Michael Steinhardt has a long standing record of making astute financial decisions, many of which have led to stellar investment performance earnings totalling in the millions on Wall Street. Unfortunately his culture capital record: for making careful, sound, and informed decisions when purchasing antiquities for his purported $200 million private collection of art, has been anything but stellar.

As Master of the Hedge Fund Universe, Steinhardt has the liquidity to be choosy about his art purchases. With a current net worth of $1.05 billion, according to a 2017 article in Forbes Magazine, and almost thirty years of collecting experience, he's also a member of Christie’s advisory board. Tight with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he has had a Greek Art of the Sixth Century B.C. gallery named after him at the museum. All that to say Steinhardt should be sufficiently well informed about the social and ethical obligations of responsibly acquiring, managing and disposing of items in his burgeoning art collection.

So why then, with access to so many of the art world's elite, has he chosen to overlook the importance of provenience (country of origin) and provenance (history of ownership) of the objects he fancied BEFORE allowing them to enter or exit his collection and comparing that information within the context of the US and international legal frameworks and abiding accordingly?

I guess traders love to gamble (more on that later) a fortune on their compulsions.

Some of Steinhardt's costly gambles:

A fourth century BCE gold phiale

The high court found no compelling reason to rehear Steinhardt's case on the basis that the importer had intentionally undervalued the object's worth, transited the object illegally from Sicily to Switzerland, and provided false statements misrepresenting the phiale's country of origin on the objects import documentation.

The two antiquities dealers involved in the purchase, Robert Haber and William Veres, were each given suspended sentences of one year and ten months imprisonment. The extent of Steinhardt's culpability though was left vague in the final court filings. Yet Steinhardt's experience as an art collector and specifically his experience with Haber, with whom he had already purchased some $4-6 million in art objects, raises considerable doubts as to his naïveté.

The fact that the bill of sale from Haber to Steinhardt's even stipulated that if "the object is confiscated or impounded by customs agents or a claim is made by any country or governmental agency whatsoever, full compensation will be made immediately to the purchaser" gives the impression that both the collector and his dealer were aware of the potential for illegality in the market, and possibly with this object specifically.

(Il)licit Excavations of Maresha Subterranean Complex 57:

The ‘Heliodorus’ Cave

In early 2007 Michael Steinhardt acquired the so-called Heliodorus Stele from Gil Chaya, an antiquities dealers in Jerusalem, who is reportedly a nephew of the late Shlomo Moussaieff. Moussaieff once owned one of the largest collections of biblical antiquities, many of which were unprovenanced. After the purchase Steinhardt and his wife presented the stele to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem on an extended loan.

The stele contains a magnificent 2nd century BCE Greek inscription which documents a correspondence between the Seleucid king, Seleucus IV (brother of Antiochus IV) to an aide named Heliodorus. Unsurprisingly though, the bottom portion of the stele was missing, leaving a gap in scholarship as well as a tell-tale signature that the stele had likely been looted upon its extraction, since its base was missing.

Earlier, during 2005 and 2006 excavations at the Maresha Subterranean Complex 57 at Beit Guvrin National Park three fragments were uncovered that were subsequently identified as matching the bottom of Steinhardt's stele. These fragments were discovered in a subterranean complex by participants in the Archaeological Seminars Institute's "Dig for a Day" program. The correlation of the fragments' epigraphy and testing of their stone and soil samples at the find site proved that the fragments were a perfect match, completing missing pieces of the stele.

It was later determined that the stele

had been stolen during a robbery at the Beit Guvrin National Park in 2005. Tel Maresha's head archaeologist, Dr. Ian Stern verified that he remembered arriving at the site on a Sunday morning in 2005 only to find that the cave where the fragments were later found, had been “turned upside down,” apparently by looters searching for ancient objects to be sold on the black market.

United States v. One Triangular Fresco Fragment

Despite the object's obvious Italian origin, the shipment had a customs declaration form which falsified the object's country of origin as Macedonia. The fragment was forfeited to the U.S. government and repatriated to Italy on February 24, 2015.

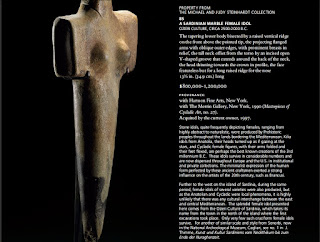

A Sardinian Marble Female Idol of the Ozieri Culture

Before arriving in the collection of Michael and Judy Steinhardt, the object had previously made its way through Harmon Fine Arts and The Merrin Gallery*, both of New York. Once part of the collection of pet food giant Leonard Norman Stern, the object was once displayed, but not photographed, in a "Masterpieces of Cycladic Art from Private Collections, Museums and the Merrin Gallery" event in 1990 where both Steinhardt and Stern were present.

On November 27th the object was pulled from the Christie's auction for further review. Its current status has not be made known publically.

An Anatolian marble female idol of Kiliya type, AKA The Guennol Stargazer

|

Screenshot from “The Exceptional Sale,” April 2017

Image Credit: Christie’s New York |

According to documents, Michael Steinhardt had purchased the Stargazer from Merrin Gallery* in August 1993 for under $2 million. Had the sale not been halted he would have pocketed $12.7 million for the 5,000 year-old Guennol Stargazer, twice the object's pre-sale estimate.

A Marble Head of a Bull (ca 500-460 BCE)

|

Marble Head of a Bull (ca 500-460 BCE),

(image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Earlier this month Manhattan prosecutors took custody of a 2,300-year-old marble bull's head, that was on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art over suspicions that the antiquity had been pillaged.

The marble head of a bull was purportedly purchased by Lynda and William Beierwaltes in 1996 for more than US$1 million. The Beierwaltes in turn sold the statue on to Michael Steinhardt in 2010 who later loaned the antiquity to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After learning that the object might be subject to seizure, Steinhardt asked that the Beierwaltes take possession of the object and compensate him for his purchase.

The Beierwaltes have stated they purchased the object through an unnamed London art dealer. NOTE: The Beierwaltes were clients of Robin Symes and Christos Michaelides.

Six examples of high stakes "risks" overlapping with names of antiquities dealers many of whom those who analyse art crimes will already recognize.

Yearning for Legitimacy or Repeating the Sins of the Father?

Understandably, leading a life on Wall Street makes you look at risk differently than the average person, and hedge fund overlords thrive on tightrope walking high-risk investment tactics in order to bring in lucrative returns. In a world designed to aggressively accumulate wealth, it's not surprising that Michael Steinhardt approached his art acquisitions apparently enjoying the adrenalin-filled rush from the risk-taking he took.

Yet with so many examples of getting it wrong; electing to overlook the provenance of the objects he collected in favor of the buy, working with dealers already known to raised eyebrows or prosecutions for undocumented artifacts, and irregular import documentation, Steinhardt's maneuvers shouldn't be interpreted as simple novice mistakes made by a collector with more money than Midas. Despite that, Steinhardt has profited more than he has been held in account for, which shows, unfortunately, that the odds remain remarkably in his favor, despite the alleged illicit purchases.

Risk vs. Payoff: Lessons from Childhood

But before the legendary Wall Street money manager stepped into the collector's ring, Steinhardt was brought up in working-class Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. He is the son of the late Sol Frank Steinhardt, a reputed gambler and jewelry fence, who was a lieutenant of the prohibition era crime boss Meyer Lansky. Lansky was one of the most notorious of the Jewish crime bosses and a valuable money-maker for Joe Masseria's organization which made much of their income through extortion and is reputed to have been one of the most violent gangs of the era.

A gambler, "Red" Steinhardt, as Sol was also sometimes called, partnered with Lansky in Florida and Havana on gambling rackets that helped finance the National Crime Syndicate, alongside Vincent "Jimmy Blue Eyes" Alo, a New York mobster and a high-ranking Capo in the Genovese crime family.

Before long, Sol Steinhardt's dealings as a farbrekher got him arrested, and in 1958 he was sentenced to 5-10 years on each of two counts for his fencing escapades. Sol served out his sentence at Sing-Sing prison and Dannemora, the maximum security facility along the Canadian border. According to Michael Steinhardt's autobiography, Steinhardt Sr. paid for his undergraduate education at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, – most likely with ill-gotten gains.

Antiquities and Risk

In 2005 Linda Sandler interviewed Michael Steinhardt on antiquities and risk, after his lost his appeal on the gold phiale. During the interview he said:

I guess some collectors aren't candidates for sainthood either.

The moral question is this: Suppose you can legally gain the reward and stick other people with the risk. It is easy enough for me to tell you not to do it. But will it change your action?

By: Lynda Albertson

----------------------------------------------

* The Merrin Gallery was started by Edward Merrin, now run by his son, Samuel Merrin and Moshe Bronstein, appears in the business records of Sicilian antiquities dealer Gianfranco Becchina, who was charged with receiving and trafficking in looted antiquities.

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

No comments

No comments

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

ARCAblog,The Journal of Art Crime

No comments

No comments