Many people are interested in the new exhibition highlighting the 4ft by 4 ft restituted Caligula's ship opus sectile floor fragment which was identified with a Park Avenue art dealer in New York in 2013. And thanks to the efforts of the Manhattan District Attorney's Office and the Carabinieri TPC the object was recovered in 2017 and is back on display now its home museum. Unfortunately, there is also a significant amount of contradictory information flying about in the newspapers about this object's passage through history and the circumstances surrounding its theft. With that in mind, I have tried to outline here only the verified details relating to this unique artefact as we still don't have all the answers.

Two things to note, first, we will update this page as we have confirmatory details from confirmed sources, so check back from time to time. Secondly, much of the plunder described in this post occurred during times when and where it should be emphasized that anyone who had enough money and manpower, was free to legally plunder the relics of Italy in given circumstances. This is why so little material remains from the grand ships of one of Rome's best-known villains.

But let's start with the beginning...

37 CE to 41 CE

|

| Portrait of Caligula |

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the son of general Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder is named Rome's third emperor in succession after Tiberius and ruled for a period of three years and ten months. Throughout history, he would come to be known as Caligula, a childhood nickname bestowed on him by his father's soldiers, derived from the hobnailed sandal boots soldiers and Caligula wore during his father's military campaigns.

Sometime during his reign, Caligula commissioned the construction of several extravagant vessels, two of which archaeology tells us were piloted on the Speculum Dianae, the Mirror Of Diana, one of two lakes formed in the confines of a dormant caldera up in the Alban Hills a short distance from Rome.

|

Lake Nemi by John Robert Cozens, c.1783–8

Image Credit: Tate Britain |

Important to Roman history, the Alban Hills are reputed to be the birthplace of Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome. Given its significance and location, emperors and wealthy Romans built grand villas there, many of which once dotted the body of water we know as Lake Nemi. An important temple to Diana is also situated here.

|

Drawing of one of Caligula's vessels

by Raineri Arcaini, from L'Illustrazione Italiana, Year XXII, No 48, December 1895 Image Credit: Biblioteca Ambrosiana |

Caligula's Lake Nemi vessels were constructed using the Vitruvian method and were roughly the length of a Boeing 747.

They have often been referred to simply as:

Il Prima Nave (the first ship), with a dimension of 67m x 19m

La Seconda Nave (the second ship), with a dimension of 71m x 24m

The exact purpose and eventual use of the two vessels has long been the subject of speculation by scholars, historians, treasure and truth seekers. Each complicated by the paucity of first-hand sources on Caligula's reign.

The bulk of what we know about this infamous ruler comes from Suetonius, who described Caligula's rule unflatteringly and short-lived rule with significant bias, some 80 years after his death. Further writings, by Cassius Dio, were written even later, almost two centuries after Caligula's dramatic death, making it difficult to disentangle dramatised storytelling from historic facts.

But in his writing Seutonius does describe two other ships built for Caligula saying:

"He built two ships with ten banks of oars, after the Liburnian fashion, the poops of which blazed with jewels, and the sails were of various party colours. They were fitted up with ample baths, galleries, and saloons, and supplied with a great variety of vines and other fruit trees. In these he would sail in the day-time along the coast of Campania, feasting amidst dancing and concerts of music."

It is improbably that the two stylistically diverse vessels Caligula placed on Lake Nemi are the same Seutonius described further south in Campania but the writer's descriptions of their use and the remains recovered from each of these vessels documents ships of similar grandeur. During the early days of the discovery of the ships beneath Lake Nemi, it was thought is that one of the two Lazio lake vessels was used as a floating temple either to the Roman goddess Diana, given her temple beside the lake. Another theory surmised that one was used to honour Isis during the festival of Isidis Navigium, a ritual dedicated to her role as protector of sailors.

Given the grandeur of their size, and the artefacts that have been documented as being salvaged from them, it is believed that the second ship served as a grand and floating palace fit for an emperor known for his exaggerated extravagance.

22 January 41 CE

But it didn't take long for the capriciously despotic ruler to overstay his welcome with the citizens of Rome. At 28 years of age, Caligula was assassinated walking back from the Palatine Games. Ironically, he was murdered for his tyranny by Cassius Chaerea, a tribune of the Praetorian guard, the elite unit of the Imperial Roman army responsible for his personal security and to whose very support this emperor owed his accession. Inflicting the first of some thirty stab wounds, his killers strove to end the principate, and its violence is reminiscent of Julius Ceasar's own demise.

|

Gaius (Caligula) Sestertius

Rome mint. Struck 37-38 CE. |

43 CETwo years after his death, and given the recent memory of the young emperor's cruelty and debauchery (as well as his habit of tossing coins struck in his image to the populace he hoped to influence), the senate ordered all bronze aes coins bearing Caligula’s image be melted down, enacting the most famous example of demonetization in the Roman world. Other coinages with his image were scratched, clipped, or simply defaced, making his remaining coinage some of the most defaced within the numismatic corpus. This form of posthumous punishment was passed by the Roman Senate to those they believed brought extreme discredit to the Roman State.

And while his successor Claudius prevented the Senate from officially expunging his nephew Caligula, he himself moved to strip the despot of all imperial titles in the Fasti and demanded that images in his likeness be destroyed, or at minimum, removed from public sight. Their intent, in one way or another, was to erase Caligula from the memory of the people, and in doing so, preserve the honour and restore the dignity to the empire, a task somewhat easier in ancient times, when written documentation was much sparser.

Likely after 41 CE

No written records document precisely when, or under what circumstances, Caligula's two lake vessels sank following his assassination. Some say the vessels may have been deliberately sunk by order of Caligula’s successor Claudius, a more benign and prudent ruler who came to power unexpectedly after the assassination of his nephew. Others speculate that the vessels simply floated on the lake abandoned until they eventually sank of their own accord after their outer lead sheathing become waterlogged.

Whichever is the case, Prima Nave and Seconda Nave lay silently preserved, not far from one another, on the muddy bottom of the Speculum Dianae for over nineteen hundred years. The first vessel at a depth stretching from five to fifteen metres, given the inverted conical shape of the dormant volcano. The second, at a right angle to the first, in slightly deeper water, at twenty metres beneath the lake's surface.

|

Portrait of Cardinal Prospero Colonna

by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, ca. 1750

Image Credit: The Walters Museum |

1446

After fishermen brought him pieces of timber they had fished from Lake Nemi, Cardinal Prospero Colonna, the nephew of Pope Martin V, and the Lord of the castles of Genzano and Nemi as well as the land and the lake, became intrigued. He commissioned Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti to organize an attempt a recovery the first of the vessels at Nemi. At the time, and without confirmatory historic details, the ship was believed to have been placed on the lake during the reign of Caligula's predecessor, Tiberius Caesar Augustus, the second Roman emperor.

In setting about his recovery operations Alberti, one of the most experienced hydraulic engineers of his time, created a floating retrieval platform above the Prima Nave, constructed his extraction platform from empty barrels for pontoons and windlasses.

Using mounting winches with hawsers and grappling hooks, the architect then attempted to hoist Primo Nave ashore. But with material installed above the lake's surface was wholly inadequate for the job and Alberti's attempts failed. The embedded ship remained firmly on the lake's bottom firmly in the grip of Nemi's thick muddy silt. Disastrously, this first attempt at salvage ripped away a section of the prow as well as planks from the ship's bow.

In concluding their campaign Alberti's diving crew salvaged only a few remains, mostly marble fragments, bronze nails, and plates of lead tacked on the ships exterior to reinforce the hull. But a few of the pieces recovered turned out to be very important. Those were portions of three lead water pipes (fistulae), their use not yet understood. Despite the questions about their use, each of these simple pipes did more to date the vessel than any recovered masonry brick stamp or architectural element as stamped on each, were the words property of Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus:

G. CAESARIS AVG GERMANIC

|

Pipe with Caligula's Inscription from the Primo Nave at Nemi

Image Credit: Museo delle Navi di Nemi |

Despite failing to raise the vessel, the undertaking caused such a spectacle that even the grand ladies of the Pontifical Court came out to inspect the progress of Alberti's men, sometimes even carrying off small mementoes from the scraps the workmen recovered, which were then taken back to Rome, most eventually lost to time.

July 1535

Nearly a century later, and more than 150 years before the invention of the modern diving bell, a second attempt to raise one of Caligula's vessels in Lake Nemi, was attempted. This time utilizing the earliest recorded employment of a breathing apparatus in underwater archaeology.

For the second attempt inventor, Guglielmo de Lorena created an improvised contrivance using a weighted wooden box that reached the waist of military engineer Francesco de' Marchi, allowing him to breath for short periods underwater. Once submerged de' Marchi attempted to survey the length of the emperor's vessels, though his observations were met with limited success, impeded by the distortion of the glass window on the inventor's diving box.

Ultimately, like Alberti's efforts before him, de' Marchi attempts to hoist Prima Nave up and out of Lake Nemi's mud with ropes and winches failed. And his salvage attempts inflicted further damage to the ancient vessel, nibbling away like the fishes, at more sections of the ship's skeleton. In addition to that, de' Marchi's cumulative diving sessions impacted his body, as his experimental time underwater caused his nose, mouth, and ears to bleed from the barotrauma of his explorations.

Unable to raise the ship, their only rewards for their exploits, aside from de' Marchi's descriptive, if embellished, tale of his historic adventure, was the retrieval of a grouping of artefacts manually salvaged using a windlass working from a raft floating above. Their haul is described as having been "two mule-loads" of material, brought to the surface after multiple dives of a cumulative duration of many hours.

The motivating factor for this exploration and most subsequent attempts at salvage on Caligula's ships, before the final success, was not archaeological in nature. The higher priority for the people involved was finding treasure for profit, rather than exploration.

de' Marchi's salvage operation is known to have brought up portions of the ship's two feet square pavement tiles, segments of red marble, more lead piping, nails and lead sheathing. As with the first attempt, gawkers too, wanted their own bits of the ancient past and history records that scavengers at one point broke into de' Marchi's home in order to steal bits and bobs recovered during the second exploration.

Between 1535 and 1827

Using grappling hooks and other devices, local "entrepreneurs" continued to extract remnants from the ships, selling the pieces fished from the lake willy nilly, particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the tradition of the ‘Grand Tour’ as part of one's aristocratic education become popular among wealthy European gentlemen.

September 1827

Almost three centuries after the last attempted salvage, a third attempt to raise Prima Nave was conducted by Annesio Fusconi, an engineer, who used a large, eight-person Edmond Halley style diving-bell. This device replenished the air for the submerged divers with air carried in casks.

To increase the spectacle of the salvage exploration, Fusconi built a viewing stage, complete with a bridge where illustrious invited guests of Roman and foreign nobility, as well as the diplomatic corps, could be entertained by the workmens' performance.

Like with the previous two attempts, the third team used a floating platform, this time content with possibly dismantling the Prima Nave, rather than hoisting the ship up whole. Their plan called for pulling smaller sections of the hull to the surface. Thankfully, however, Fusconi's ropes failed and bad weather intervened. The ships, more or less, after years of sporadic scavenging, remained more or less intact, below the lake's surface.

Fusconi catalogued the material he salvaged in his memoirs, giving a precise list of what he recovered, some of which included:

"two rounds of pavement, one of oriental porphyry and the other of serpentine, pieces of marble of various qualities, enamels, mosaics, fragments of metal columns, bricks, nails, terracotta pipes and finally wooden beams and boards".

The major finds Fusconi extracted were purchased by Cardinal Camerlengo for the Vatican Museums; though some rare pieces were also kept by Fusconi himself, and were said to have been placed in a warehouse of one of the palaces of the Prince Alessandro Torlonia who it can be assumed, purchased at least a portion of what remained from this recovery campaign.

Some of these finds were repurposed to suit the whims of Prince Torlonia and were once proudly displayed in Palazzo Bolognetti-Torlonia at Piazza Venezia in Rome. There, he had several furnishings built with wood recovered during the 1827 salvage, including a gothic style cabinet. His workmen also lay down flooring using some of the terracotta recovered from Nemorense ships.

Yet despite the advances in this salvage operation, the only portable remnants recovered by the state from this third attempt is a single beam fragment with nails, absent its documented golden head.

Many other wooden beams and boards were lost to us, inconsequential in size, they are believed to have been widdled into souvenir smoking pipes, or used to make snuffboxes, secretaries, and travel boxes. What wood that was recovered and not repurposed was eventually stolen when work was suspended for the season. To add insult to injury, thieves even made off with the Halley diving apparatus, perhaps hoping to use the device themselves in search of their own treasure.

3 October 1895

On behalf of the Orsini family, who now controlled the territory in and around the lake, and with the authorization of unified Italy's Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione, a fourth and slightly more systematic study of the wrecks was undertaken, directed by the antiquarian Eliseo Borghi. With a bit of ingenuity, involving Lieutenant Colonel Vittorio Malfatti and an expert diver, whose name is now lost to us, the crew systematically attached long cords along the contours of the two galleys topped with small cork buoys. This allowed a surface level outline of each of the vessels showing exactly where they came to rest below the lake's surface. The divers' corks also provided a more accurate means of measuring the width and length of each of the extravagant vessels.

|

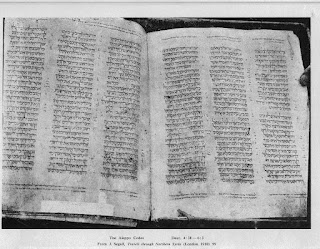

Left: Recovered Floor Fragment from Caligula Vessel

Right: Alternating Complimentary Floor Fragment showing same artisan workmanship from Caligula Vessel |

While undertaking their explorations, the team also documented that the decks of one of the ships had been paved with opus sectile in Egyptian red porphyry, green serpentine porphyry from Sparta, and Rosso Antico from Greece, defining when the stolen opus sectile fragment was originally found. They also determined that the bulwarks had been cast in solid bronze and at one point were probably gilded. It is during this operation that for at least the first time, some of the vessels' artefacts made it into museums, including an important bronze ferrule depicting the head of a lion holding a mooring ring in its jaws believed to have once adorned one of the steering oars.

Working the salvage, divers brought up the ship's famous bronze proteomes as well as the portions of the ship's opus sectile flooring, including the fragment that made its way illegally to New York. Other artefacts recovered include more lead pipes, ball bearings, floorboards, hinges, bronze threads, gilded bronze roof tiles, gilt copper tiles, bricks of various shapes and sizes, and fragments of mosaics with glass paste embellishments.

|

Rudder in the shape of a forearm from Caligula’s Seconda Nave at Nemi

Image Credit: Palazzo Massimo alle Terme |

18 November 1895

On November 18th the second ship in Lake Nemi is identified. Salvagers recovered a bronze panel depicting a forearm and hand from La Secondo Nave, believed to have been used as a support for one of the vessel's rudders as well as a striking head of Elios from the bow of the ship. Another evocative find was the head of Medusa, aptly described at the time by Carlo Montani who said:

"It emerged from the blue waters of the lake, into the arms of the diver who had torn it from the sunken hull. The beautiful bronze head, dripping with water, seemed to shed tears of pain for its peace of centuries unexpectedly disturbed".

|

Head of Medusa, recovered in 1895

Image Credit: Palazzo Massimo alle Terme |

Some of the more precious objects recovered were purchased by the Italian government for the Museo Nazionale Romano. Others, some of great importance, were quickly disbursed, bought by private collectors or lost over time. This includes a statue of Diana or Drusilla, and eight other statuettes which disappeared almost immediately after being brought to the surface.

One of these statues is now believed to now be in the British Museum. Another, a statuette of Eros, eventually turned up in the Hermitage Museum, after a circuitous journey via England. More common everyday items, like a bronze asimpulum (ladle), can be found in Paris at Musée du Louvre and a large monumental helmet was eventually sold onward to a museum in Berlin.

As rightly said by the Comune of Nemi, the only consolation for the loss of these important artefacts abroad, now in the collections of foreign museums is that these important pieces can be surrounded by admiring visitors, affording them a level of respect and adoration, that they didn't find in Italy during the salvage of the late 1800s. With their presence abroad, each serves as an ancient ambassador which tells the story of Italy's great past.

But while recovering these works of art, salvagers removed and quickly discarded some 400 meters of beams from the two ships, material which could have served in their eventual reconstruction. Instead, the beams were left to disintegrate under the baking sun. Some were eventually repurposed for other ordinary things, and what was left was simply broken up for firewood.

8 December 1908

A Washington Post article documents that Eliseo Borghi has some of the salvage from Caligula's ships in his private museum, one of which is the later stolen opus sectile floor fragment, a photo of which is included in the US newspaper.

The article states that the Italian government offered Borghi 23,000 lire for the pieces (roughly $4,600 at the time). At the same time the Metropolitan Museum offered him 30,000 lire, but the latter offer was declined by the Italian government, meaning the the remaining objects in Borghi's possession were not approved for export.

1926

Talks begin for another attempt at the recovery of the vessels at Lake Nemi. An engineering commission is formed and entrusted to Corrado Ricci. After careful analysis, Vittorio Malfatti a participant of the 1895 salvage, proposes a fifth and final attempt, centering on a completely new technique, partially emptying the lake in order to lay bare the two submerged vessels allowing the hulls to be dug out of the mud.

9 April 1927

Benito Mussolini gives a speech to the Reale Società Romana di Storia Patria and announces his decision to move forward with the recovery of the ceremonial ships of Caligula, approving the lowering of the water table of the lake.

1928 - 1932

Work begins at Lake Nemi under the orders of Benito Mussolini in what would become at the time, perhaps the greatest underwater archaeological recovery ever accomplished.

|

| Revised drainage plan engineers used opening an ancient emissary |

20 October 1928

Workmen set about emptying Lake Nemi. The original proposal had been to dig a channel that would redirect the waters of Lake Nemi into nearby Lake Albano, which lay at a lower level. As the project got underway, it was decided instead to bore a tunnel, some 1,653 meters in length through hard volcanic rock and then grafting the newly created tunnel to a preexisting 6 BCE emissary older than the ships themselves. If their engineering plan was valid, and provided they could safely clear all the debris from landslides crowding into the ancient flood control channel, the engineers could divert the lake's water all the way through the Arcia valley and into the Mediterranean sea 30 kilometres away.

31 December 1928

By the end of December, five million cubic meters of water had been extracted from Lake Nemi, half of what was needed for the emergence of the stern of Prima Nave.

|

| Italians lined up to see Primo Nave, now on dry land, 1929 |

28 March 1929

By the end of March, Primo Nave lay on dry land and efforts of the Nemorense commission turned to the protection of the exposed vessel and its contents. Given the size of the ship and its fast deterioration after being exposed to air on the surface, temporary shelters needed to be built. Likewise, plans immediately got underway to build a bespoke museum, designed by the architect Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo, which would be large enough to house both ships once their extraction had been completed.

End of January 1930

As the pumping continued, the Seconda Nave broke the surface. 70 meters long and over 20 wide, it was adorned richly with marble floors as well as objects related to the cult of Isis.

|

Artefacts recovered in a photo dating to the 1930s

showing the stolen opus sectile floor fragment at centre |

The 1930sThe decade documented, exact year unknown, to the last known photo showing the opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship in Italy.

1935

Primo Nave is towed on a specially constructed roller system inside the partially completed Museo della Navi di Nemi.

20 January 1936

With the facade of the museum still unfinished, the second ship is installed inside the future Museo della Navi di Nemi.

1 September 1939

World War II begins.

|

| Photo of the Inauguration of the Museo della Navi di Nemi |

21 April 1940

The opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship and many of the other historic artefacts recovered from the two vessels are moved into the newly completed Museo della Navi di Nemi shortly before its 21 April 1940 inauguration by Benito Mussolini.

10 June 1940

Italy entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers.

Date Unknown

The opus sectile fragment from Caligula's ship and other artefacts are removed from the museum. It is unclear if the illegally exported fragment was first removed to a storage depot for safekeeping during the war in Rome when other movable objects at the museum were transferred for safekeeping, or if the flooring fragment was left behind and disappeared directly from the collection.

|

| The refugees of Genzano and Nemi housed in the premises of the museum before they were expelled in April 1944. |

Sometime between February and 3 April 1944As life for Italy's citizens worsened during the war, several dozen families, displaced war evacuees from Genzano and Nemi bivouacked inside the Museo della Navi di Nemi. As depicted in the photograph above, taken inside the museum during their stay, beds, tables and chairs, as well as pots, pans and containers for cooking are clearly visible alongside the flank of one of the ships creating a precarious situation.

After two months, and given the increased risk of fire to the museum's collection presented by the activities of the museum's temporary residents, superintendent Aurigemma, who had responsibility for the ships, had the family's expelled on April 3rd causing great consternation to those ejected. The museum's keepers, under the approved sanctions of the Germans, were allowed to remain inside, while some of the now disgruntled homeless are forced to take shelter in the caves surrounding the lake or transfer to Umbria.

27 -28 May 1944

According to informal reports the German military set up a defensive point in Nemi on 28 May 1944. Despite the German's apparent respect for the museum's importance, the 163rd German Motorized Antiaircraft Group places a battery of four guns in a position one hundred meters from the naval museum. With guns pointed at their chests, the keepers of the museum report that they were evicted, taking up refuge in the caves found on the slope of the volcanic basin of Nemi where they could observe the museum from a distance.

31 May 1944, morning and afternoon

With the Germans having begun their retreat, after the Allied landings at Salerno in 1943 and Anzio in January 1944, the US and British air forces conducted a bombing raid around the area of Lake Nemi to push the German troops northward. All reports indicate that despite the bombardment, no bombs fell on the Museo della Navi di Nemi that day, and all bombing ceased before nightfall.

Possibly 31 May 1944, 22:00 (some believe this date is not accurate)

The date widely publicised as the date of the museum fire, stated to have occurred at around 10 pm in the evening at the Museo della Navi di Nemi.

|

| After the fire at the Museo della Navi di Nemi |

May 31 to June 10, 1944

The more realistic date range established for when the fire likely occurred at the Museo della Navi di Nemi. In either case, the destruction caused by the raging fire inside the cement walls of the museum is almost total. The extraordinary ships of Caligula, raised from the basin of Lake Nemi, are reduced to cinders.

21 July 1944

To ascertain the circumstances in which the disaster occurred at the Museo della Navi di Nemi, a commission of inquiry is quickly set up just fifty days after the fire.

The composition of that commission was:

Captain Giorgio Brown, in charge of the fire brigade in Rome

Salvatore Fuscaldi, of the artillery technical service in Rome

Enrico Pietro Galeazzi, general manager of the Technical Services of the Vatican City State

Gustavo Giovannoni, Professor of Architecture

Vito Magnotti, lieutenant colonel, commander of the brigade in Rome

Bartolomeo Nogara, general director of the Pontifical Museums

Roberto Paribeni, former director general of Antiquities and Fine Arts

Erik Sioquist, director of the Swedish School in Rome

No police investigators are assigned and the conclusion of the commission is considered, by some, to have been too rapid for a thorough investigation of the events surrounding the fire.

Despite this, the commission concludes:

"that, with all likelihood, the fire that destroyed the two ships was caused by an act of will on the part of the German soldiers who were in the Museum on the evening of May 31, 1944."

January 1946

After the war, the cause of the fire may have been further whitewashed, perhaps to hide inconvenient truths. In January 1946 L'incendio delle navi a Nemi (the Fire of the Ships of Nemi) is published in January-February 1946 as an excerpt from Rivista di Cultura Marinara. This report echoed the commission's initial findings saying that the German military had arrived in Nemi on 28 May 1944 and the Allied bombing was aimed at addressing a Nazi anti-aircraft battery made up of four guns but did not target the museum.

Testimony from the keepers the museum used in this report implied that German soldiers from the 163rd German Motorized Antiaircraft Group had wandered into the museum on the night of the 31st and chased away the museum's personnel. Then, with lighted torches in hand, it is alleged that the soldiers deliberately set fire to the museum's contents, commenting that the Germans, aware of their imminent retreat, planned to leave a "very serious loss to Italy" as they departed.

Some scholars have hypothesized that the fire may have started after the departure of the Germans as an intentional act of partisan arson, possibly carried out by the antifascists in the region who had reason to despise Mussolini and his projects, including the raising of Caligula's ships as a direct and influential instrument of his fascist propaganda. But despite this theory, no concrete evidence has been produced to flesh out this assumption, aside from the fact that there were known partisan groups in the Alban Hills.

What we do know concretely is that the Museo della Navi di Nemi and the ships inside it were of no military importance for either the Axis or the Allied powers. Likewise, we have documented proof of the Germans sparing other sites of cultural importance during the war.

It would also seem unlikely that a German commander would have given an order to torch this sole museum to destroy its contents given it also had access to others within Italy and didn't do so. It is even more unlikely that a subordinate soldier would have run the risk of incurring the anger of his superiors by going rogue and torching the museum without orders from his higher-ups.

The written record of what was carried out to rule out a short circuit in the electrical system in a museum built at an extremely fast pace, or to rule out other causes due to war operations is severely lacking.

What we can conclude is that regardless of who, or what, was responsible for the fire itself, that fact that the German command placed an artillery position near the museum and then elected to forcibly eject the keepers of the museum, preventing them from identifying, and extinguishing the fire before it blazed out of control, created a perfect storm which led to the disastrous loss of Caligula's ships.

1955

The incorrect year that many newspapers say dates the last known photo of the stolen opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship.

The late 1960s

Date range given in various newspaper statements as the period when the opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship was purchased. Art and antique dealer Helen Fioratti has reported that she and her husband Nereo Fioratti, a foreign press correspondent and journalist with Italy’s newspaper Il Tempo, purchased the artefact from an aristocratic Roman family, sometimes reported as the Barberini family in some news accounts. In other differing articles Helen Fioratti claimed that the couple innocently purchased the artefact from "an Italian art historian" or an "Italian police official..." known for his work recovering art stolen by the Nazis.

Assuming Fioratti is referring to Rodolfo Siviero, I have found no evidence to support her statement.

Date Unknown

The opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship is taken out of Italy and imported into the U.S. How the Fiorattis arranged for its transport to their New York Park Avenue apartment is unknown.

1960

The opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship resurfaced when it was purchased by the antique dealer Helen Fioratti and her husband Nereo Fioratti, a foreign press correspondent and journalist with Italy’s newspaper Il Tempo. They said they bought the piece in good faith from an aristocratic family and used it as a coffee table for years.

March 1991

The Park Avenue home of Helen Fioratti is featured in Architectural Digest, but despite being photographed, the opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship is not immediately identified by law enforcement authorities.

23 October 2013

Dario Del Bufalo, an Italian expert on ancient marbles, gave a talk in New York during a book signing for his new book “Porphyry,” on the rare reddish-purple stone preferred by the Roman emperors. During the event, which took place at Bvlgari's 5th Avenue and 57th Street location, Del Bufalo reports that a gentleman on hand for the signing, leafed through his book and identified the opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship as one which could be found in the apartment of Helen Fioratti on Park Avenue.

20 October 2017

The District Attorney’s Office in Manhattan announces that following a formal request for judicial assistance from the Italian Carabinieri, the opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship has been seized pursuant to a judicially authorized warrant. After its seizure, the historic artefact was forfeited willingly by Helen Fioratti, once presented with the evidence that the artefact was stolen from Italy.

2018

The opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship undergoes conservation to remove the stains of everyday use as a coffee table.

May 2019

After its restoration, the opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship at Lake Nemi is formally displayed the Quirinale in Rome.

March 2021

The opus sectile floor fragment from Caligula's ship at Lake Nemi is back at the Museo della Navi di Nemi alongside wat material culture remains of the once-grand ships of Caligula.

By: Lynda Albertson

References consulted in this article

----------

Alberti, Leon Battista. I Dieci Libri de L’Architettura: Book V. Venice: Vicenzo Vagaris, 1546.

Alessandra. ‘Il Museo Delle Navi Di Nemi: Cattedrale Dell’assenza’. Nemora (blog), 30 October 2016. https://www.nemora.it/museo-delle-navi-romane-nemi/.

Manhattan District Attorney’s Office. ‘Ancient Roman Mosaic Among Collection of Artifacts Being Repatriated to Italian Republic by Manhattan District Attorney’s Office’, 20 October 2017. https://www.manhattanda.org/ancient-roman-mosaic-among-collection-of-artifacts-being-repatriated-to-italian-republic-by-manhattan-district-attorneys-office/.

Barrett, A. ‘The Invalidation of Currency in the Roman Empire: The Claudian Demonetization of Caligula’s Aes’. In Roman Coins and 201 Public Life under the Empire. E. Togo Salmon Papers II, edited by G. Paul and M. Ierard. University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Biondo, Flavio. Roma ristaurata, et Italia illustrata di Biondo da Forli. Tradotte in buona lingua uolgare per Lucio Fauno. appresso Domenico Giglio, 1558.

Bruno Brizzi. ‘Chi Incendio’ Le Navi Di Nemi?’ La Strenna Dei Romanisti LXXII (2011).

‘C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Caligula, Chapter 37’. Accessed 13 March 2021. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:abo:phi,1348,014:37.

‘Caligula-Ship Mosaic Returned to Italy’. ANSA, 20 October 2017. https://www.ansa.it/english/news/lifestyle/arts/2017/10/20/caligula-ship-mosaic-returned-to-italy-2_c717679f-3645-41ba-8d31-67ef7725e6aa.html.

Cappellari, Pietro. ‘Lo Scandolo Della Navi Di Nemi’, 2020.

De’ Marchi, Francesco. Della Architettura Militare. Gaspare dall’Oglio, 1599.

Di Benedetti, G. Le Tre Navi Antiche Del Lago Di Nemi, 2016.

Eliav, Joseph. ‘Guglielmo’s Secret: The Enigma of the First Diving Bell Used in Underwater Archaeology’. The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology 85, no. 1 (2015).

‘Emperor’s Mosaic Displayed in Italy after Stint as NYC Table Park Avenue’. The Independent, 12 March 2021. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/emperors-mosaic-displayed-in-italy-after-stint-as-nyc-table-italy-caligula-nyc-rome-park-avenue-b1816029.html.

‘Il rogo delle Navi di Caligola: non fu appiccato dai nazisti ma da “partigiani”’. Il Primato Nazionale (blog), 27 July 2020. https://www.ilprimatonazionale.it/cultura/rogo-navi-caligola-nemi-non-furono-nazisti-ma-partigiani-163828/.

Knowles, James. The Nineteenth Century and After. Leonard Scott Publishing Company, 1909.

Comune di Nemi. ‘Le Navi Di Nemi Di Marina e Massimo Medici’. Accessed 14 March 2021. http://www.comunedinemi.it/le_navi.html.

Leafloor, Liz. ‘Oath of Silence Protects Amazing 500-Year-Old Diving Bell Used to Visit Sunken Roman Vessels’. Caput Mortuum (blog), 15 July 2015. https://lizleafloor.com/2015/07/15/oath-of-silence-protects-amazing-500-year-old-diving-bell-used-to-visit-sunken-roman-vessels/.

Lowell, John Amery. The Antiquary. Harvard College, 1905.

maraina81. ‘31 maggio 1944: bruciano per sempre le navi di Nemi’. Generazione di archeologi (blog), 16 July 2018. https://generazionediarcheologi.com/2018/07/16/31-maggio-1944-bruciano-per-sempre-le-navi-di-nemi/.

McKinley, James C. ‘A Remnant From Caligula’s Ship, Once a Coffee Table, Heads Home’. The New York Times, 20 October 2017, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/19/arts/design/a-remnant-from-caligulas-ship-once-a-coffee-table-heads-home.html.

Nadeau, Barbie Latza. ‘The Odd Stains on Caligula’s Stolen Orgy Ship Mosaic Finally Cleaned’. The Daily Beast, 11 March 2021. https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-odd-stains-on-caligulas-stolen-orgy-ship-mosaic-finally-cleaned?fbclid=IwAR3vZkXAn6Im40MudZ2HSb5iI5R-MK_YTFQU2d55UB-Nhg3hbWWfFgek5L0.

‘Newly Discovered: A Mosaic from Caligula’s Pleasure Barge Being Used as a Coffee Table in N.Y.’ Washington Post, 20 October 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/10/20/newly-discovered-a-mosaic-from-caligulas-pleasure-barge-being-used-as-a-coffee-table-in-new-york/.

Pollini, John. ‘Recutting Roman Portraits: Problems in Interpretation and the New Technology in Finding Possible Solutions’. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 55 (2010). https://www.academia.edu/44584464/John_Pollini_Recutting_Roman_Portraits_Problems_in_Interpretation_and_the_New_Technologiy_in_Finding_Possible_Solutions_in_MAAR_55_2010_24_44.

‘Roman Wrecks of Lake Nemi – National Maritime Museum of Ireland’. Accessed 13 March 2021. https://www.mariner.ie/lake-nemi/.

‘Roman Relics Vanish; Borghi Collection May Be on Its Way to This Country. Government to Investigate Valuable Art Treasures Recovered from Bottom of Lake Nemi Believed to Have Been Secretly Sold to New York Metropolitan Museum -- Italy’s Scheme to Recover Other Treasures.’ The Washington Post, 8 December 1907. https://www.flickr.com/photos/imperial_fora_of_rome/2538328266/in/photostream/.

Speziale, G. C. ‘The Roman Galleys in the Lake Nemi’. Mariner’s Mirror 15, no. 4 (1929).

Squires, Nick. ‘Stolen Mosaic That Once Adorned Emperor Caligula’s Lavish Pleasure Barge Returned to Italy after Being Used as a Coffee Table’. The Telegraph, 20 October 2017. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/10/20/stolen-mosaic-adorned-emperor-caligulas-lavish-pleasure-barge/.

Stapley-Brown, Victoria, and Helen Stoilas. ‘Mosaic Floor from Caligula’s Ship Returned to Italy’. The Art Newspaper, 23 October 2017.

Suetonius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. G. Bell and sons, 1890.

Ucelli, Guido. Le Navi Di Nemi. Instituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1950.

Youtube - Videomaker. Ritrovato Il Mosaico Perduto Di Caligola, Torna al Museo Di Nemi, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vNKlbiVzHA.

antiquities looting,antiquities market,Caligula,Italy,Roman,Smuggling; Collecting; Collections; Rome; Export Law

antiquities looting,antiquities market,Caligula,Italy,Roman,Smuggling; Collecting; Collections; Rome; Export Law

No comments

No comments