy the wide variety of teachers and subjects and take home a great deal of knowledge and a new little family. Art and antiquities crime is a very important field of research but still not many people know about it. Your mission is to change this and get the knowledge you gain at ARCA out into the world. Make people care.

About Saskia Hufnagel

Dr Saskia Hufnagel is a Professor at the University of Sydney Law School. Her research focuses on art crime, transnational and comparative criminal justice and global law enforcement cooperation. Her particular interests are the detection, investigation and prosecution of art crimes in the UK, Germany and Australia from a comparative legal perspective and international and regional legal patterns of cross-border policing. Saskia is a qualified German legal professional and accredited specialist in criminal law. She holds an LL.B. from the University of Trier and an LL.M. as well as a PhD from the Australian National University.

📌 ARCA Postgraduate Certificate Programmes (Italy | Summer 2026)

• Post Lauream I (22 May – 23 June 2026): PG Cert in Art & Antiquities Crime

• Post Lauream II (26 June – 26 July 2026): PG Cert in Provenance, Acquisition & Interpretation of Cultural Property

➡️ Take one track—or combine both in a single summer.