Given the recent interest in the July 31, 2017

article in the New York Times regarding the Python bell-krater depicting Dionysos with Thyros which was seized by New York authorities from New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, ARCA has elected to publish Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis' original

Journal of Art Crime article, in its entirety.

Originally published in the

Spring 2014 edition of the Journal of Art Crime, ARCA's publication is produced twice per year

and is available by subscription which helps to support the association's ongoing mission. Each edition of the JAC contains a mixture of peer-reviewed academic articles and editorials, from contributors authors knowledgeable in this sector.

We hope this article's publication will allow ARCA's regular blog readership and the general public to get a more comprehensive picture of this object's contentious origin.

Please note that Tsirogiannis' requested information from the Metropolitan Museum of Art on both the Bothmer's fund and the full collecting history of theis particular krater's recorded collection history on February 7, 2014, three years and five months before its present seizure by New York authorities. While the researcher did not say, at the time, that the vase had been identified in the Medici archive, given the focus of Tsirogiannis' research, it is safe to assume that the museum should have had an idea why this particular researcher may have expressed an interest in the vase's provenance and its acquisition via the Bothmer Fund.

----------

Nekyia

“A South Italian Bell-Krater by Python in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art”

In five images from the Medici archive appears a Paestan bell-krater depicting Dionysos with Thyros and phials. He is seated, along with a woman playing a double-flute with a bird on her lap, in a cart drawn by the god’s aged companion Papposilenos. Above Papposilenos appears the bust of a woman with a thyrsos, separated from the rest of the scene by a wavy line. Between this bust and Papposilenos, in direct visual alignment with the end of the flute played by the woman in the cart, appear the Greek letters *ΥΒΡΩΝ (*UBRŌN: the first letter is uncertain; only one roughly horizontal stroke survives, sloping slightly downward to the right at the level of the centre of the following Y). On the reverse side of the vase, two draped youths are depicted between palmettes identical to those that frame the main scene.

Four of the five Medici images are produced on regular photographic paper, and one is a Polaroid image. Two of the regular images are numbered in pen “4/50” and “4/51”, while the Polaroid is numbered “3/214”. The Polaroid image bears a handwritten note underneath: “H. cm 33,5 RΥΒΡΩΝ”. In all five images the krater is depicted intact, but half of the base and part of its rim are covered with soil or salt encrustations. The regular images present the krater standing on a dark red velvet surface. Also visible in these images is a creased brick-red paper stuck on a white surface leaning against the wall behind the vase; it seems that this is intended to complement the velvet base as a background.

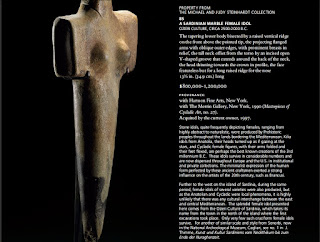

The same south-Italian bell-krater surfaced at a Sotheby’s antiquities auction on June 23, 1989 in New York. The consigner of the krater was not named in the auction catalogue and the object was offered as lot 196, under the general title “Other Properties”. No previous collecting history of the vase was mentioned in the catalogue. The estimation price given was $50,000-80,000. The catalogue entry reads:

Paestan Red-Figure Bell Krater, circa 360-350 B.C., painted with a phlyax scene depicting Dionysos and a Maenad seated in a cart pulled by the satyr Papposilenos, the nickname “Hubris” in Greek above him, Dionysos seated and holding a phiale and thrysos [sic], the maenad playing the double-flute, a dove perched on her lap, Papposilenos’ hairy body indicated by white dots, and wearing red anklets and leopard-skin, the bust of a maenad floating above holding a thrysos [sic], two draped youths in conversation on the reverse; details in added yellow, red, white, and brown wash. Diameter 14 1⁄2 in. (36.8 cm.)

Attributed to Python. Cf. Mayo, Art of South Italy, no. 106, and Trendall, Red-figured Vases of Paestum, pls. 92, 98, c-f, 99, 100, c-d, 101, e-f, 105, e-f, 107, a-b; also cf. pl. 89, for a vase by Python where Papposilenos is given another appropriate nickname.

The painter Python, and his colleague and probable teacher Asteas, were the most influential of the Paestan vase painters.

The object was sold for $90,000 (information received by email from Sotheby’s employee, Mr Andrew Gully on March 21, 2014).

Shortly after the Sotheby’s auction in New York, the vase became part of the antiquities collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (henceforth MET). It was given the accession number 1989.11.4. In the MET publication (Picon et al. 2007:239 no.184), the main scene on the obverse is described as follows:

The phlyax scene shows a youthful Dionysos, god of wine, and a flute-playing companion riding a wheeled couch. The draught is provided by an old silenos wearing a fleecy costume under a fawn skin. The inscription above his head reads “Hubris.” The drawing and polychromy, at once fluent and disciplined, represent Python at his best.

The MET website records that the acquisition was possible due to the “Bothmer Purchase Fund”.

A Tainted Collecting History

Following my previous articles for JAC (Tsirogiannis 2013a-b, discussing antiquities which passed through the hands of Medici), I need not describe at length the implications of the first signifcant fact; the vase appears in the archive of the convicted dealer Giacomo Medici, and no earlier collecting history can be found. It is, however, worth here applying a point made in The Medici Conspiracy on p. 57: the conditions of the photographs themselves confirm that this vase is very likely to have been excavated illegally after 1970 (the date of the UNESCO Convention against illicit trade in antiquities). The bell-krater is photographed using Polaroid technology not commercially available until after 1972; the krater is situated not in its archaeological context with a measuring tool, but with soil encrustations, on an armchair; in the regular photographs, the vase appears against a background whose brick-red colour seems clumsily matched with the dark red velvet surface, the same surface on which Medici photographed several other antiquities which later proved to be illicit and were repatriated to Italy (e.g. the 20 red-figure plates attributed to the Bryn Mawr Painter, once offered to the Getty Museum: see Watson & Todeschini 2007:95-98, 205; Silver 2010:138-139, 143). It is profoundly clear that the bell-krater was not in a professional environment or treated in a professional way.

Sotheby’s does not disclose the names of the consigners or the buyers of objects, as the company stated when contacted in the recent past while I was researching other cases of antiquities lacking collecting history (Tsirogiannis 2013a:7). Mr. Andrew Gully stated in January 2013: “Sotheby’s does not disclose the names of consigners or buyers. In the future, please use that answer as your guide” (email on behalf of Mr. Richard Keresey, Sotheby’s International Senior Director and Senior Vice President, Antiquities). However, the association between Sotheby’s and Medici has been described at length by Watson (1998:183-193) and Watson & Todeschini (2007:27). The first book led to the permanent closure of four departments of Sotheby’s in London, including the antiquities department; the second provides a detailed image of the continuous business between Sotheby’s and Medici during the 1980s.

The MET has a long history of acquiring looted and smuggled antiquities after the 1970 UNESCO Convention. The two most prominent cases were the Euphronios krater acquired in 1972 from the notorious dealer Robert Hecht during the directorship of Thomas Hoving, and the Morgantina treasure acquired in 1981, again from Hecht, during the directorship of Philippe de Montebello. On February 21, 2006, de Montebello signed an agreement in Rome to return both krater and treasure to Italy among 21 antiquities in total (Povoledo 2006). In January 2012, Italy announced the repatriation of c. 40 vase fragments from the MET; Fabio Isman revealed that the fragments matched vases already repatriated to Italy from North American museums, and noted that these fragments previously belonged to the private collection, kept in the MET, of the museum’s antiquities curator Dietrich von Bothmer (Italian Ministry of Culture 2012; Isman 2012).

This collection came to prominence again in 2013, when I matched a rhomboid tondo fragment of a kylix by the Euaion Painter at the Villa Giulia Museum in Rome to fragments from the Bothmer collection (Tsirogiannis & Gill forthcoming 2014). Although the MET did not reply to my email requesting the collecting history of the object (February 26, 2013), in July 2013 the Villa Giulia Museum informed me that the MET planned to return the rest of the kylix to Italy.

That match was made possible because the MET had posted (although they then withdrew) images of the fragmented kylix in the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Object Registry, a website on which museums can post objects lacking full collecting histories before 1970. The Registry covers only objects formally acquired by museums after 2008, which explains why the Python bell-krater does not appear there (last accessed on April 6, 2014). There is no such Registry for objects acquired in the period 1970-2008 and lacking earlier collecting history, but on the basis of this new identification and published reconstruction of the bell-krater’s collecting history, the MET should accept that this object too should be repatriated to Italy, either voluntarily, following the recent example of the Euaion kylix fragments, or, if it comes to court, following the United States vs. Frederick Schultz verdict, by which U.S. law recognized foreign patrimony law (Silver 2010:249; Renfrew 2010:94).

The Need for Further Academic Research

The identification of the vase in the Medici archive, with the handwritten note below the Polaroid image, not only suggests that the vase has most likely been unlawfully removed from Italian soil, but also highlights discrepancies between published interpretations of the main scene depicted on the vase. Let us look more closely at the scholarly descriptions of the vase to which the MET refers on its website.

The MET website gives three sources of publication for the vase; two from Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) and one from Carlos Picon et al. (2007) Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (no. 184, pp. 161, 439). The two references to LIMC turn out to be to the same paragraph, in the supplement to vol. 7, found at the end of vol. 8 (1997:1113, Silenoi no. 20a = “Tybron no. 2”). This reads:

New York, MM 1989.11.4 – Green 93 Abb4.4 - S. Tybron (oder Hybron) Zeiht Dionysos und Auletin auf einem Karren.

This description of the scene gives two readings of the writing on the vase, correctly noting that the final two letters appear to be Ω N (ŌΝ); the writing is interpreted as a nickname for the old Silenos figure, using the evidence of a neck-amphora attributed to Python (Trendall 1987: 142, pl.89 no.240) in which Papposilenos appears in the top right corner of an elaborate obverse scene (the birth of Helen from an egg) with the clear inscription ΤΥΒΡΩΝ above. Medici’s vase, it seems, was not known at the time of Trendall’s publication, since Trendall writes (p. 142): ‘this is the first time [‘papposilen inscribed ΤΥΒΡΩΝ’] has been identifed, though the name is not found elsewhere’. In LIMC, the inscription on the bell-krater is the second such identification but with some uncertainty about the reading (and hence, meaning) of the name.

The LIMC entry, describing Dionysos’ companion on the cart simply as ‘Auletin’, (‘flute-player’), is more neutral in description than the source it cites, John Richard Green in his book Theatre in Ancient Greek Society (1994). Green on p. 93 describes the scene on the krater (pictured in his fig. 4.4), ‘recently acquired’ by the MET, as that of ‘an actor as papposilenos’ pulling Dionysos and ‘Ariadne’ along on a cart (for Green, the bird on her lap is ‘doubtless...a symbol of love’) on a festive occasion, while ‘a maenad keeps them company’. By ‘maenad’ he means the thyrsos-bearing figure in the upper left corner of the scene, separated from the others by a wavy line. Green characterises the vase as “splendid”, referring to it as ‘by Python’, but placing it ‘on the earlier side of the painter’s career.’

There are a number of odd elements in this interpretation; in other vases attributed to Python, busts of figures appearing at the top of the scene, surrounded by a wavy line, are given names (inscriptions above the figures) indicating that they are deities or nymphs (e.g. the red-figured bell-kraters no. GR 1890.2-10.1 and 1917.1210.1 in the British Museum); that is, the wavy line in these cases represents a nimbus and hence the separation of realms. As for ‘Ariadne’, more is needed to support this mythological identification, which is not found in Picon; unlike several Python vases, there are no names on this krater except for the inscription, not mentioned by Green, at the level of the pipes above the Silenos-figure. Finally, Green’s dating of the vase to Python’s earlier period does not find support in the elaborate shape of the palmettes framing the scene, which, detached from the fans below the vase-handles, conform to the ‘standard variety’ rather than the less-developed earlier shapes (for a chronological overview, see Trendall 1987:16). The MET publication, unlike that of Green, refers to the vase as an example of ‘Python at his best.’

Green informs us in an end-note that the vase passed through Sotheby’s in New York, the same year (1989) it was acquired by the museum (Green 1994:192, note no. 8), a fact that is not stated on the MET website. Sotheby’s catalogue is in fact the earliest published attribution of the vase to Python, and the catalogue, although it cites Mayo and Trendall for parallels, does not in this case name the authority for the attribution (as it sometimes does in other cases). While the attribution to Python is most probably correct, the vase is not signed by Python; up to 1987, only two vases signed by Python were known (Trendall 1987:137, 139). It is odd that Sotheby’s cite a parallel in Trendall 1987 (‘another appropriate nickname’ for Silenos) and yet offer the incorrect reading of the inscription as ‘Hubris’, which in turn appears to be the basis for the official description on the MET website (last accessed April 2014) and published by the MET in Carlos Picon et al. (2007:439) (the third bibliographical reference given on the website). The MET too read ‘Hubris’, although citing LIMC, in which we find ‘Tybron (oder Hybron)’. Medici, for all his lack of Greek, did represent the inscription more accurately; the first letter seems to be a T or an H rather than an R, but the fading of the paint makes it uncertain. The ending of the word is more surely ΩΝ (ŌΝ); an abstract quality such as hubris is an unlikely inscription in this context.

It is evident from this outline of the different interpretations that further professional study is required.

We have highlighted both the partial nature of the collecting history given in all published sources, and the differences in the scholarly analyses of the vase. The fact that the MET’s bell krater – only the second vase on which papposilenos is given another name - is not included in Trendall’s 1987 corpus of Paestum vases indicates that the vase surfaced after 1987. However, Trendall’s 1987 reading of the neck-amphora inscription seems not to be exploited either in Sotheby’s reading of the inscription on the bell-krater in 1989 or the reading by Picon et al. in 2007.

Green alone mentions all the sources published at his time. Nevertheless, apart from this vase, there appear in Green’s book images of other vases that later turned out to be illicit (e.g. Green 1994:30, g. 2.9, an Attic red-figure calyx-krater with two members of a bird chorus about a piper, at the Getty Museum; Green 1994:46, g. 2.21, a Terentine red-figure bell-krater with comic scene showing a slave and two choregoi with a figure of Aigisthos, formerly in the Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman collection and, later, at the Getty museum); these were likewise depicted in Polaroid images from the Medici archive; they were repatriated to Italy (Godart, De Caro & Gavrili 2008:102-103 and 138-139, respectively).

The MET has several questions to answer. What is the ‘Bothmer Purchase Fund’? It has been proved that Dietrich von Bothmer played a crucial role in the acquisition of archaeological material, looted and smuggled after 1970, both on behalf of the MET and for his personal collection formed during the same period (Gill 2012:64; this obvious conflict of interest was overlooked by the museum; see Felch 2012, Tsirogiannis & Gill forthcoming 2014). My email to the MET (February 7, 2014), querying this point and requesting the full collecting history of the krater, remains unanswered, although it was sent to three different offices. No contact details for the Department of Greek and Roman Art are available on the museum website.

In a wider perspective, the Python bell-krater at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is one of many similar cases. North American museums, recently found to have acquired illicit antiquities, and forced to return those objects, still have in their possession many more. The very museums which advertise their care for transparency, in practice continue to conceal the full collecting history of tainted objects they own, and wait for them to be discovered. In this regard, the story of the Python bell-krater case is absolutely typical.

ARCA's publication is produced twice per year and is available by subscription which helps to support the association's ongoing mission. Each edition of the JAC contains a mixture of peer-reviewed academic articles and editorials, from contributors authors knowledgeable in this sector.

---------

Author's Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Dr. Helen Van Noorden for her comments and her overall help. My thanks go to Mr Andrew Gully (Sotheby’s) for providing me with the hammer price for the bell krater in the June 23, 1989 auction.

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

No comments

No comments

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

No comments

No comments