Australia,book review,Penelope Jackson,Unseen: Art and Crime in Australia

Australia,book review,Penelope Jackson,Unseen: Art and Crime in Australia

No comments

No comments

Book Review: Unseen: Art and Crime in Australia

Author: Penelope Jackson

Publisher: Monash University Publishing, Clayton, Victoria, 2025

Reviewer: Dr Vicki Oliveri, Australian-based Art Crime Researcher

Penelope Jackson's use of the word ‘unseen’ as the main title of her new book is a clever descriptor to employ, as it captures various aspects of art history and art crime in Australia where knowledge gaps exist. Each chapter explores these gaps and provides pertinent details that too often are left out, not only in the backstory of an artwork and art crime, but also in their present status. Jackson further enriches these details by analysing why such gaps exist.

In Chapter One, “An Exhibition of Missing Art”, Jackson presents us with a collection of missing (and still to be recovered) artworks. Included in this “exhibition” is what she dubs the “inaugural ‘known’ theft” [in 1926] from the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) – The Gentle Shepherd, by Scottish artist Sir David Wilkie (p. 12). In this chapter, Jackson makes the important observation that in Australia, “while some missing artworks are acknowledged, others are not. There’s no right answer, or definitive rule, about how to deal with acknowledging missing artworks” (p. 11). As is her style throughout this book, Jackson explores the backstories of this and the other missing artworks, as well as analysing the many aspects of the term ‘missing’ itself.

In Chapter Two, “Artnapping and Recovering Art”, when recounting well-known art thefts, Jackson goes beyond the usual re-telling and delves a bit deeper. For example, with the 1986 theft of Picasso’s Weeping Woman from the NGV she tries to understand what the fascination is with this particular heist (p. 36). The Weeping Woman was recovered but, as Jackson rightly points out, “so often a work’s theft and recovery are not acknowledged by the gallery” (71). As this chapter highlights, it’s not only the missing works that are “unseen” but also details about them.

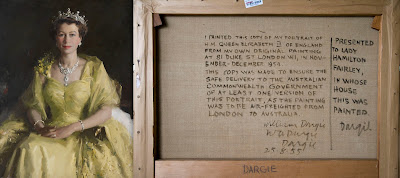

Copies of artworks can also fall into the category of ‘unseen” too, as discussed in Chapter Three’s “A Mania for Copies”. In a world of art forgeries, it is refreshing to read about the place of legitimate copies of art and their role in Australian art and cultural history. Here we read about famed copies such as the ubiquitous Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II (1954) by William Dargie, also known as The Wattle Portrait, in reference to the yellow ballgown worn by the Queen. Then there is the Australian public’s obsession with William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World. The replica that went on tour in Australia was painted in the period 1900 – 1904 and it is estimated that four million people came out to see it (p.85). Many saw the painting “several times” and, as Jackson notes, with a national population of five million at the time, the visitor numbers were indicative of “an incredible event and achievement, demonstrating the popular taste for the subject matter and style of art” (p. 85). Copies have since fallen out of favour with few remaining on display and, over time, copies “can be passed off as authentic artworks” (pp 103-104). This is why provenance research is vital, to help distinguish authentic works from any replicas or intentional fraudulent art.

Chapter Four’s “In Verso” tackles cases of fraudulent art through the lens of the artwork’s verso. It is, in a sense, the backstory of the back-of-a-painting’s story. The details noted on the back of an artwork, and those that aren’t, can provide evidence to “help establish and confirm a work’s provenance” (p. 106). Focusing on the verso is a creative and intriguing method of exploring these cases of art crime.

When it comes to art crime Jackson notes that “Every country has a Dobell” (p.138). She is, of course, referring to the famed Australian artist William Dobell, known (amongst other things) for his Archibald Prize winning portraits of Margaret Olley and Joshua Smith. In her research, Jackson has noted that Dobell’s works have “regularly been at the forefront of illegal behaviour” (p.138), so much so that she devotes the whole of Chapter Five to him – “Stealing Dobell”. In this chapter, Jackson chronicles twenty cases (!) involving Dobell, many not well-known, if at all.

With so many art crimes remaining unsolved, it’s not surprising that the available data on the extent of this criminal activity is hard to come by. Jackson addresses the challenges of data collection, such as the way art crime is classified by Australian criminal law, but she takes the topics of ‘numbers’ a lot further in Chapter Six – “Painting by Numbers”. Money talks so yes, the chapter does begin with monetary value of artworks which so often dominates the headlines (such as the National Gallery of Australia purchasing Jackson Pollack’s Blue Poles in 1973 for a record $1.3M) but, as Jackson notes, “Art historians have traditionally shied away from including monetary information in their narratives” (p. 179). This chapter covers a variety of areas, from the ‘numbers’ provided by art sales, to what is meant by the term “prolific” (a word artists are often tagged with), to acknowledging the role data and statistics can make in “redressing the imbalances of individual artists, and group of artists, as the subject of exhibitions or being represented in collections” (p.199) – trying to make the unseen, seen.

Finally, in Chapter Seven, “Damaged Goods”, Jackson profiles a number of artworks that have been damaged by accident, vandalism, theft, fires, and natural disasters, and how an “object’s status can change irrevocably when damaged, regardless of how good its restoration is” (p. 218). Cases include the devastating destruction caused by the unprecedented level of flooding in Lismore in 2022. Despite staff following their Disaster Plan, Lismore Regional Art Gallery suffered terrible losses, where the “final tally saw 60% of the collection deemed unsalvageable” (p.226). This has understandably led to questions being asked about the efficacy of Disaster Plans and the locations of cultural institutions (p. 227). The chapter also looks at the rise of activism which garners attention through vandalising art.

By adopting a holistic narrative approach, that goes beyond the typical finish line of other historical accounts of art crime, this book becomes an exemplar on how to write a full history of an art crime, and the life of an artwork itself. And for those new to art crime Jackson provides definitions throughout the book of the different types of crimes committed against art, including unpacking the tricky terms 'fraud'; and 'forgery'; and their application in Australian criminal law. There is also a handy glossary.

Overall, this book is such a good read because, along with the themes and backstories developed in this book, Jackson rewards the reader with lots of art-historical gems scattered throughout the text. For example, the serendipitous way in which she came across an unfamiliar colonial artist, Eliza Blyth, who created beautiful botanical artworks but who has all but been forgotten (pp.25-26). Then there is poignant case of a stolen Albert Namatjira painting, Areyonga Paddock, James Range (1957) which he had gifted to the girls at the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls. A plaque had been attached to the painting’s frame noting that it had been presented to the girls there. Sadly, although the painting was recovered, the plaque was missing, which caused the former residents significant hurt (pp 70-71). Then you have the curious case of the nineteenth century painting Chloé, by Jules Joseph Lefebvre, which suffered numerous attacks and eventually became a “landmark of Melbourne’s urban history” (pp. 223).

In the book’s “Afterword” Jackson writes that by discussing the backstories of artworks she hopes “to have opened up new ways of looking at Australian art” (p. 254). She has more than succeeded in doing just that. Unseen: Art and Crime in Australia is an important and welcomed addition to the growing canon of Art Crime texts.