art copies,book review,Penelope Jackson

art copies,book review,Penelope Jackson

No comments

No comments

Penelope Jackson The Art of Copying Art

Penelope Jackson has done it again with The Art of Copying Art. This is a hard book to put down. She makes a strong case for the better appreciation of copies. She points out that copies tell their own stories, and add to our appreciation of the rich complexity and knowledge of art.

Her style of writing is appealing to non-art aficionados. She clearly states propositions and then relentlessly pursues the subject, presenting detailed evidence, allowing the material to speak for itself. Consequently, the reader has time to reflect on the permutations, and make up their mind. Typical of Jackson’s writing, she extensively footnotes her material, creating a rich resource for further investigation. Where questions remain, she frankly admits to this.

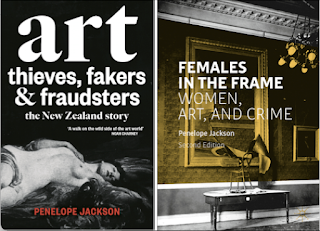

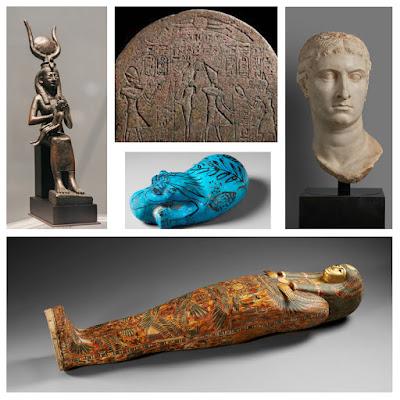

Jackson has a knack for choosing art related subjects that are little considered, bringing out fresh reflections and new perspectives. This is her third, general art “themed” book. The first, Art Thieves, Fakers and Fraudsters the New Zealand Story (Awa Press, 2016) was something of a trailblazer. She revealed largely unknown (even to New Zealanders) accounts of New Zealand art theft, reflective of international stories and trends. Her second book Females in the Frame Women, Art, and Crime (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) looked at the role of female actors in art crime, focusing on their often different intentions from male perpetrators. To my knowledge, this topic had not previously been explored. Indeed, I am aware that it has opened up fresh perspectives for study of female criminological behaviour.

How then, does her latest book add to this field? The Art of Copying Art again, is written for general consumption. Divided into nine chapters, each one is thematic. Chapter 1, “A Case for Copies”, makes the argument for studying copies. The following chapters then develop themes. Chapter 2 “Apprentice Artists”; chapter 3 “Copies for the Colonies”; chapter 4 “Paintings-Within-Paintings”; chapter 5 “Education and Entertainment”; chapter 6 “Copies in Public Collections”; chapter 7 “Protecting the Past”; chapter 8 “Cash for Copies”; and then a summation in the last chapter, “Afterword: Separating the Wheat from the Chaff”. The substantive part of the book is some 220 pages and amply illustrated.

We tend to forget, that prior to photography, scanning, and photocopies, the only way art could be known was through copies. Throughout history, many artists have only had access to signature artworks this way, lacking the visceral advantage of being exposed to the “real thing” in terms of context, quality, and scale. Thus, subsequent developments in art have been sometimes been affected by access to only inferior, or incomplete copies of signature works. I found chapter 3 particularly instructive. It explores the role played copies of artworks in the colonies, in terms of educating localised population to key works of art. Obviously some copies were better than others, and this led to the various developments discussed in the book. Chapter 4 is equally thought provoking. It discusses the extent to which lost masterpieces are only now known through copies, sometimes by being referenced in other artists’ paintings. A rich resource for art historians looking to scope, study, locate, and better appreciate those lost works!

|

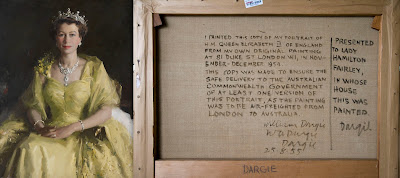

| Front and Verso of William Dargie's The Wattle Portrait (1954). Collection of National Museum of Australia, Canberra Image Credit: National Museum of Australia, Canberra |

Jackson makes the point that our current fixation with autograph, unique works, is a modern phenomenon (chapter 9). Painters sometimes operated workshops, reproducing their signature works for further distribution to collectors. Such copies were prized, often as equals to autograph works. It is only in more recent times that our mania for unique expression, and proved authenticity, has made copies seem somehow uninteresting, and second rate. Jackson points out even though this view prevails, the retention of copies remains important. What is a fake, forgery, or a mere copy, often rests on expert opinion. Whilst an institutional collector may recategorise a collected work as a copy, further study and science can reverse this judgment. Also, as Jackson argues that fakes and frauds also have a legitimate place. They remain a source of fascination and are necessary for historical context. An illustration of this this are van Meegeren’s fake Vermeers, that are now collectable in their own right Thus the destruction of fakes and forgeries (as presently dictated by the French State) comes at a cost. It not only risks destroying unproven authentic works, but damages our sense of art history. This is perhaps a point that requires more emphasis when we ponder on policing art crime.

It is a strength of this book that the content suggests further fields for consideration. With our present preoccupation fixation with authenticity, we tend to forget that masters’ copies of earlier artists’ masterpieces were often more valued (and valuable) than the historic original. This was under the belief that the later copy enabled the “genius” inherent in the earlier work to be further developed and interpreted. Especially, when it came to issues of developing original concept, or designo (entails fidelity to an original concept). Think Rubens’ copies of Titian, and (perhaps) Van Gogh’s copies of Delacroix and Millet. I would have welcomed such a more in depth discussion surrounding this issue. However, this is not a criticism. As Jackson herself would no doubt point out, she has had to contain her subject matter to some 220 pages.

I would strongly recommend this book for those interested in art, as well as those with a general interest in cultural history. The work is equally, if not more important, than her Females in the Frame. It makes a robust argument for the better appreciation of copies as a field of study, collection, and educated enjoyment.

Book Review by:

Rod ThomasAssociate Professor, Auckland University of Technology