The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) has abandoned its legal fight to prevent the seizure of a prized bronze statue depicting the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Valued at $20 million, the artefact was looted from Turkey in the 1960s.

The decision comes, almost a year and a half, after New York investigators issued its seizure order, on 31 August 2023, on the basis that the statue constitutes evidence of, and tends to demonstrate the commission of the crimes of, Criminal Possession of Stolen Property in the First Degree, Penal Law § 165.54, and a Conspiracy to commit the same crime under Penal Law § 105.10(1).

The museum, which has featured the bronze in its collection since 1986, had challenged the order in court, arguing that there was insufficient evidence to prove the statue had been illegally exported. In their lawsuit, the museum claimed that the headless sculpture, controversially named The Emperor as Philosopher, probably Marcus Aurelius, then renamed Draped Male Figure, had been lawfully acquired by the museum and that New York District Attorney Alvin L. Bragg’s office in Manhattan has no legal authority to seize it.

In its prior federal filing, Cleveland Museum of Art v. District Attorney of New York County, New York (1:23-cv-02048), Cleveland had opposed the return of this statue contending that its former curator Arielle P. Kozloff (Herrmann) believed that the Philosopher did not come from Bubon, and that any previously stated connection between Bubon and the Philosopher was mere conjecture, statements which completely contradict the museum's earlier findings.

|

Vol. 74, No. 3, Mar., 1987

The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art |

After its purchase, the Museum was so proud of its acquisition of unknown origin that it dedicated its entire its March 1987 edition of The Bulletin of The Cleveland Museum of Art to the statue and highlighted the bronze in a Year in Review exhibition. Curator Kozloff wrote in the Introduction to that 62-page Bulletin that “[t]his entire issue of the Bulletin is devoted to the study of Cleveland’s newly acquired bronze.” At page 133, she quoted English archaeologist and writer George Bean’s observations when he visited Bubon and described the difference at the site between his first visit in 1952 and his second visit in 1966:

“[T]he scene completely changed. The entire slope of the hill had recently been dug from top to bottom by the villagers in search of loot; their pits left hardly a yard of space between them. Of the ruins, such as they were, nothing now remains; but in the course of digging in the theater a large stone covered with writing was said to be found.”

Kozloff also published photographs of her trip to Bubon, including one which she captioned “Figure 3. The photograph depicts the extent of the looting: giant holes scar the landscape and fragments of stone walls can be seen jutting out of the pits.” Kozloff also included another photograph to illustrate the find spot of the looted statues:

On a longitudinal axis leading to the northeast (nearly parallel to the axis of the “agora”) from the theater are two structures, now pits, about 2 meters deep and mostly filled in with debris (Figure 3). The smaller of the two was pointed out by an Ibecik native as “the museum” where eight large statues were found. Our guide’s arm gestures indicated that the sculptures were found tumbled together, face down in the earth. Our guide remembered only human figures being unearthed and reported a quantity significantly less than what is claimed for the site.

Effectively, Kozloff admitted, in CMA’s own official publication, that the Sebasteion had been heavily ravaged “by the villagers in search of loot” between 1952 and 1966—all while trumpeting CMA’s newly acquired statue had originated from this very site.

At the time of its celebratory exhibit, the Cleveland Museum of Art issued a statement that it would be exhibited their new bronze with "one other sculpture supposedly found with it, a bronze bust of a lady, now in the Worcester (Massachusetts) Art Museum." That identified object as already been returned by the New York District Attorney's Office, making it all the more outrageous, that on one hand the museum admitted to the statue's origins from Bubon, while in 2023 foot-dragging against the the realities they themselves had fully acknowledged years earlier.

Today, the CMA formally filed a Notice of Dismissal Under FRCP 41(a)(1), electing to drop its opposition of the statue's seizure. This now paves the way for the artefact's eventual return to its country of origin. In opting to dismiss, the museum issued a statement published in the New York Times that the decision was predicated on the basis of scientific study, which only now allowed the museum to be “able to determine with confidence that the statue was once present at the site.”

Over the last several years, the Manhattan District Attorney's Office Antiquities Trafficking Unit, headed by Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos has been actively involved in the repatriation of stolen artefacts, including many bronzes identified as having been looted from the ancient city of Bubon in Türkiye. In recent years, prosecutors and analysts with the ATU have worked closely with academics studying the bronzes and the Turkish authorities in order to seize, where possible and in accordance with the law, antiquities looted from this ancient site that were laundered through the black market.

By May 1967, law enforcement authorities from the Republic of Türkiye had uncovered their first lead which would help identify where the looted statues came from. A large, ancient bronze statue was found hidden in a looters house in the village of Ibecik, located in the mountainous region of the Gölhisar district, in the southern province of Burdur, less than 100 kilometers from the southwest Turkish coast.

This initial investigation, coupled with studies by Turkish archaeologist Jale İnan on behalf of the museum in Burdur, as well as notes gathered and seized from a local treasure hunter during investigations, helped to establish the find spot for the CMA bronze and other statues which once stood on the summit and slopes of Dikmen Tepe within the eastern Roman Empire city of Bubon.

According to the ancient Greek geographer Strabo, the city of Bubon formed a tetrapolis with its neighbouring cities of Cibyra, Oenoanda and Balboura. Culturally diverse, at its pinnacle its inhabitants are said to have spoken as many as four languages: Greek, Pisidian, Solymian and Lycian.

Travellers to Bubon as late as the mid-19th century described finding a walled acropolis, a small theatre of local stone, and the remains of tombs, temples, and other large structures in what remained of the ancient city. Few of these survive today. Decimated by a large-scale looting operation conducted during the mid-20th century, the unprotected ancient city's movable cultural heritage fell victim to poverty and art market greed, with much of what had survived throughout history, being dug up and hauled away for profit.

.png) |

| The Sebasteion at Boubon |

In 1967, the archaeological museum of Burdur undertook the first legal excavation at what remained of Bubon. During these emergency excavations, where some of the explored sites were reburied after exploration to afford more protection, site archaeologists documented a Sebasteion near the centre of the terrace close to the Agora. This complex is believed to have been devoted to the worship of the imperial cult, honouring members of the Imperial family. It is thought to have been in use for a period of over two centuries from the 1st to the middle of the 3rd century CE.

Inside this Sebasteion, archaeologists discovered two inscribed podiums along the north and the east walls of the room, as well as four free-standing bases along the west wall. Here, statues of emperors and members of the Imperial household were once on display.

The majority of the dedications found at the Sebasteion date the cult sanctuary from the half century beginning with the joint reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (161-168 CE) to the ending of the sole reign of Caracalla (211-217 CE). Unsurprisingly, by the time archaeologists set about documenting the site, only one single headless statue remained.

All the others had been clandestinely excavated and illicitly exported out of the country.

As part of this documentation, Jale İnan assigned names to seven of the missing bronze statues, based on seven of the 14 dedicatory inscriptions found in situ at the Sebasteion. According to the researcher's reconstruction, patrons or visitors entering this room in the middle of the 3rd century CE, would have seen bronze statues of Nerva, Poppaea Sabina, Lucius Verus, Commodus, Septimius Severus, and lastly, Marcus Aurelius who would have stood on a podium or plinth facing the entrance.

One of three inscriptions discovered during J. İnan's excavation, on stones forming the top course of the north pedestal (blocks E 10 and 11), documented in his 1990 excavation notes, reads:

[Μ.Αυρήλιο]ν Άντωνεϊνον

Over the subsequent years, it was determined that as many as nine, possibly ten, life-sized bronze statues originating from Bubon had been excavated and sold onward, first by the site's looters and middlemen, then onward to a dealer in Izmir, a city on Turkey’s Aegean coast. From there, it has been established that some were smuggled out of the country and into Switzerland, passing into the hands of Robert Hecht in defiance of Turkish laws which vested ownership of antiquities with the state.

|

The Emperor as Philosopher

Image Credit:

Cleveland Museum of Art |

By the late half of 1987, four of these six feet and taller spectacular bronzes, all male, three nude and one wearing a philosopher’s tunic, were known to be in the possession of a Boston coin dealer named Charles S. Lipson. Lipson maintained relationships with several problematic art market actors, not just Hecht but also George Zakos and several others.

The bronzes from Turkey were then circulated by Lipson in temporary exhibitions in several North American museums. From 1967 to 1981 they were displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and Rutgers University. One of Lipson's bronzes, the draped figure relinquished by the Cleveland Museum of Art, was sold to the museum in 1986 via the Edward H. Merrin Gallery for $1,850,000 and quickly dubbed The Emperor as Philosopher, probably Marcus Aurelius.

At the time of sculpture's purchase, the CMA's press releases and follow-up publications openly admitted that the bronze was part of a “group of Roman bronze figures and heads, believed to have come from Turkey” that represented various emperors and empresses, which had been created for a structure honouring the imperial cult in the mid-2nd century. All details which perfectly aligned with the details of the statues which once filled the Sebasteion in Bubon.

Before mandating the statue's seizure, DANY's Antiquities Trafficking Unit, with the assistance of officials from the Republic of Türkiye, were able to locate and interview one of the individuals who actually looted and smuggled this statue and determined that the bronze had been smuggled into Switzerland by Robert Hecht then circulated onward via Charles Lipson, first via the exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and later loaned long term to the Metropolitan Museum of Art via a private collector before ultimately being purchased by the Cleveland museum.

Yet, despite the evidence presented at the time of its seizure and its earlier stance that the object had been lawfully acquired, the museum somewhat lamely cited only the forensic evidence in its late-in-coming decision to relinquish the Marcus Aurelius statue. It indicated that analysis of soil samples taken from within the body of the statue, as well as lead from a plug in its foot used to attach the statue to a plinth, which matched evidence obtained from the Sebasteion in Bubon proving the bronze had once stood there.

While these laboratory findings provide the scientific nail in the coffin, proof linking this beautiful statue to its original site, this testing merely strengthens the preponderance of evidence accumulated in Manhattan's preexisting case for restitution. The evidence of the object's trafficking from Türkiye, didn't rest on scientific analysis, which in this case, was miraculously made possible because the find spot remained relatively undisturbed.

The case was weighted on multiple elements, including the first-hand testimony of farmers who told investigators that men from a nearby village found the bronzes buried on a hillside, beginning in the late 1950s and year by year, working in teams, removed the artefacts from the Sebasteion, many of which were sold to “American Bob,” absence of legal export permits and then unlawfully smuggled out of Türkiye.

Lest we forget, in 1962, the infamous American ancient art dealer Robert "Bob" Hecht was detained in Türkiye after he was seen inspecting ancient coins returning to Istanbul on a flight from heavily plundered Izmir, the same city where the intermediary dealer in this case operated. As a result of that incident, Hecht was declared persona non grata in the country. A friend of notorious Turkish antiquities smugglers, such as Fuat Üzülmez and Edip Telliağaoğlu, Hecht mediated the purchase of a large number of ancient artefacts which were smuggled from Turkey, before he turned his sights on Italy.

To date the ATU has restituted 14 antiquities, valued at almost $80 million, looted from the ancient site of Bubon. This Marcus Aurelius, headless though he be, is the 15th, and one I am sure the citizens of Türkiye will warmly welcome home.

In closing, it will be interesting to see the CMA's own published statement as to why it ultimately elected to close its Federal folly to keep an obviously looted statue in its collection, rather than come to terms with what was already widely known for more than a decade. I suspect they will mention their scholar's “subsequent research,” and her change of heart as to the statue's origins.

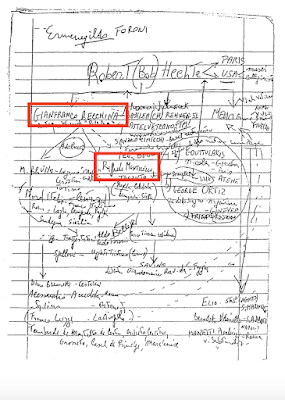

But before they do so, I would remind ARCA's readers that the CMA's now-retired curator, Arielle Kozloff Herrmann, of Shaker Heights, who led the purchase of this Marcus Aurelius bronze in 1986, had longstanding interactions with problematic dealers in the ancient art market. Those include the following, who have repeatedly tied to the illicit antiquities trade:

Robert Hecht, who ravaged Turkey and Italy and who Kozloff thanked for information in the bulletin's acknowledgments on this purchase.

Sicilian Gianfranco Becchina, who she and her husband, John Herrmann, corresponded and met with.

Edoardo Almagià, who currently has an outstanding arrest warrant in New York and who she was introduced to by the problematic Princeton curator, Michael Padgett.

Edward Merrin the dealer who sold this statue to the CMA and whom she later worked with,

Lawrence Fleischman, George Zakos, Brian Tammas Aitken, and Robert Haber.

Look into any of these fellows, most of whom have been featured on ARCA's blog, and then tell me if you think Arielle's latter indecision was unbiased, without motivation, and should have been a deciding factor in the museum's filings against this forfeiture.

By: Lynda Albertson

Caveat Emptor,Christie's,due diligence,Fritz Bürki,giacomo medici,illicit art trade,illicit cultural property,illicit excavation,Ines Jucker,Israel Museum,Ivor Svarc,Maenad,Robert Hecht,Veii,Veio

Caveat Emptor,Christie's,due diligence,Fritz Bürki,giacomo medici,illicit art trade,illicit cultural property,illicit excavation,Ines Jucker,Israel Museum,Ivor Svarc,Maenad,Robert Hecht,Veii,Veio

No comments

No comments

.png)