The artist who copyrighted his mind in 2003, Jonathan Keats, questions

the concept of originality in his new book, FORGED: Why Fakes Are the

Great Art of Our Age (December 2012, Oxford University Press).

What is Culture? Tom Keating (1917-1984)

In 1982, British

national television showed Tom Keating demonstrating how he painted in the

style of masters such as Titian and Rembrandt. In his 1977 autobiography The Fake’s Progress, Keating, a former

housepainter who had worked for art restorers, declared the use of inferior

materials (“recklessness”) such as acrylics in ‘oil paintings’ indicated that

his pictures in the style of great masters were never meant to fool the serious

art market.

Rather

than scraping down the old potboilers he bought in junk shops, he simply

cleaned them with alcohol and reprimed them with a layer of rabbit-skin glue.

He painted directly onto this surface, often in acrylics, sometimes brushing on

a layer of darkening varnish before the paint cured. The results were

predictably catastrophic. Even if his synthetic pigments were never detected by

scientific testing, the paint would start to peel in a few decades, betraying

his ruse.

Keating allegedly forged the work of Cornelius Krieghoff, a Dutch

artist of the 19th century famous for his Canadian landscapes. Keats

writes:

A

Dutch artist working in Quebec City in the 1850s, Krieghoff produced thousands

of diminutive farm and tavern scenes, many of which were bought as souvenirs by

British soldiers. Historians came to value them for their detailed documentation

of Canadian customs. Collectors coveted them for their decorative charm.

Dealers delighted in their escalating prices, reaching into the thousands of

pounds by the 1950s. Keating appreciated them for Krieghoff’s skillful

depiction of “jolly little Brueghelesque figures” and for the fact that

Krieghoff “did so many versions of the same picture” – to which hundreds more

could and would be added over the following decade.

In the early 1950s,

Keating sold forgeries through junk shops in south London, then through country

auctions in Scotland where he worked ‘restoring the trifling art collections of

minor Highlands castles’, then on to counterfeiting paintings by artists such

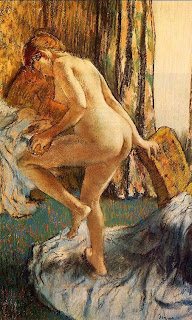

as Degas, Goya and Samuel Palmer whom he claimed possessed him and used him to

create more artworks long after their deaths. A Times of London correspondent,

Geraldine Norman, began unraveling the forgeries of Keating in 1970 but didn’t

publish until 1976. Once confronted, Keating immediately confessed:

Alluding

to the full scope of his forgery, he declared that money was not his

incentive. “I flooded the market

with the ‘work’ of Palmer and many others, not for gain (I hope I am no

materialist) but simply as a protest against the merchants who make capital out

of those I am proud to call my brother artists, both living and dead.”

International headlines

followed Keating, along with a book-deal to be ‘ghost-written’ by Norman’s

husband, Frank, a petty-thief-turned-playwright. However, at Keating’s

three-week trial ended when he fell ill and the prosecutor dropped the case.

Keating recovered and became a celebrity after forging works for more than two

decades in 12 television episodes before he died of heart failure.

art forgery,documentary,kickstarter,Mark Landis

art forgery,documentary,kickstarter,Mark Landis

No comments

No comments

art forgery,documentary,kickstarter,Mark Landis

art forgery,documentary,kickstarter,Mark Landis

No comments

No comments