Dutch penose,FATF,Jan-Dirk Paarlberg,money laundering,Organised Crime,Sotheby's

Dutch penose,FATF,Jan-Dirk Paarlberg,money laundering,Organised Crime,Sotheby's

No comments

No comments

When a money launderer's art collection comes up for auction

|

| Photo Credit ANP |

Once upon a time, the individual pictured above, Jan-Dirk Paarlberg had a prominent place in the Quote 500, with a fortune according to business publications that at its peak reached 280 million euros. A buyer and seller of works of art, his collection is said to have included works on canvas and paper by Marc Chagall, Claude Monet, Kees van Dongen, Pierre Bonnard, Karel Appel, Pablo Picasso, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, to name a few, as well a at least one sculpture, a statue by Feranando Botero.

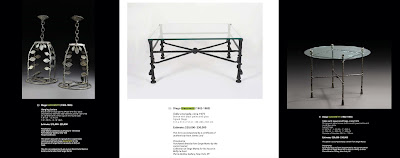

Forty-one objects from his collection have been consigned for auction and will be sold off today (and tomorrow) at Sotheby's Modern and Contemporary Art auction in Paris.

|

To show the interesting way the legal art market documents artwork ownership, shielding potential buyers from distasteful facts in publicly available auction records, its worth looking at one Paarlberg-owned painting. This hotly contested (for unrelated reasons) Portrait of Jeanne, c 1901, was painted by French impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Its sales advertisement makes no mention of Paarlberg in its provenance, only mentioning that the painting's last owner purchased the work from Kunsthandel Frans Jacobs in Amsterdam.

Instead this oil on canvas artwork, with a presales estimate of 500,000 - 700,000 EUR, lists an innocuous phrase in the text of the sale's page, which discretely states: Sale on behalf of the Dutch State.

But who is Jan-Dirk Paarlberg and why are his purchases and this upcoming sale interesting to ARCA?

Paarlberg was the man behind the Euromast in Rotterdam, the restaurants of the Oyster Group and the co-owner of the Merwede Group, which owns a large part of the retail properties in Amsterdam's PC Hooftstraat and on Rotterdam's Lijnbaan. He also had homes scattered in New York (at the historic Dakota), as well as in London, Portugal, and France, in addition to historic real estate in the Netherlands.

That is until the real estate magnate's empire collapsed.

Dutch authorities implicated Paarlberg in a money laundering scheme involving 17 million euros tied to the notorious Dutch penose underworld figure, Willem Frederik Holleeder. That legal entanglement marked a stark contrast to Paarlberg's previous stature, and underscores the intricate intersections of wealth, power, and criminal influence, and the art that we see in circulation in the art world. In this instance, it is not the art itself which is criminal, but the laundered money possibly used for its purchase.

Money, in part, it was determined by the courts, which had been extorted by Willem Holleeder from Willem Endstra. Another prominent Dutch real estate developer, known as the "banker of the underworld," Endstra was assassinated by hitmen in 2004. His death underscored the ruthlessness of Holleeder's organisation and its reign of terror, as well as Paarlberg's role in the perilous consequences of money laundering when it crosses paths with organised crime.

In testimony given on 19 April 2010, Jan-Dirk Paarlberg described some of his more suspicious art transactions. Speaking under oath, in the the Haarlem court, the former wealthy resident of the Maarssen castle Ridderhofstad Bolenstein described how he rounded up eight important artworks from his home, including the statue by Feranando Botero, a painting by Marc Chagall, a canvas by Claude Monet and five works by painter Kees van Dongen, and placed them all in his jeep before driving them to a Belgian dealer where he exchanged the objects for large denomination bills totalling of 8.5 million guilders (roughly 4.5 million euros).

Paarlberg was extremely vague on details, claiming he couldn't recall exactly which artworks he had sold, nor could he produce evidence of the pieces having ever been in his collection. He claimed he handed everything over to the dealer in Belgium for the new owner, having not saving purchase receipts, shipping documents, or even a single photograph which depicted the works which had once graced his properties.

Fourteen years ago, at the time of this testimony, Paarlberg's statements were met with skepticism. Art professionals argued about the feasibility of transporting a heavy Botero sculpture in his jeep, how Paarlberg had failed to use an art shipper, and even questioned the overly large cash sum he claimed to have been received as being excessive relative the value of the artworks and the two intermediaries. But given what we know about the underworld, and as “traditional” money laundering vehicles, such as real estate, became less attractive to criminals, (given their immovability) one has to wonder if this event could have gone down as the property baron described?

Fast forward to today. We now know and accept that art money laundering – often at inflated prices – to disguise the origins of illegally-obtained funds in order to reintroduce them into the legitimate economy, is in fact a thing. So much so that the FATF includes “cultural objects” in its sector-specific guidance as a potential vehicle to launder funds, or to finance organised crime, terrorist groups, or their related activities.

But none of this seems to be getting much coverage in Modern and Contemporary art market publications, nor with regards to today's sale, which, by the way, involves some 41 artworks seized by the Dutch authorities from Paarlberg's estate.

Who are the Penose?

While most of us have heard of Italy's 'Ndrangheta from Calabria, the Cosa Nostra from Sicily, and the Camorra based in Campania, few people outside of the Netherlands have heard of the Penose. Coming from Bargoens, a form of Dutch slang, the name is traditionally used to describe networks predominantly headed by ethnic Dutch crime lords, mostly known to operate in the underworld of Amsterdam, but also in other big cities in the Netherlands such as The Hague, Rotterdam or Eindhoven.

In addition to money laundering, members of the Penose have been associated with and convicted of activities such as drug trafficking, armed robbery, chop shops, illegal gambling, illegal slot machine vending, and, lest we forget, even contract killing.

To be clear, having been seized by the Dutch state, the proceeds from these upcoming auctions of Paarlberg's paintings won't support organised crime. But let them serve as an illustration that it is just as important to know who the names and backgrounds of former artwork owners are, as it is to know the names and backgrounds of the individuals who have sold work of art you are interested in.

Happy shopping, don't let the tricksters get ya.

By Lynda Albertson