Wednesday, May 28, 2014 -  Context Matters,david gill,Roman bronzes,So-Called Crosby Garrett Helmet,Spring 2014,the Journal of Art Crime

Context Matters,david gill,Roman bronzes,So-Called Crosby Garrett Helmet,Spring 2014,the Journal of Art Crime

No comments

No comments

Context Matters,david gill,Roman bronzes,So-Called Crosby Garrett Helmet,Spring 2014,the Journal of Art Crime

Context Matters,david gill,Roman bronzes,So-Called Crosby Garrett Helmet,Spring 2014,the Journal of Art Crime

No comments

No comments

David Gill on "The So-Called Crosby Garrett Helmet" in his column "Context Matters" for the Spring/Summer 2014 issue of ARCA's Journal of Art Crime

David Gill is Head of the Division of Humanities and Professor of Archaeological Heritage at University Campus Suffolk. He is a former Rome Scholar at the British School at Rome, and was a Sir James Knott Fellow at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. He was previously a member of the Department of Antiquities at the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, and a Reader in Mediterranean Archaeology at Swansea University (where he also chaired the university’s e-learning sub-committee). He is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and holder of the 2012 Archaeology Institute of America (AIA) Outstanding Public Service Award, and the 2012 SAFE Beacon Award.

David Gill

Context Matters

The So-Called Crosby Garrett Helmet

In late January 2014 a Roman bronze parade helmet went on display in the British Museum. It was said to have been found outside the small Cumbrian village of Crosby Garrett in north-west England. The helmet, now owned by an anonymous private collector, had previously been displayed at the Tullie House Museum in Carlisle (November 2013 to January 2014). The display in Carlisle was accompanied by a short illustrated booklet with contributions from a range of individuals (Breeze and Bishop 2013). Although the helmet reportedly surfaced within the last four years, a number of unanswered questions still remain.

The helmet itself is a good example of a “sports helmet” probably for use in the hippia gymnasia of a Roman cavalry unit (Bishop 2013). It appears to date from the late second or the third century AD (Bishop and Coulston 2013; Symonds 2014, 16). Three examples of “sports helmets” were found at the Roman fort of Newstead (Trimontium) in Scotland (Toynbee 1962, 166-67, pls. 104-106, nos. 98-100; Maxwell 2005, 63; Breeze 2006, 85, fig. 64). The Crosby Garrett helmet shared a case in the British Museum with the second century AD Roman parade helmet found as part of a hoard of metalwork at Ribchester, Lancashire in 1796 (Toynbee 1962, 167, pl. 108, no. 101).

The “Crosby Garrett” helmet is reported to have been found by one—though some reports suggested two—metal-detectorists from Peterlee in Co. Durham in May 2010 (on the east side of England). Peterlee is just under 80 km (50 miles) from Crosby Garrett as the crow flies. The helmet appears to have been “in 33 fragments, with 34 smaller fragments found in association” (quoted in Gill 2010a, 5). The site of the reported find was not shown to the Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs), Dot Boughton and Stuart Noon, of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) until August 30, 2010, more than three months after the discovery (Worrell 2010, 30). Noon recalls being shown the spot by the metal-detectorists who claimed it was “not a particularly rewarding area” (Symonds 2014, 13). This is in contrast to the recognised significance of the area in the study of the indigenous population during the period of Roman occupation (Higham and Jones 1985, 83-85). Boughton, the FLO for Lancashire and Cumbria, has now given a brief account of the “Discovery” (Boughton 2013). She supports the suggestion that there were two individuals, a father and son, present at the discovery. It should be noted that the first photographs of the helmet appear in the hands of a woman with manicured fingernails and wearing a striped jumper. It appears that helmet’s visor had been placed “face-down in the ground, and the back of the helmet broken off but folded and deposited inside the visor” (Boughton 2013, 17). There is the suggestion that if PAS officers had not confirmed the find-spot, then UK museums would not have been in a position to bid for the helmet when it had appeared at auction (Worrell et al. 2011).

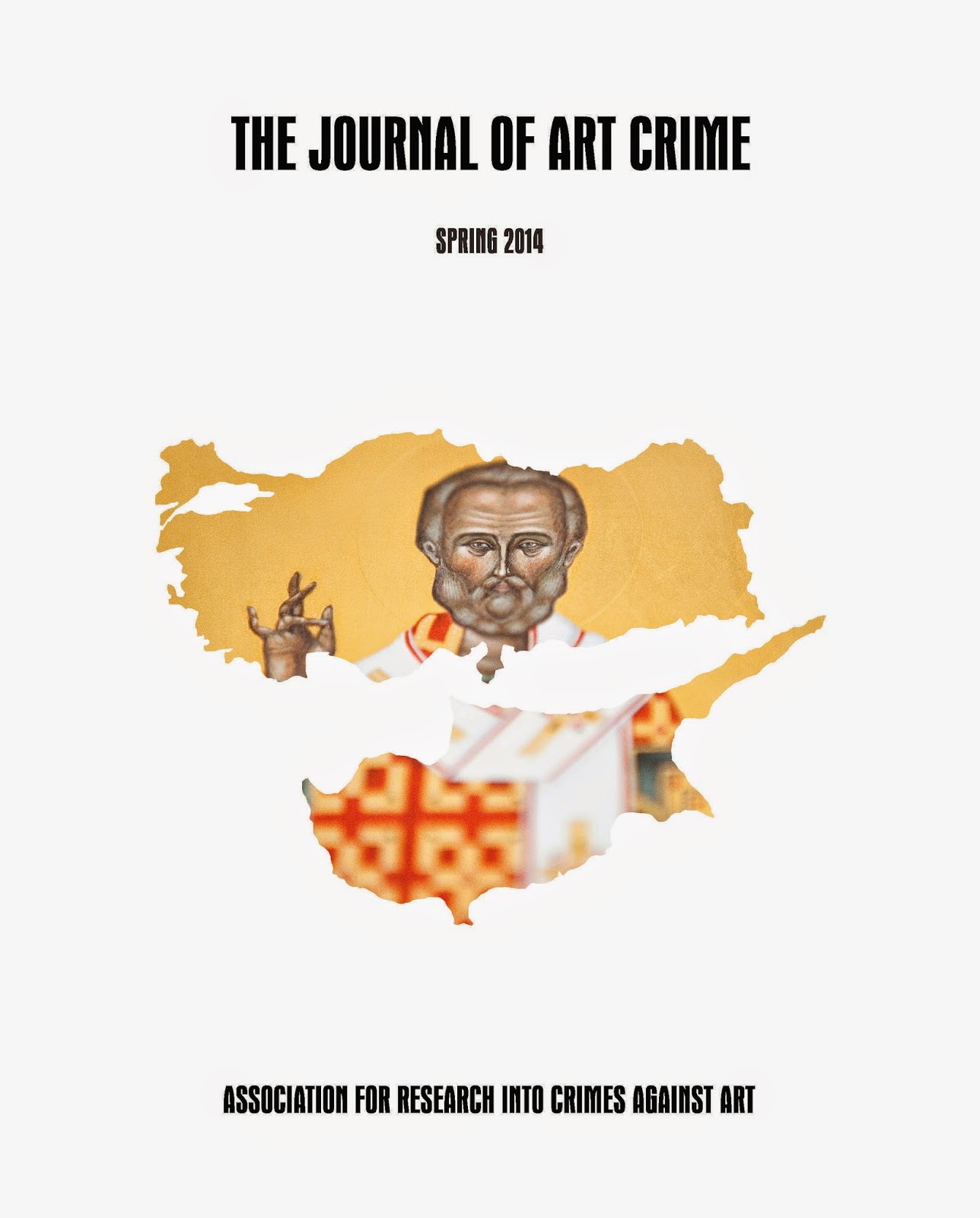

You may finish reading this article in the Spring/Summer 2014 issue (#11) of The Journal of Art Crime edited by ARCA founder Noah Charney. The Journal of Art Crime may be accessed through subscription or in paperback from Amazon.com. The Table of Contents is listed on ARCA's website here. The Associate Editors are Marc Balcells (John Jay College of Law) and Christos Tsirogiannis (University of Cambridge). Design and layout (including the front cover illustration) are produced by Urška Charney.