Getty Bronze,Getty Museum,J. Paul Getty Museum,L'Atleta Vittorioso,Lisippo,Margherita Corrado,the Fano Athlete,Victorious Youth

Getty Bronze,Getty Museum,J. Paul Getty Museum,L'Atleta Vittorioso,Lisippo,Margherita Corrado,the Fano Athlete,Victorious Youth

No comments

No comments

An updated timeline on the history of the statue of the Victorious Youth: Comparing the Getty's last statements regarding the statue with the facts and with Italy's current political manoeuvring.

The JPGM's original timeline can [still] be downloaded here from the museum's website.

But before tackling the complexities related to the Getty's "right" to the ancient bronze statue known as "the Getty Bronze", it seems appropriate to remember the details of the imbroglio by examining essential phases of this antiquity's long story. As in the case with so many art restitution requests, situations are more complex than any one side of a story can tell.

History of the Statue referred to in Italy as L'Atleta di Fano, L'Atleta di Lisippo, L'Atleta Vittorioso, or for short, often as a point of pride, or affection, "il Lisippo."

According to statements taken by Fano fishermen with knowledge of the event, who worked aboard the fishing vessel Ferruccio Ferri and were involved in the discovery, the bronze statue, which came to be known as l'Atleta Vittorioso, was found by coincidence, and was hauled up into fishing nets from the Adriatic sea in August 1964. The captain of the vessel was Romeo Pirani, the owner of the vessel was Guido Ferri. Statements given by Pirani, Ferri and a deckhand aboard the vessel, referring to the approximate location where the statue was found, have at times been inconsistent. Also, the memory or capabilities of those making statements has also drawn questions as to abilities and motivations as we have pointed out in an earlier blog post.

In testimonies and statements given, the varying and conflicting distances which have been stated are:

- a few miles from the Fano coast, within Italian territorial waters. --as relayed by the testimony given by Renato Merli, an Imola merchant, on November 26, 1977 to the Italian Carabinieri. Merli reported to the Italian authorities that he had been told this distance directly by both Romeo Pirani and Guido Ferri, when approached about purchasing the statue in 1964. *Tribunale Ordinario di Pesaro, Criminal Section, Ufficio del Giudice per le indagini preliminary in funzione di Giudice dell’esecuzione, Ordinanza del 12 può 2009, n.2042/07 R.G.N.R. 3357/07 R.G.I.P. (It.)

- a few miles from the coast, within Italian territorial waters, where the fishing nets were thrown, in known shallow waters. --as told in the testimonies given by Romeo Pirani and Guido Ferri in December 1977 to the Italian Carabinieri. NOTE during his testimony, Pirani also admitted to his own role in the theft of this antiquity. By incriminating himself, his estimate could at least be considered reasonably honest. *Tribunale Ordinario di Pesaro, Criminal Section, Ufficio del Giudice per le indagini preliminary in funzione di Giudice dell’esecuzione, Ordinanza del 12 può 2009, n.2042/07 R.G.N.R. 3357/07 R.G.I.P. (It.)

- 32 (nautical) miles out from the Italian coast --as reported by Athos Rosato, a 15-year-old deckhand at the time the statue was lifted aboard ship, to US journalist, Jason Felch in an interview sometime in 2006.

- 43 miles from (Mount) Conero, a promontory situated directly south of the port of Ancona on the Adriatic Sea and about 27 miles from the coast of the former Yugoslavia at a depth of about 75 meters --as written by Judge Lorena Mussoni, preliminary investigation judge at the Tribunal of Pesaro, in her July 2007 order for confiscation of the bronze statue, which she based upon a statement made by the head of the fishing vessel. NOTE: This may have been during testimony given in the courtroom.

- 40 (nautical) miles out from the Italian coast --as told by Romeo Pirani to an Italian reporter for the Italian news publication Il Tirreno on November 20, 2007

- 37/38 miles from the port of Ancona, and 24/25 miles from Fano. --as stated in a video statement made by Athos Rosato, the 15-year-old deckhand at the time the statue was lifted aboard ship, published by the Italian news agency www.ilrestodelcarlino.it on December 4, 2018

It is important to note though, that determining the approximate distance from landfall as well as the direction, location and depth from which individuals have noted that this statue was pulled from the seabed, cannot be accurately ascertained simply by taking into consideration any of the testimonies or statements given to authorities or journalists. None of the documentation I have been able to review has specified whether or not the aforementioned distances, given by the fishermen aboard the Ferruccio Ferri, and in one instance drawn from a notebook submitted as evidence in which Romeo Pirani drew a map of the findspot, is it known if these stated distances were made utilizing instrumental or mathematical calculation or simply guestimates.

Without knowing if the vessel's estimated speed over elapsed time and course were factored in, also taking into consideration the effect of currents or wind on the vessel's trajectory on that day in 1964, it is impossible to ascertain, beyond a reasonable doubt, which, if any, of the findspot statements, might be truly accurate.

Findspot of the sunken statue, in international waters or not, notwithstanding, Greek presence in what is now the modern country of Italy began with the migrations of the Greek Diaspora from the 8th to the 5th century BCE and included various ancient Greek city-states in Sicily and the southern part of the Italian peninsula, an area referred to by the Romans as Magna Graecia (Latin: Greater Greece). But the Greek's expansion did not stop there.

|

| Map of Ancient Greece and the Ancient Greek Colonies Image Credit: wikimedia.org |

The political geography of the ancient world, in the region we know of today as Italy, did not follow the current boundaries applied to our modern country states. Nor were the Greek inhabitants of Le Marche isolated from the outside world. To classify the entire list of ancient peoples who resided on what is today called Italy, as either Roman or Italic, or by proxy to classify their cultural output as either Roman or Italian fails to consider the interconnectedness of all the peoples in antiquity, Greek and otherwise, who inhabited what is now known as Italy.

|

| Calyx by the Greek Potter Euphronios Museo Nazionale Archeologico Cerveteri, Italy Image Credit: ARCA |

By the same token, how would they classify the Riace Warriors, two full-sized Greek bronzes of naked bearded warriors, cast around 460–450 BCE which were found at sea by a diver near Riace on the southern coast of Italy in 1974? or the fact that

For that matter, how would the J. Paul Getty Museum classify the presence in Italy of the other works created by Lisippo di Sicione, the alleged sculptor of the Victorious Youth, whose seven other identified works are attributed to production in Magna Graecia (the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day regions of Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria and Sicily).

As for the JPGM's statement to the bronze's fleeting presence in Italy in modern times, it's worth mentioning that the introduction of the statue onto Italian territory was done so clandestinely, via two Italian vessels, the Ferruccio Ferri and the Gigliola Ferri, captained by Romeo Pirani and owned by Guido Ferri, in violation of the provisions set out in Articles 35, 36, 39, 42 , 48, 61 of Italian law n. 1089 of 1939.

Rather than declare the statue’s discovery to customs officials as required under Italy's law, the fishermen elected to hide the bronze from state authorities and to profit from its illegal sale. To protect their found treasure, they buried the bronze in a cabbage field at the home of Dario Felici, near Carrara di Fano before eventually selling it for a reported 3.500.000 Italian lire to the antiquarian Giacomo Barbetti. Barbetti in turn shifted the statue to his own property before moving it on to the church sacristy of Giovanni Nagni, a priest in Gubbio.

As the encrusted statue, covered in marine organisms and barnacles from its 2000 years in seawater began to smell, the ancient bronze drew unwanted attention. This forced the conspirators to again relocate the bronze, from under the stairs in the church's room for vestments, to the priest’s very own bathtub. There it was submerged in a saltwater bath to try and minimize the odour and slow its decay. Sometime thereafter it was shifted again, though to an unknown location.

All of the above actions demonstrate willful intent on the part of the fishermen smugglers and their intermediaries to profit from the illicit sale of this unregistered antiquity. It also illustrates the extent the actors went to, in order to willfully circumvent the Italian legislation's restriction on selling antiquities of this significance.

The Italian authorities received an anonymous tip about the existence of the statue in April 1965, involving a trip made by Giacomo Barbetti to Germany to find a buyer for the bronze. As a result of that lead, Italian law enforcement officers opened an investigation in May 1965 which focused on Giacomo Barbetti, his two relatives, Fabio and Pietro, and the priest from Gubbio, Giovanni Nagni. That same month, Italian authorities raided the home of Giovanni Nagni looking for the statue only to discover that the bronze had already been moved.

Some accounts state that Pietro Barbetti was the individual who removed the statue from the priest's home and who later sold it on to an unidentified individual in Milan. Other accounts state that Giacomo Barbetti sold the statue to an art dealer only a few days after its purchase from Mr. Ferri and Mr. Pirani (therefore in 1964) but here the dates and transactions are not very clear.

In 1966 these four accomplices were formally charged with purchasing and concealing stolen property in violation of Article 67 of Italian law n. 1089 of 1939.

On May 18, 1966 the judge at the Court of First Instance ruled for the acquittal of Barbetti, his two relatives, and Father Giovanni Nagni on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence for the government to make its case. Like a smoking gun without a corpse, without the whereabouts of the missing bronze statue, the court was left with insufficient evidence to determine if the underlying crime, that the bronze was of historical and artistic value, was in fact true, without that, they could neither prove that the statue existed or in which governing territory the antiquity had been found.

The sentences of acquittal at the tribunal level were subsequently challenged before the Attorney General at the Court of Appeal of Perugia and on January 27, 1967 where Italy's Appellate Court reversed the lower court's decision. In doing so, they convicted Barbetti and his relatives for receiving stolen goods. Nagni was convicted of aiding and abetting.

In turn, each of these convictions were then also appealed, this time by the defendants, to the court of final resort, Italy's Supreme Court, known as the Court of Cassation. This court annulled the Appellate Court sentence in May 1968 and ordered that the case be reheard at a new trial.

On November 8, 1970 the Court of Appeal in Rome absolved the four defendants of wrongdoing, as again, the whereabouts of the statue remained unknown, and without the benefit of being able to examine the unaccounted for antiquity, there was insufficient evidence to prove the underlying crime.

Interestingly, both Giacomo Barbetti and Giovanni Nagni both confirmed during court proceedings that they had purchased the bronze sculpture (in contravention of existing law) and sold the antiquity (in contravention of existing law) to an unnamed individual in Milan.

In the end, despite their lengthy nature, none of this first series of legal court cases against the four incriminated individuals resulted in convictions or provided the Italians with sufficient information to ascertain who the purported Milan buyer was, or where the statue had gone after leaving Gubbio.

It was simply gone, only to conveniently resurface, after the acquittal, in London in 1971.

While off the Italian radar, the statue of the "Victorious Youth" passed through a number of intermediary hands. After being smuggled out of Italy, the bronze crisscrossed its way through several countries including England and Brazil only to reappear again in documentation in the form of a document signed on June 9, 1971 where Établissement-Artemis is reported to have purchased an ancient statue from vendors in Brazil for $700,000.

Founded in 1970, and headed by German antiquities dealer Heinz Herzer, the evidence presented by the Italian state at the Tribunal in Pesaro in February 2010 suggested that Artemis was created ad hoc, with the specific purpose of managing the exportation, restoration and subsequent purchase of this valuable statue.

|

| Image Credit: NBC Documentary |

In a letter sent by Getty himself to Herzer on August 31, 1972, the billionaire asked the German dealer for documents related to the earlier Italian trials on the 4 accomplices. He also asked for all the documentation Herzer had surrounding the statue's acquisition.

A note signed by Norris Bramblett, longtime personal aide to Mr. Getty and Treasurer of the J. Paul Getty Museum, reads: "Mr. Getty said that, subject to obtaining the undisputed title of property and supposing to be able to obtain it, to the satisfaction of Attorney Stuart Peeler, (the lawyer for the Museum), he would recommend to the trustees to purchase the statue ." ** Tribunale Ordinario di Pesaro, Ufficio del Giudice per le indagini preliminary in funzione di Giudice dell’esecuzione, Ordinanza del 12 può 2009, n.2042/07 R.G.N.R. 3357/07 R.G.I.P. (It.)

The time period it took for this "robust" review by Peeler is not stated in the Getty's timeline, but according to court documents, a letter was sent to Stuart T. Peeler on 4 October 1972, by lawyers Vittorio Grimaldi and Gianni Manca of the Ercole Graziadei law firm, which represented Herzer and the art firm Artemis. In the attorneys' opinion "on the question of the Greek bronze" the two Italians affirmed that the statue had been purchased by one of their clients (Établissement pour la Diffusion et la Connaissance des Oeuvres d'Art "DC") in Brazil by a group of Italian sellers on 9 June 1971. (This letter is part of Annex 10 of the defence evidentiary documents of December 21, 2009).

This event can also be corroborated via statements made by David Carritt who reported to the British police that the bronze had been purchased from a division of the Artemis firm referred to as the "Établissement DC", based in Vaduz in Liechtenstein.

Grimaldi and Manca both reported that the bronze had been the subject of an investigation and trial in Italy, which began in 1965 and which concluded in 1970, with a definitive sentence of acquittal delivered by the Court of Appeal of Rome. It is interesting to note that the lawyers also clarified that the acquittal had been determined by the lack of ascertaining both, the place of the statue's discovery, and the uncertainty about the nature of the good's archaeological or historical interest to the state. **Tribunale Ordinario di Pesaro, Ufficio del Giudice per le indagini preliminary in funzione di Giudice dell’esecuzione, Ordinanza del 12 può 2009, n.2042/07 R.G.N.R. 3357/07 R.G.I.P. (It.)

Stuart T. Peeler and his father were J. Paul Getty private lawyers and according to his own obituary was responsible for the judicial process whereby Getty's will was "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document, as well as managing the Getty Trust's general activities abroad. Peeler was also an executive of Santa Fe International Oil. Given that, Getty left an estate worth nearly $700 million to the J. Paul Getty Museum Trust and that the Trust was required to spend 4.25 % of the average market value of its endowment per year, I suspect the time Peeler spent examining this statue's ethics was minimal at best, in relation to the other affairs he was tasked with.

It was in Hertzer's studio in Munich on December 13, 1972 that the bronze was first examined, by Dr. Thomas Hoving, then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. According to statements Hoving made, in a news documentary produced by ABC News of Los Angeles on the Getty Museum's important acquisition, Hertzer had originally offered to sell the ancient statue to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $4.4 million, a figure which superseded the New York museum's budget.

Initial talks began via a phone call between Hoving and Getty, regarding a possible joint ownership scheme between the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, funded primarily by John Paul Getty. The pair later met in London on June 14 1973. On that occasion, Hoving received approval from Getty to negotiate a 3.5 million dollar asking price with Herzer and Artemis, with a tentative agreement being made between the two men that the bronze would be shared between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum in exchange for the Met providing a long term loan to the J. Paul Getty Museum of its 17 Boscotrecase frescoes.

Evidence presented by the Italian state at the Tribunal in Pesaro in February 2010 related that John Paul Getty was therefore fully aware of the criminal proceeding which had been brought by the Italian AG against the accomplices involved in the smuggling of the bronze. Also, to finalize the potential deal, John Paul Getty demanded the original title owned by Herzer, as well as to ascertain or negate the existence of any right to ownership from the Italian State, including all details on the methods of exit of the property from Italy and the existence or otherwise of the jurisdiction of the Italian State.

When Hoving returned to New York, he immediately contacted the members of the Met's Acquisitions Commission in order to agree upon the modalities of a formal joint acquisition agreement for the antiquity and to work out the written details of said agreement. Dietrich von Bothmer (a member of the Met's Acquisition Commission) completed the Lisippo acquisition form containing all the relevant details for the proposed deal. At point XII of this purchase form von Bothmer stated that he had learned of the existence of the ancient bronze via Elie Borowski, a prominent antiquities dealer who himself is an individual of controversy. Borowski had told von Bothmer that he had witnessed seeing the statue while it was still hidden inside the bathtub at the priest's residence in Gubbio.

On June 25, 1973 Hoving hand-delivered a letter to David Carritt, the negotiator designated by Artemis for the potential sale informing the firm that he had been authorized by John Paul Getty to offer the sum of $ 3.8 million for the purchase of the bronze. In this letter Hoving stated:

"As I made clear in our conversations, (that you had previously heard by telephone) the conclusion of this purchase by Mr. Getty is subject to examination and approval of the Council of the Metropolitan Museum and of Mr. Getty's Legal Advisor, in relation to certain legal issues that may require qualifications or certifications ... "In the days that passed the negotiated figure for the purchase of the statue changed several times; raised on the part of Hertzer through Carritt or negotiated lower by Getty, but always without the substantiating documentation requested by the two museums being produced.

On November 3, 1973 Herzer wrote to Jiri Frel, curator of antiquities at the J.Paul Getty Museum from 1973 until 1984, to announce the failure of the negotiations to achieve an agreeable selling price among all parties for the joint acquisition of the statue between the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum.

In 1973 the Carabinieri TPC acquired a lead that a bronze sculpture attributed to Lysippos and coming from Italy, was in the Heinz Herzer antiquities shop in Munich. Following up on the lead, the Carabinieri visited Herzer's shop in July 1973 when they were in Munich for another investigation. Herzer was not present when the officers arrived, only his secretary and his lawyer were. They confirmed that Herzer was in possession of the statue in question, and claiming that Herzer was in possession of documentation proving the lawfulness of the statue on the art market. At the time of the visit, the lawyer refused to deliver any photographic imagery, detailing the bronze.

On January 9, 1974 the Italian Magistrate in Gubbio opened a court proceeding against unknown persons for the crime of clandestine exportation and issued an international rogatory request asking for the seizure of the sculpture, as well as an interrogation of Herzer as a suspect potentially involved in the clandestine exportation of archaeological finds from Italy. The request also asked for any photographic documentation Herzer might have of the statue.

It should be noted that up until that date neither the German authorities nor the Italian authorities had acquired any photographs of the trafficked artwork in its original state, having just been raised from the sea. This would be a critical piece of evidence, necessary for the authorities in both countries to compare and ascertain whether the plundered antiquity from the Adriatic was the same as the restored bronze now in Herzer's possession.

Court documents and statements made by Jiri Frel show that in 1975 John Paul Getty, showed at least some continuing interest in the bronze statue, where, upon his request, the antiquity was shipped for a second time to the London warehouses of David Carritt Ltd., a branch of the Artemis SA, established in Luxembourg.

John Paul Getty Sr. died of congestive heart failure on June 6, 1976.

One year after his death, and without the relevant supporting documents originally required by John Paul Getty in furtherance of this acquisition, the J. Paul Getty Museum went ahead with the statue's purchase. The antiquity was acquired in the United Kingdom on August 2, 1977 via an invoice issued by David Carritt Ltd., in its capacity as Agent of Établissement D.C. The purchase price was $3.95 million.

This is not the factually correct basis for the German court's ruling, as has already been outlined earlier in this blog post.

Italy's Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali (ENGLISH: The Ministry for Cultural and Environmental Heritage) has gone through several name changes through differing elected Italian governments. The reason for the ministry's failure to join any of the Italian legal proceedings related to the bronze in the 1960s stems simply from the fact that the ministry did not yet exist as it was not until 1974 that the ministry was formally established.

Set up by the Moro IV Cabinet through a December 14, 1974 decree, n. 657, the newly formed Italy's Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali (defined as "per i beni culturali" - that is for cultural assets) took over the heritage remit and functions previously found under the Ministry of Public Education (specifically its Antiquity and Fine Arts, and Academies division).

The date of this statement, and who it was made to, and in what, if any, official capacity has not been clarified in the Getty Museum's timeline. In 1967 Luigi Salerno was appointed to be the director of the Fondazione della Calcografia Nazionale. At or near this same date he was also made a director at Rome's Ufficio esportazione. It is important to note that there are Uffici di Esportazione Oggetti d'Antichità e d'Arte in many Italian cities, each with their own directors. In 1973 Salerno left his Rome positions to become Soprintendenza dell'Aquila, retiring early from his administrative responsibilities to devote more of his time to his writing and research. As this is the same year in which John Paul Getty became interested in the bronze, it can be assumed that his recommendations were made solely in an unofficial capacity.

In Magistrate Gasperini's own June 2018 order of forfeiture, the judge mentions Salerno in the following passage:

A logical similar argument, equally effective in lieu of consulting this non-existing registrar, could have been that to request a direct ruling to the Italian Ministry of Cultural Goods, which the lawyers of the seller, as well as Paul Getty and so, at last, also the members of the Board of Trustees always failed to file, while lying down on the unofficial discussions held (in the firm of the professional) by Mr. Grimaldi with an official of the Ministry, Mr. Salerno, who had contacted him to verify whether there had been any negligence by the Italian Ministerial authorities. In that occasion, lying, Mr. Grimaldi said to Mr. Salerno that the statue originated from Greece. (the information is contained in the letter sent by Mr. Grimaldi to Mr. Brownell dated l.10.1973)

Despite the lack of legal provenance documentation or export certificates substantiating the antiquity's legitimate export out of any originating source country where Greek remains might be found, and superseding the voiced concerns of the statue's legitimacy raised by John Paul Getty himself.

As stated above, the Court of Cassation annulled the Appellate Court sentence in May 1968 and ordered the case reheard in a new trial. On November 8, 1970 the Court of Appeal in Rome absolved all four defendants of wrongdoing, as again, the whereabouts of the statue was not known at that time and without the benefit of being able to examine the unaccounted for antiquity, there was insufficient evidence to prove the underlying crime that the bronze was of historical and artistic value or in which governing territory the missing bronze had been found.

On November 25, 1977, the Embassy of Italy in London contacted officials in Italy and relayed that the director of the London gallery Artemis had specified that the lawyers Graziadei and Manca (lawyers of Artemis) had obtained a regular bronze export license for the object's transfer. A cross-check was begun by the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Artistic Heritage on January 2, 1978 who then sent a photograph of the statue of Lysippos to the Ministry for Cultural and Environmental Heritage, and from there on to the country's Export Offices in order to ascertain if an export license had ever been requested from any of them.

While taking many months to conclude, on May 23, 1978, the Central Office for Environmental, Architectural, Archaeological, Artistic and Historical Heritage of the Ministry for Cultural and Environmental Heritage reported that no license of export, for the bronze statue, had ever been issued by the Italian authorities.

In September 2007 Italy announced that it had agreed to drop its civil lawsuit against Marion True, the former curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum after the Los Angeles museum signed a formal joint agreement to return a total of 40 antiquities plundered from Italian territory.

Thirty-nine of the antiquities covered by the deal were scheduled to be transferred to Italy by the closure of 2007. The 5th century BCE cult statue of a Goddess sometimes referred to as the goddess Aphrodite, would remain at the California museum through 2010. In turn, Italy agreed to loan other works to the J. Paul Getty Museum which were not looted in origin.

The Objects to be Transferred to the Italian State, identified as tied to known traffickers, was as follows:

1. Cult Statue of a Goddess, perhaps Aphrodite - 88.AA.76

2. Askos in Shape of a Siren – 92.AC.5

3. Fresco Fragments – 71.AG.111

4. Lekanis – 85.AA.107

5. Two Griffins Attacking a Fallen Doe – 85.AA.106

6. Attic Red-Figured Neck Amphora – 84.AE.63

7. Fragment of a fresco: lunette with mask of Hercules – 96.AG.171

8. Apulian Red-Figured Pelike – 87.AE.23

9. Apulian Red-Figured Loutrophorus – 84.AE.996

10. Attic Black-Figured Zone Cup – 87.AE.22

11. Attic Red-Figured Kalpis – 85.AE.316

12. Attic Red-Figured Kylix – 84.AE.569

13. Apulian Pelike with Arms of Achilles – 86.AE.611

14. Attic Red-Figured Kylix – 83.AE.287

15. Attic Red-Figured Calyx Krater – 88.AE.66

16. Attic Janiform Kantharos – 83.AE.218

17. Attic Red-Figured Phiale Fragments by Douris – 81.AE.213

18. Marble Bust of a Man – 85.AA.265

19. Attic Red-Figured Amphora with Lid – 79.AE.139

20. Apulian Red-Figured Volute Krater – 85.AE.102

21. Attic Red-Figured Calyx Krater – 92.AE.6 and 96.AE.335

22. Attic Red-Figured Mask Kantharos – 85.AE.263

23. Etruscan Red-Figured Plastic Duck Askos – 83.AE.203

24. Statue of Apollo – 85.AA.108

25. Group of Attic Red-Figured Calyx Krater Fragments (Berlin Painter, Kleophrades Painter) – 77.AE.5

26. Apulian Red-Figured Bell Krater – 96.AE.29

27. Statuette of Tyche – 96.AA.49

28. Attic Black-Figured Amphora (Painter of Berlin 1686) – 96.AE.92

29. Attic Black-Figured Amphora – 96.AE.93

30. Attic Red-Figured Cup – 96.AE.97

31. Pontic Amphora – 96.AE.139

32. Antefix in the Form of a Maenad and Silenos Dancing – 96.AD.33

33. Bronze Mirror with Relief-Decorated Cover – 96.AC.132

34. Attic Red-Figured Bell Krater – 81.AE.149

35. Apulian Red-Figured Volute Krater – 77.AE.14

36. Statuette of Dionysos – 96.AA.211

37. Attic Red-Figured Calyx Krater (“Birds”) – 82.AE.83

38. Group of three Fragmentary Corinthian Olpai – 81.AE.197

39. Paestan Squat Lekythos – 96.AE.119

40. Apulian Red-Figured Volute Krater – 77.AE.13

At the time of the joint agreement, both parties agreed to defer further discussions on the Statue of a Victorious Youth until the outcome of its legal proceedings.

Prior to the aforementioned signed accord then Minister of Culture Francesco Rutelli stated the following.

Italian: ''Vorremmo fare il punto sul rapporto con il Paul Getty Museum perché ci sono state alcune incomprensioni, mentre vorremmo che fosse molto chiara la nostra posizione: infatti, esiste una serie di provvedimenti giudiziari che hanno i loro corsi e, mentre la magistratura svolge i propri accertamenti, vorremmo trovare una soluzione di buona volontà con il Getty''.

English" We would like to take stock of the relationship with the Paul Getty Museum because there have been some misunderstandings, while we would like it to be very clear on our position: in fact, there are a number of judicial measures that have to run their courses and, while the judiciary conducts its investigations, we would like to find a solution of good will with the Getty ''Rutelli's statement is in keeping with Italy's soft diplomacy approach of voluntary forfeiture, a negotiative strategy which is designed, not to strip a museum bare of its contested objects when they have been determined to have been looted, but to undertake a collaborative approach with museum administration in furtherance of "goodwill" and where long term loans can be made of alternative objects of know licit origin as part of those accords.

Putting its own public pressure on the J. Paul Getty Museum, on April 4, 2007, the cultural association 'Le Cento Citta' presented a complaint via the Public Prosecutor at the Tribunal of Pesaro for violation of customs regulations and for smuggling in relation to the theft of the bronze. This time, armed with the photographic evidence provided to the Carabinieri by Renato Merli on November 24, 1977, which showed the bronze statue as it appeared at the time of its discovery, still covered with marine life, Italian prosecutors finally had a body to go with their smoking gun as Merli's photo perfectly matched the statue sold by Artemis to the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Putting its own public pressure on the J. Paul Getty Museum, on April 4, 2007, the cultural association 'Le Cento Citta' presented a complaint via the Public Prosecutor at the Tribunal of Pesaro for violation of customs regulations and for smuggling in relation to the theft of the bronze. This time, armed with the photographic evidence provided to the Carabinieri by Renato Merli on November 24, 1977, which showed the bronze statue as it appeared at the time of its discovery, still covered with marine life, Italian prosecutors finally had a body to go with their smoking gun as Merli's photo perfectly matched the statue sold by Artemis to the J. Paul Getty Museum. As was the case with the earlier court proceedings the new Pesaro case dragged on for years within the Italian court system, with numerous reversals of verdicts and also noting the deaths of many of the original illegal actors.

Dismissed by the Lower Court in 2007, the decision was appealed by the Public Prosecutor with the support of Italy's Avvocatura dello Stato, and on 12 June 2009 the new magistrate Lorena Mussoni, preliminary investigation judge at the Tribunal of Pesaro ordered the forfeiture of the statue on the basis of the fact that the object had been exported out of the Italian territory in contravention of Italian laws.

The case heavily focused on the Italian Navigation Code, and the fact that Italian flagged fishing vessels, even if in international waters were by extension owned by Italy and the fact that the fishermen intentionally failed to report the statue's presence once it arrived onshore in Italy. It also relied on the fact that the bronze had been smuggled illegally out of Italy without a license for export.

In her June 12, 2009 order for seizure Mussoni acknowledged that the statue's findspot was contested but she based her ruling, in part, on the fact that Italy nevertheless owned the statue ab initio under Italian patrimony laws as article 4, second paragraph of the criminal code, defined the fishing vessel as the territory of the State for fictio juris, as Italian ships and aircraft are considered as the territory of the State wherever they are, unless they are subject, according to international law, or to foreign territorial law.

"serious negligence and the consequent link between the current holder of the asset and the offense in charge of heading a) of the heading, which does not permit the qualification of the Museum "person unrelated to the offense" pursuant to article 174, paragraph 3 of Legislative Decree no. 42/2004."

The J. Paul Getty Museum subsequently challenged Judge Lorena Mussoni's order of forfeiture before the Italian Court of Cassation on February 18, 2011. At that hearing, the case was remanded back to the Tribunal of Pesaro for further examination of the merits of the case.

On May 3, 2012, Maurizio Di Palma, the Pre-Trial judge at the Tribunal of Pesaro, once again upheld the earlier 2010 order of forfeiture and confirmed that the statue was illegally exported from Italy. His ruling placed the case's resolution back with Italy's Supreme Court for what was supposed to have been the Higher Court's final ruling.

In February 2014 Italy's highest court elected not to issue any ruling upholding or rejecting the lower court's judgment that the "Victorious Youth" was illicitly exported from Italy and as such, is subject to seizure. Instead, the Prima sezione penale della Cassazione (First Penal Section of the Supreme Court of Italy) elected to transfer the case to the Terzo sezione penale della Suprema Corte (Third Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court) where a new hearing was scheduled to establish whether or not the order of confiscation issued by the Court of Pesaro on May 3, 2012 should be affirmed.

Squashing the decision made by the Court of Pesaro on May 5, 2012, the Terzo sezione penale della Suprema Corte (Third Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court) on June 4, 2014 remanded the case back to the Tribunal in Pesaro for a new opposition procedure, granting the Getty's request for the case to be heard in open court.

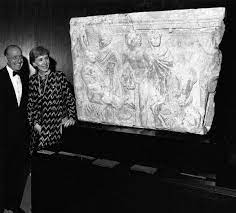

|

| Judge Gasparini listens to Getty council’s final argument in open court Pesaro court house, 05 Feb 2018 Image Credit: ARCA |

This series of hearings eventually concluded on February 5, 2018.

On June 08, 2018, in a long-awaited judicial decision, four full months after the Pesaro open court hearings had concluded, Italy's Court of First Instance, the Tribunale di Pesaro issued a lengthy 46-page ordinance, written and signed by Magistrate Giacomo Gasparini firmly rejecting the Getty museum's opposition to Italy's order of confiscation on the grounds of Articles 666, 667, and 676 of the Italian Criminal Code, article 174 section three of the Legislative Decree no. 42 of 2004 and article 301 of Presidential Decree. 15 of 1972. In turn, Gasperini affirmed the order of forfeiture for the statue known as the "Victorious Youth," attributable to the Greek sculptor Lysippos, as previously ordered on February 10, 2010.

Appealed to the higher court again, on December 3, 2018, Italy’s Cassation Court rejected the J. Paul Getty Museum's appeal against the lower court ruling in Pesaro, issued by Magistrate Giacomo Gasparini.

Saying anything more here will make this already very long post unnecessarily redundant.

In 1983 the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) became law in the United States, implementing the 1970 UNESCO Convention. This Act provides the legal framework for bilateral agreements that combat looting.

Additionally, the United States National Stolen Property Act of 1934 (NSPA) (18 U.S.C. §§ 2314 et seq.) prohibits the transportation in interstate or foreign commerce of any goods with a value of $5,000 or more with the knowledge that they were illegally obtained and prohibits the "fencing" of such goods. The NSPA also allows foreign countries’ cultural patrimony legislation to be effectively enforced, within very specific circumstances, within U.S. territory by U.S. courts. These patrimony laws generally consider theft to include the unauthorized excavation or removal of artefacts from their archaeological context in the country of origin.

Ultimately, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has investigative jurisdiction for stolen property offences as set forth in the NSPA. The Office of Enforcement Operations of the Criminal Division has supervisory responsibility over offences arising under 18 U.S.C. §§ 2314 and 2315. It should be noted that the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) of 1983 provides civil remedies while the NSPA provides criminal sanctions.

For the Italians to win in the US, the bronze must be considered stolen in the United States. Additionally, Italy's attorneys would need the US courts to agree that the statue was discovered within the Italian territories and that Italy's cultural patrimony law unequivocally vests ownership of such antiquities to the State.

Partially correct, as mentioned early in this post, at the time of the original hearings the Italians were lacking any photographic evidence tying the statue fished from the sea and taken onshore in Fano to the antiquity later on sale, first in Germany and later in the UK via Artemis. The rest of the statements in the Getty's above paragraph have already been elaborated upon.

That will ultimately be up to the US Courts to decide, assuming the J. Paul Getty Museum wants to continue this argument in the United States' jurisdiction and assuming the Italians press for such via an ILOR.

Interesting in theory, but realistically solely conjecture as again, the purported location of where the statue was fished has never been fully clarified. For now, the Italian Court at the Tribunal level in Pesaro, the Court of Appeals and the Court of Cassation have all ruled (in some cases repeatedly) in favour of seizure based upon Italian current laws.

In common law jurisdictions, such as the UK or the United States, a thief cannot transfer good title to stolen property. This means that each time the statue changed hands, it still remained tainted to all subsequent possessors. California law specifically recognizes that “each time stolen property is transferred to a new possessor, a new tort or act of conversion has occurred,” and so the statute of limitations begins to run again with each subsequent good or bad faith buyer.

This point may be mute however given the statue has been in the possession of the Getty Museum since 1977, a period of time greater than that allowed by California's statute of limitations, in part because Italy and the Getty both agreed to allow the course to run its course in Italy before picking up discussions, on the statue's potential restitution.

And so I suspect shall the Italians. In court or out.

Frankly speaking whether or not the museum is ultimately obliged judicially to return the bronze to Italy, its ethical quandary, of maintaining a plundered object in its collection in spite of its known illicit nature at this point is just plain old contrariness.

Clinging to this antiquity despite its tainted pedigree seems a little misguided. Doing so creates further ill will with an important source country and its judiciary is not prudent for that relationship. It also diminishes the stature of the museum in the eyes of scholars and the knowledgeable public as an ethical collecting institution.

To read all of ARCA's posts on the Getty case, follow our link here.

By: Lynda Albertson